Panoramic Photo Above:

Wrigley Field, Chicago

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Today, I’m happy to announce that we will be featuring the first of four installments by Vince Jankoski in his series on “Baseball’s Goats.” Today, Vince starts out with two well-known goats from the Deadball Era, Fred Merkle and Fred Snodgrass. I think you’ll enjoy reading Vince’s account of both of these incidents. -GL

THE GREATEST “GOATS” OF ALL TIME

I was dining in an Indian restaurant the other day when I notice that goat graced the menu. I demurred – instead I ordered an excellent lamb vindalu – but got to thinking about goats.

In contemporary parlance, the term “G.O.A.T” stands for “Greatest of All Time”. ‘Twas not always so. “Goat” formerly meant “goat” as in “the guy who screwed up badly at such a crucial moment as to cost his team a game, a pennant, a season, a World Series, etc. In this respect, a “goat” is defined as a ball player, and is not to be confused with a farm animal or anything else for that matter. While I could not ascertain a “goat” who was truly a “G.O.A.T.”, several “goats” were fairly respectable players who, unfortunately, are remembered for their misplays rather than their careers. Some of the most famous (or infamous) tales of goats are related in the paragraphs that follow.

INSTALLMENT #1: GOATS OF THE DEADBALL ERA.

Goats normally play for good teams. While at first this may seem counterintuitive, in order to be a true goat, the player must miscue at a crucial moment in a crucial game. Bad teams don’t have crucial moments in crucial games. The guy who flubs a play costing his team a seventh place finish is usually forgotten. Furthermore, on such teams and at that point in the season, there have been enough equally memorable mistakes to blend together as one forgettable year. Besides, bad teams are full of goats. They don’t stand out. Correspondingly, goats tend to be fairly respectable players, as one would expect on good teams. Thus, the goats of the dead ball era both come from one of the dominant franchises of the time: the New York Giants. For your consideration:

