Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

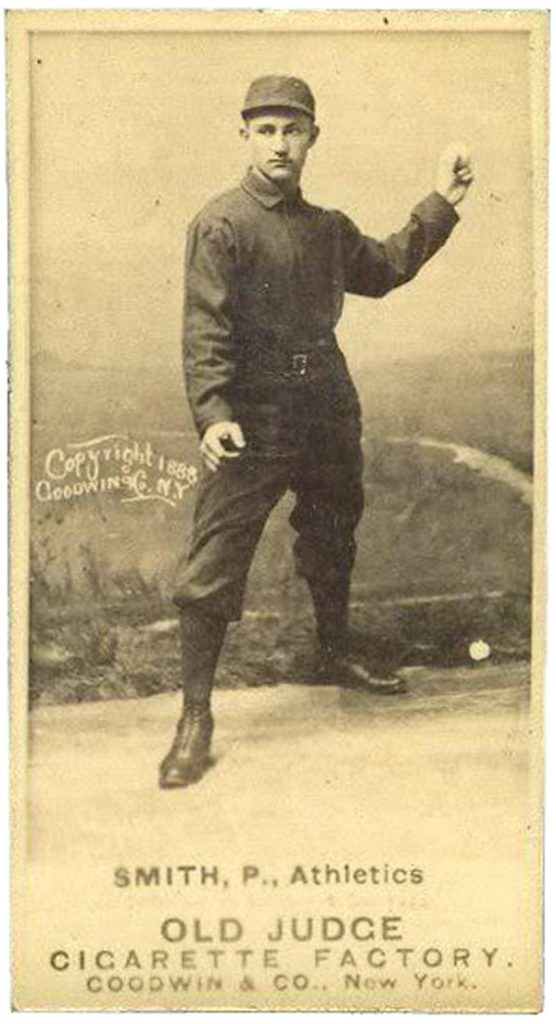

Phenomenal Smith and Other New Hampshire Natives Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

In today’s essay, Paul Doyle returns with an interesting account of one of baseball’s true eccentrics from the nineteenth century, Phenomenal Smith. I think you’ll be surprised when you learn how he acquired his rather, shall we say, unusual nickname. He may have been a character, but he was sharp enough to see something in a young pitcher from Bucknell who went on to become one of the greatest pitchers in the history of the game. -GL

THE “PHENOMENAL” GAME OF BASEBALL

Tip O’ Neil, the late Speaker of the House was famous for his description of how the political world works. “All politics is local,” O’Neil profoundly retorted to a reporter’s question. As a fan of baseball and a student of its history, I’ve always had a similar view of the game, and paraphrased O’Neil’s thoughts with, “All baseball is local.” We all “root, root, root for the home team,” and, as we all know, baseball (or Base Ball as it was originally separately pronounced and written) had its origins in the towns and villages of rural America. If you come from a relatively rural state like I do (New Hampshire), you proudly cheer for those players who were either born where you live or spent a significant time there. You can take pride when you realize those are the players, managers, executives, etc. who have played more than a minor role in the national pastime.

New Hampshire can claim Doc Adams, called by baseball historian John Thorn as one of the “First Fathers” of the game. He was born in the next town over from where I live. There’s a strong debate over whether Adams had more of a role in molding the modern rules that we recognize today, perhaps even more than Alexander Cartwright. In 1858, he was credited with adjusting the distance between the bases to 90 feet. Adams also eliminated the bounce rule, in which a batter was out if a fielder caught the ball on a bounce.

The state has produced a roster of players and managers, including Red Rolfe, Birdie Tebbetts, Stan Williams, Chris Carpenter, Mike Flanagan, and our only Hall-of-Famer, Carleton Fisk (he was born in Bellows Falls, VT, but that was only because the hospital was across the river from the Fisks’ Charlestown, NH home). We can claim many recognizable General Managers including Brian Sabean, Ben Cherington, Neal Huntington, and the new Phillies GM, Sam Fuld.

