Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Fred Merkle Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

The Tragedy of Fred Merkle, Part One

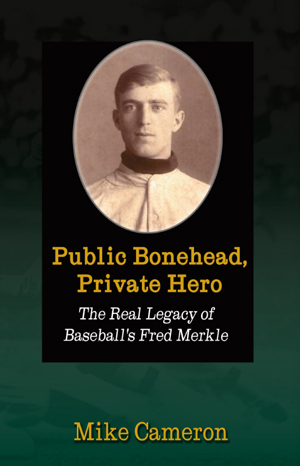

“Strength to overcome adversity…that is the enduring legacy of Fred Merkle’s life.’” –Author Mike Cameron, speaking of Fred Merkle in his book, Public Bonehead, Private Hero, the Real Legacy of Baseball’s Fred Merkle.

As is well-known, on September 23, 1908, New York Giants’ rookie, 19-year old Fred Merkle, committed a baserunning “blunder” in an important game against the Cubs which had bearing on that year’s pennant race. The two teams finished the season tied for first. Beating the Giants in a one-game playoff, the Cubs won the 1908 pennant and also the subsequent World Series against the Tigers. The New York press at the time blamed Fred Merkle for the Giants’ loss, and the game has gone down in baseball lore as the “Merkle Game.”

My late friend Mike Cameron wrote a book about Fred Merkle a few years ago called Public Bonehead, Private Hero. As I got to know Mike over the years, I learned he was passionate about setting the record straight on the infamous Merkle incident and clearing him of wrongdoing. It became his life’s mission. I wrote a review of the book at the time, and I’ve reprinted excerpts here:

In Public Bonehead, Private Hero, author Mike Cameron has written a moving account of perhaps the most infamous game in baseball history in which Fred Merkle failed to touch second base following an apparent game-ending hit. It cost the Giants a victory and possibly the 1908 pennant. With the help of a

vindictive New York media seeking a scapegoat, he was labeled with the cruel epithet “bonehead,” a slander that haunted him for the rest of his life. It inflicted incalculable pain and became a curse continuing through three Merkle generations.

In spite of this handicap, Fred Merkle went on to have a solid 16-season major league career over the years 1907-1926 in which he hit .273 in 1,637 games, amassing 1579 hits, 720 RBI, and 271 stolen bases, including 14 steals of home. From Mike Cameron’s book:

Fred Merkle was a rare power-speed player who usually hit in the clean-up spot, led four teams to pennants, and contributed to two other league championships…Hardly a “bonehead,” legendary sportswriter Grantland Rice described him as ‘one of the most erudite players I ever knew.’

How many people in any walk of life could endure such an enduring slander and still achieve success? Yet Fred Merkle did just that. He retired after baseball to a life of quiet dignity as a devoted husband, father, and successful businessman.

Cameron conveys convincingly his contention that Fred Merkle has been tragically wronged. He includes rare interviews with Fred Merkle’s closest living relatives – daughter Marianne, and family historian and grandniece Sue Baxter – who reveal quite explicitly the pain that the Merkle family has endured even to this day, 112 years later.”

We learn that Fred Merkle spoke two languages, and studied philosophy, history, and advanced algebra. He played the piano and violin, and was considered an expert in both chess and bridge. Giants’ teammate Chief Meyers said Merkle often served as John McGraw’s ‘sounding board.’ McGraw rarely consulted anyone except Merkle on questions of strategy.

Fred Merkle’s failure to touch second base was considered customary at the time. When National League President Harry Pulliam changed the ruling following the eerily similar “Gill Game” of September 4 – a mere three weeks before the Merkle incident – he failed to immediately disseminate his decision to the ballplayers [more on the Gill Game to follow in my next post].

Did you have to touch second base or didn’t you? At the time, it just wasn’t clear. This ambiguity set the stage for the tragic chain of events of which Fred Merkle was the ultimate victim. It was a result that could easily have been avoided; and there was plenty of blame to go round. Many from the baseball world came to Merkle’s defense over the years, including legendary broadcaster Red Barber. Another was Hall-of-Fame umpire Bill Klem:

Johnny Evers talked a great and good umpire, Hank O’Day, into making the rottenest decision in the history of baseball. The intent in this rule [at the time] applied to infield grounders and such. It did not apply to cleanly hit drives to the outfield that make a force-out impossible unless the runner on first drops dead.

On a deeper level, Cameron uncovers the true message of the Fred Merkle tragedy: As long as we maintain our dignity, self-respect, and strength of character, we possess the innate ability to overcome many of life’s adversities. How many of us will ever be challenged the way Fred Merkle was? And yet, somehow, Merkle managed to overcome this injustice. As Cameron writes in the emotional conclusion to his Preface:

‘Strength to overcome adversity…that is the enduring legacy of Fred Merkle’s life.’”

MORE DETAILS ON THE “MERKLE INCIDENT” TO FOLLOW IN MY NEXT TWO POSTS.

Gary Livacari

Information: Excerpts edited from Public Bonehead, Private Hero, by Mike Cameron