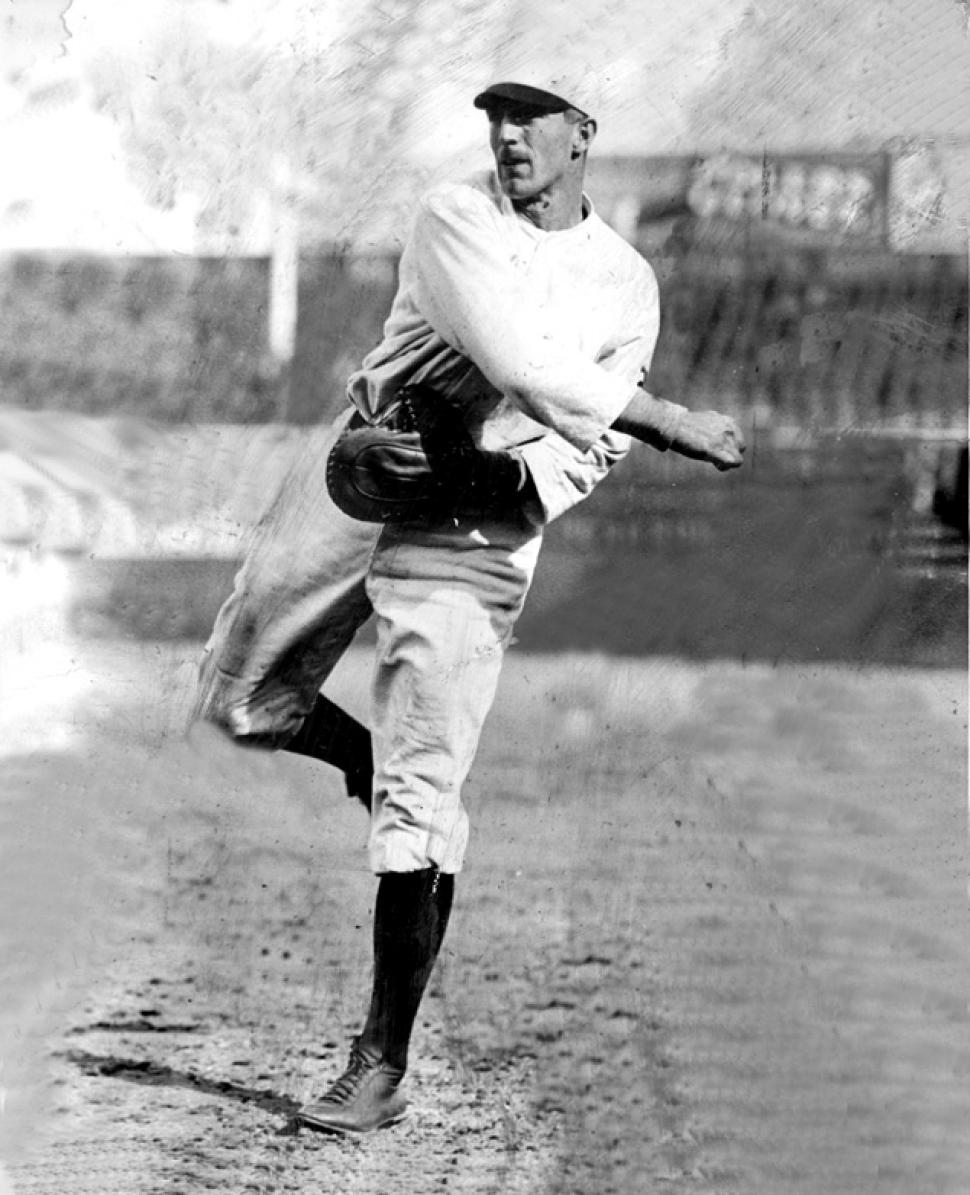

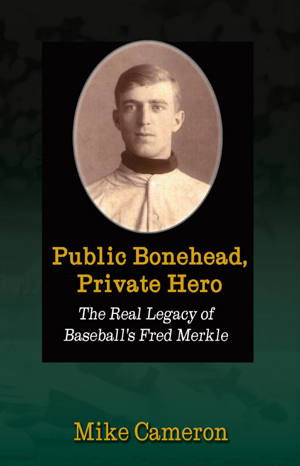

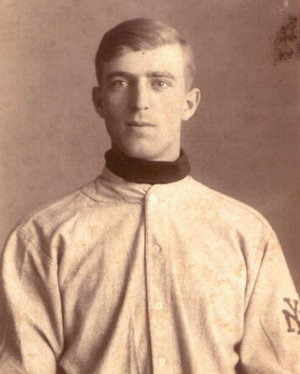

Fred Merkle, the Unfairly Labelled Goat

The earliest “goat” whose story is passed down to the current generation is Fred Merkle. Merkle played first base for 14 major league seasons from 1907-1920 and 1925-1926. In 1908, Merkle at 19 years of age was the youngest player in the National League. He was a seldom-used reserve with the New York Giants who were battling the Chicago Cubs for the pennant that year. One of Merkle’s 49 plate appearances that season occurred on the afternoon of September 23 in New York’s Polo Grounds. The opposition was the Cubs. The Giants held first place over the Cubs by .006. The score was tied at one in the bottom of the ninth inning. With Moose McCormick at first base and two outs, Merkle came to the plate. He singled McCormick to third. The next batter, Al Bridwell, singled home McCormick. However, Merkle, thinking that the game was over once McCormick scored, never touched second base, instead returning directly to the dugout.

Accounts vary as to what happened next. Most recountings state that Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers called for the ball from outfielder Solly Hofman. Some say it was first baseman Frank Chance who retrieved the ball. Some say Evers never got the actual ball, but substituted another ball. In any event, as fans entered the field, confusion reigned. Evers (or Chance) had a ball in his hand and touched second base. The umpires (there were two as per the custom of the time) conferred. Merkle was ruled out. The run was disallowed. With fans storming the field and darkness looming, resumption of play was impossible. The umps ruled the game a tie. National League President Harry Pulliam upheld the umpires’ ruling. Pulliam’s decision was later affirmed by the League Board of Directors.

The Giants and Cubs finished the season with identical 98-55 records. Pittsburg was third, a half-game behind. The tie game would have to be replayed. It was – on October 8, again in the Polo Grounds. This time Mordecai “Three Finger Brown,” pitching in relief for the Cubs, bested Christy Mathewson 4-2. The Cubs won the pennant and the World Series against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers, the last time the Cubbies would win the Series for another 108 years. Merkle’s baserunning mistake cost the Giants the pennant.

Merkle was a competent first baseman. He was a regular for the Giants, Brooklyn, and Cubs for most of his 16 big league seasons. He played on five pennant winners, losing in the World Series each time. He batted .273 for his career with a high of .309 in 1912. But, he forever bore the nickname “Bonehead” for his base running miscue.

In fairness to Merkle, what he did was fairly common at the time. Although at the time the rule was in place that runners crossing the plate do not count where the last out of the inning is a force out, it was often honored in the breach. Merkle did what many others had done, and was blamed for it. The bonehead play, if it was a bonehead play overshadowed a respectable major league career.

