Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

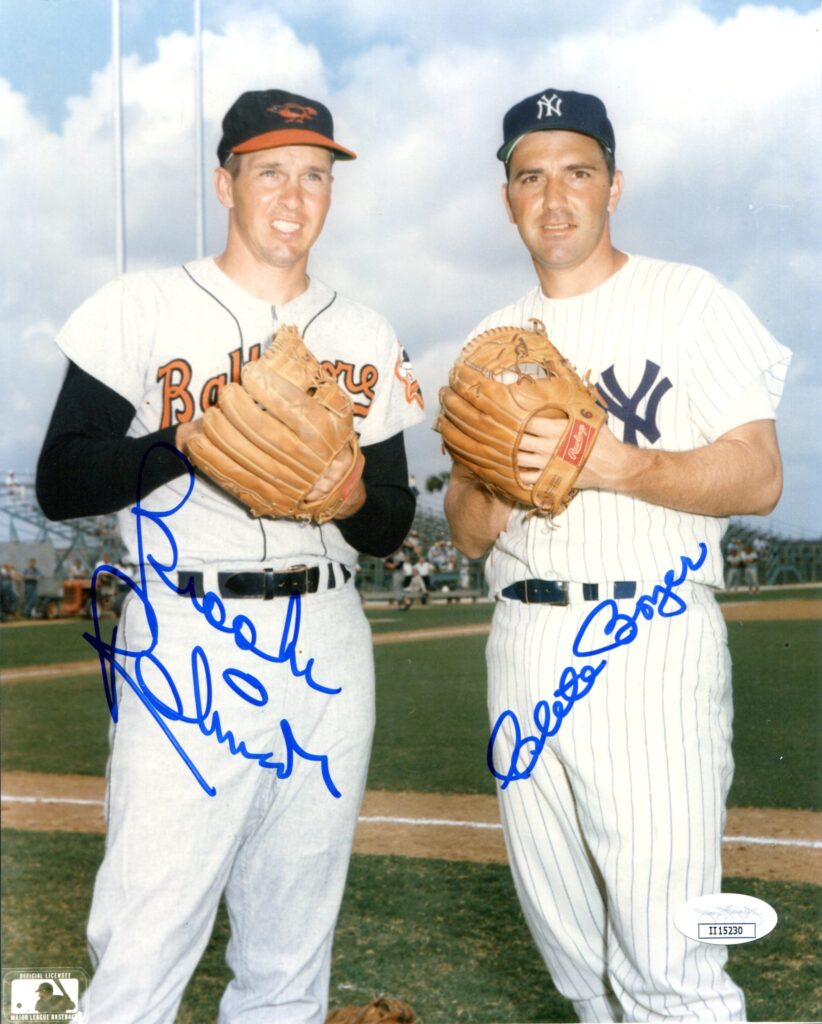

Brooks and Clete Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Today we welcome back Vince Jankoski with another thought-provoking essay, asking the question: Who was a better fielder, Brooks Robinson or Clete Boyer? I’m starting to realize that Vince is a guy after my own heart: He likes to think “outside the box,” and doesn’t necessarily accept the conventional wisdom. And he always does his homework when making his case. Certainly, his essays on Yankee-Kansas City trades fit that description. I know that not everyone will agree with Vince’s conclusions, but I’m glad to give him a forum to voice his well-formed opinions; so I hope you will take the time to read what Vince has to say. Feel free to disagree as forcefully as you’d like. That’s what makes baseball history all so interesting! -GL

Who Was the Better Third Baseman,

Brooks or Clete?

Ken Iglehart of Baltimore Magazine once wrote: “For at least a century, Baltimore has had something of an inferiority complex.” Baltimore is not New York. It is not D.C. It is not even Philadelphia. It is sort of like Detroit on the Chesapeake. Baltimore has crime, poverty, and deteriorating neighborhoods. On the other hand, Baltimore has Edgar Allen Poe, H.L. Mencken, and the best crab cakes inside the Van Allen radiation belt. So, let’s not be too hard on Baltimore.

Baltimore also has Johnny Unitas, Cal Ripken, Jr., and, relevant for present purposes, Brooks Robinson—the three gods of Baltimore sports. Mess with any of these guy’s reputations and you will need to put on your boxing gloves.

Robinson is generally considered the greatest fielding third baseman of all time. Certainly, this opinion runs true in the Charm City. But it is wrong. Robinson was not even the best fielding third baseman of his generation.

By writing this, I understand that I will be chased out of every blue-collar bar in Baltimore. I will be chastised (even ridiculed) by close friends. I live in Maryland. This will be tough on me. But, as Ron Swoboda (a Baltimore native and graduate of Sparrows Point High School) once wrote: You can’t let political correctness stand in the way of the truth. So, here it is: For the years in which both players were in their primes (I choose 1960-1965), Clete Boyer was a better fielder than Brooks Robinson. Please take note of what I am saying. I am not saying that Boyer was a better overall player than Robinson. Certainly, Robinson produced much more offensively than did Boyer. Surely, Robinson had a longer career. Without doubt, Robinson is a Hall of Famer. Also without a doubt, Boyer is not. But for the years under consideration, Boyer was a better fielder.