Recently, I came across an interesting player/manager with an unusual self-appointed nickname. We all remember “Moonlight” Graham who became popular to baseball historians through the movie, “Field of Dreams.” In reading a book on minor league baseball in my state, I came across a reference stating that Moonlight played a couple of years in the old New England League, a class B circuit, that produced many great and good players early in the last century. While perusing Baseball-Reference, I found Moonlight’s stats for 1903 and 1904. He played for local franchises in Manchester and Nashua, and also had a “cup of coffee” in my original hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts. I found nothing spectacular in the statistics for Graham while playing for those clubs, but it was neat to see the connection. What really caught my attention was that the manager of the Manchester nine was listed as Phenomenal Smith.

Talk about clickbait! Who could resist clicking on the link to find out more about someone with that name? Well, it turns out that Phenomenal’s formal name was John Francis, and he was born in Philadelphia in 1864. He pitched in the formative years of professional baseball and had a sub-par record of 54-74 with a 3.89 ERA pitching for both Philadelphia teams, the A’s and Phillies. This was wrapped around quick stints with Baltimore and one appearance for the Brooklyn Grays in the defunct American Association.

Now, here’s the interesting part. Smith bounced around between the minors and the majors in his brief career. He had a breakout season with Newark of the Eastern League in 1885. That year Smith made 18 starts and had a minuscule 0.84 ERA. The pinnacle of his starts occurred in a game against Baltimore that year in which the lefty threw a no-hitter. But it was not just a run-of-the-mill “no-no.” Smith fanned 16 batters and only two batters reached base—a walk and a dropped third strike. Both runners were summarily picked off first. After that game, Smith insisted that he be called “Phenomenal.” Imagine the TV exposure and endorsements if only he was born a century later!

The superlative results in Newark led to a contract with the American Association’s Brooklyn Grays later that year. The legend has it that at one point Smith was so full of himself that when he arrived at his new team, he announced that he was good enough to win games without the help of teammates (Trevor Bauer ancestor?). So you can imagine how the players on that Grays team took to the boastings of a bush leaguer like Smith.

Smith’s career with Brooklyn lasted just that one game. It was helped by the fact that the Grays’ players were interested to see if Mr. Smith could live up to his boast. With the exception of the third baseman Bill McLellan, they let the game proceed almost by “observing” rather than “playing”—dropping popups and letting balls go through their legs. When they did catch the ball, they threw wildly everywhere but to the fielder for the putout. The Grays made14 errors. Shortstop Germany Smith made seven, while catcher Jackie Hayes made Gary Sanchez look like Johnny Bench when he let five passed balls whiz by his catcher’s mitt.

Times were different in 1880’s baseball. Naturally, the paying “cranks” of Brooklyn booed the home team mercilessly, and the Brooklyn Eagle in the next day’s edition let the players have it between the eyes for the “dive” taken by the entire team. Brooklyn club president, Charlie Byrne, called the players to a team meeting the next morning and fined them $500 each, a considerable sum for players mostly making a little over $1500. As for Smith, he was promised another start. But the players were adamant in their refusal to play if he pitched again. Phenomenal had worn out his welcome and soon after was released.

Smith kicked around mostly in the minors until his last major league appearance in 1891 for the Phillies. He was a moderately successful player-manager through 1905, including the end of his career in the Eastern League where he managed the aforementioned Moonlight for two years.

It may be apocryphal, but Smith saw something in a 19-year old pitcher out of Bucknell who was struggling in the Eastern League in the summer of 1899. Despite a 2-13 record for Taunton, Smith signed the young pitcher to a contract for the following summer and mentored him at Norfolk, where he posted a 21-2 record. That put the young player on a path to immortality with the Giants beginning in 1901. The pitcher’s name was Christy Mathewson.

When Smith retired from the Manchester team, he stuck around New Hampshire and finished his career as a police officer for 28 years. He also coached the local college basketball team, St Anselms, in neighboring Goffstown for seven years.

Smith died at the ripe old age of 87 in 1952. In researching this essay, I found that he is buried at St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Bedford, NH. That is only a half-mile from where one of my daughters resides. So, sometime on one of my visits, I may take a detour to pay my respects to another player, who, while not a native, had a long connection to the game and the state where I live. I think discovering local ties to our national pastime is, well, “phenomenal.” Politics and Baseball – joined at the hip!

Paul Doyle

Sources: Baseball-Reference

Schuylkill County Baseball History

Phenomenal Smith Wikipedia Page