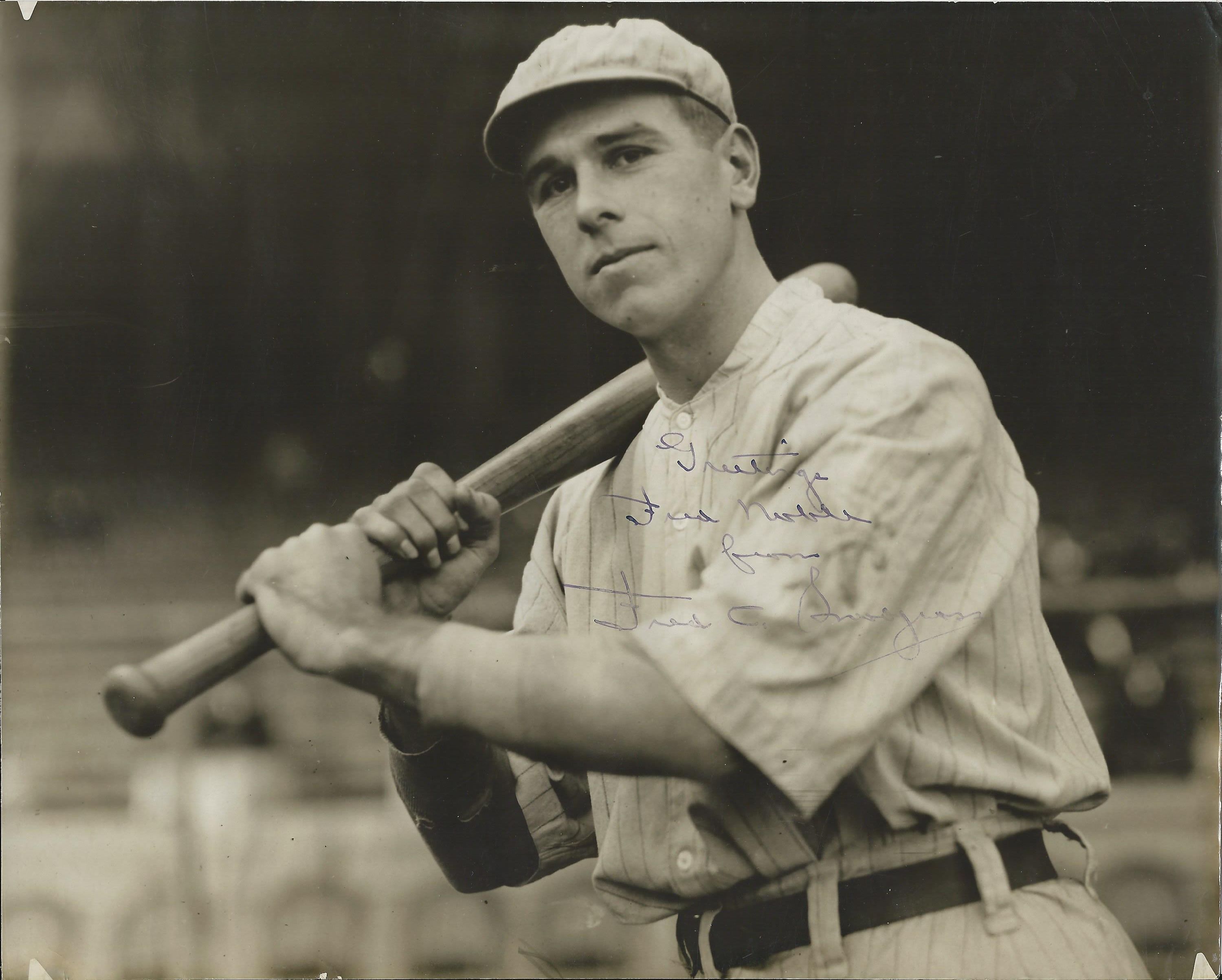

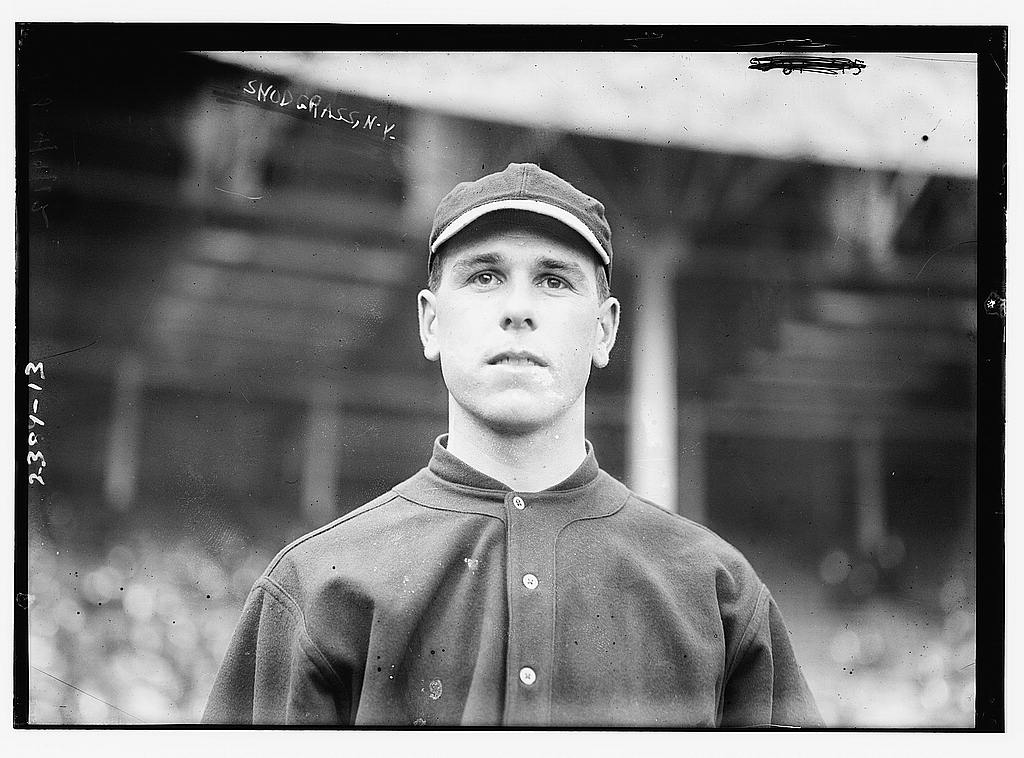

Fred Snodgrass, the Contrite Goat

Fred Snodgrass was a regular center fielder on some great New York Giant teams of the 1910s. He was Merkle’s teammate from 1908-1915. It was in the 1912 World Series against Boston that Snodgrass became a goat. The Series was tied 3-3 with Game Two ending in a tie. The pitching matchup for the deciding game was Christy Mathewson for the Giants and Hugh Bedient for the Red Sox. Bedient was removed for a pinch hitter in the bottom of the seventh inning, and replaced on the mound with Smokey Joe Wood. It was Wood who was the Sox pitcher as the game entered the late innings.

The game was tied at 1-1 after regulation. The Giants scored once in the top of the tenth. In the home half of the tenth, leadoff batter Clyde Engle, pinch hitting for Wood, lofted a routine fly ball to left center. Snodgrass called off left fielder Red Murray, then dropped the ball. Engle reached second base on the error. Snodgrass followed his error by making a spectacular catch on a ball hit by the next batter, Harry Hooper, temporarily saving the game. Steve Yerkes then walked. Tris Speaker singled home Engle, tying the game, with Yerkes advancing to third. After Duffy Lewis was intentionally walked, Larry Gardner hit a game-clinching sacrifice fly. Snodgrass’ error, forever known as “Snodgrass’ Muff” cost the Giants the game and the Series.

Notwithstanding the muff, Snodgrass was a respectable player. He was the Giants’ regular center fielder on three consecutive pennant-winning teams. He, like Merkle, participated in five World Series, losing each time. In his first season as a starter (1910) he hit .321 with 33 stolen bases. He followed that effort by batting .294 with 51 thefts in 1911. That same year he recorded 31 outfield assists. For his career, he batted .275.

After leaving baseball, Snodgrass became a successful banker and politician. He was elected councilman and later mayor of Oxnard, California. His recounting of the muff was as succinct as it was contrite and accurate: “I dropped the darn thing”.