To prove the point, we need to determine how to evaluate fielding prowess. The most common method is by fielding average. By this measure Robinson outranks Boyer. Robinson’s fielding averages for games at third base only (both players played a handful of games at other positions) were for the years under study .977, .972, .979, .976, .972, and .967. Except for 1965, Boyer’s were lower at .967, .967, .964, .954, .968, and .968. (Statistics are courtesy of baseballreference.com.)

However, fielding averages can be deceptive for two reasons. First, a fielding average depends on the official scorer’s determination of whether to score a play as a hit or an error. Prior to 1980, this function was often performed by beat writers in the home city. Only after 1980 did MLB appoint official scorers. So, the inherently subjective decision to score a hit or an error was compounded by official scorers, consciously or not, favoring the hometown heroes—those that they would need to interview and quote for stories the reporters wrote.

But there is another reason why fielding averages do not determine who is the better fielder. Take two fielders, Fielder A and Fielder B. Ten identical balls are hit to each. Fielder A reaches five, fielding each of them cleanly, and making five outs. The other five balls get past him for hits. Fielder B reaches all ten balls but makes an error on one, making nine outs. Who has the higher fielding average? Not the better fielder, I submit.

Fortunately, there is a wonderful statistic: range factor per game. This stat adds putouts and assists, that is, what you want your third baseman (or any other fielder) to do. Get to batted balls and make outs whether by catching fly balls or by fielding grounders and making the throws to the appropriate base, usually first base. This stat shows the true value of a fielder. Under this metric, for the years under consideration, Boyer is clearly the better fielder. As the following chart reveals, Boyer’s range factor per game was higher for every year except 1960.

Robinson Boyer

1960 3.28 3.24

1961 2.96 3.57

1962 3.10 3.71

1963 3.02 3.36

1964 2.94 3.22

1965 3.10 3.32

So, for example, Boyer’s range factor per game for 1961 and 1962 was .61 higher than Robinson’s. That means for every three games, Boyer gets to two balls and makes two more outs than does Robinson. Go figure how many wins that translates to.

But it gets better than that. As we all know, Boyer was a light hitter. He was often removed for a pinch hitter before the game’s conclusion. So, the more relevant statistic is range factor per nine innings played. Using that metric the difference between Boyer and Robinson is more pronounced. Consider the following chart:

Robinson Boyer

1960 3.32 3.69

1961 2.97 3.78

1962 3.13 3.76

1963 3.07 3.43

1964 2.97 3.31

1965 3.06 3.45

One thing should also be noted. The difference between Robinson’s range per game and his range per nine innings is much less than that of Boyer, reflecting the fact that Boyer was often removed for a pinch hitter. No surprise there.

Boyer is clearly making more outs. In 1961 his range per nine innings is .81 higher than Robinson’s. That means every five games, Boyer makes four outs more than Robinson. And that is the average. Some games Boyer would make two or three outs that Robinson would not. That surely must mean that Boyer contributed to more of his team’s wins than Robinson. The difference for 1962 is .64. Every three games Boyer makes two plays that Robinson misses. Plus, Boyer’s numbers may be understated because of his home ballpark. Before the renovations in the 1970s, Yankee Stadium had a short right-field porch. Opposing teams would load up their lineups with left-handed batters in order to take advantage of the short right-field distances. The opposition’s left-handed batters would tend to hit the ball to the right side of the infield away from Boyer, giving him less opportunity to make putouts and assists. So, who’s the better fielder?

One more thing needs to be mentioned. I have pointed out the above-noted statistics to some fans of Robinson who retort with something like: “I don’t care what the numbers say. I saw Brooks Robinson play. He made plays no one else could make.” I saw Robinson play, too. I also saw Boyer play—scores maybe hundreds of times for both men, both in person and on TV. I was in Riverfront Stadium when Robinson made the play that makes all of the highlight reels of the 1970 World Series. He was playing relatively deep for hard-hitting Lee May, giving him more range. He was in fair territory when he caught the ball. His momentum carried him into foul ground. He bounced the throw to first. Nevertheless, it was an awesome play, one which will be remembered as long as baseball is played. But Boyer made similar plays. He also made more outs than Robinson. He was the better fielder at least during the years of the primes of both men. Robinson won the gold glove in each year, but he was not the better fielder.

While we are speaking of third basemen, why is Robinson’s and Boyer’s contemporary, Eddie Matthews, not mentioned among the greatest third basemen of all time? I may have a few thoughts on that.

Vince jankoski

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with 1.052M hits and over 900 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Information: Excerpts edited from