Vince Jankoski

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with over 1,171,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

It’s nice to see “goats” used in the way that is familiar . . . I cannot get used to its current use to denote the “greatest of all time” . . . It was always a treat as a kid when the newspapers would feature the Hero ad the Goat of each World Series game . . .

A fine article. This my favored definition of “goat”. It’s odd how goat has come to mean something completely opposite today. You have to feel sorry for these two Fred’s. Part of baseball’s charm is that its brilliant athletic activity is governed by a plethora of some extremely obscure rules. Kudos to the Cubs’ players who remembered the rule book at such a dramatic moment.

As for Fred the second goat I think he made up for his muff with his sensational catch on the next play.

I think it’s a bit of a stretch to say that Merkle’s mistake cost the Giants the pennant. Remember there were two weeks left in the season when it happened, and all the Giants would have had to do was win only one of the games during that time that they lost and neither the tie nor the replay would have happened. One might also blame McGraw, who to his credit always supported Merkle, for not alerting his team to the potential situation which had occurred in a Pirates game early in September.

Nor did Snodgrass’ error cost the Giants the game or the Series. Of course, an error that let the tying run on base to open the inning is pretty bad, but a case could be made that Merkle and Mathewson really cost them that one. Before Speaker singled in the fateful inning, he lofted a foul pop outside of first, but Fred didn’t make a move for it, some say because Matty kept yelling for catcher Meyers to take it when it was clearly a play for the first sacker. The story goes that, after the foul pop fell untouched, Speaker pointed his bat at Matty on the mound and yelled, ‘You just called for the wrong man, and it’s going to cost you this ball game,’ as indeed it did.