Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive! for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

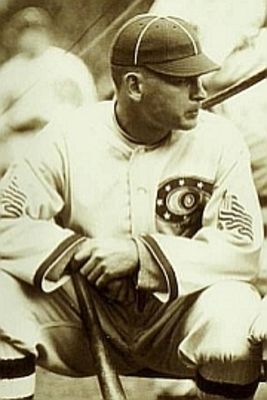

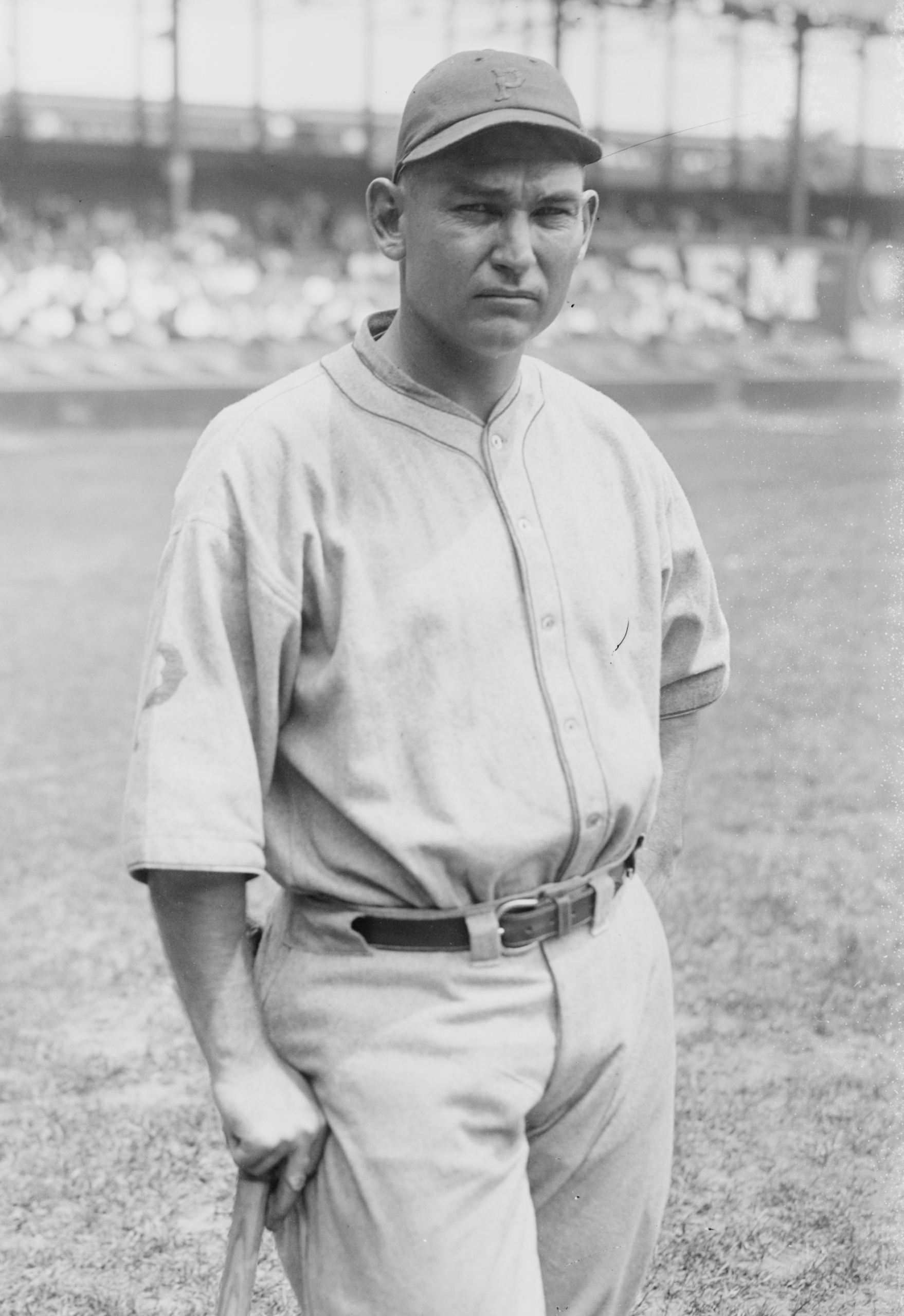

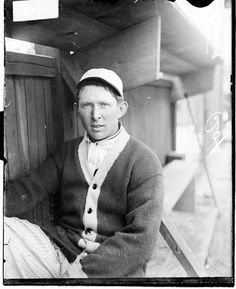

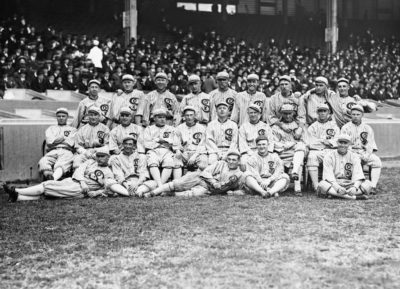

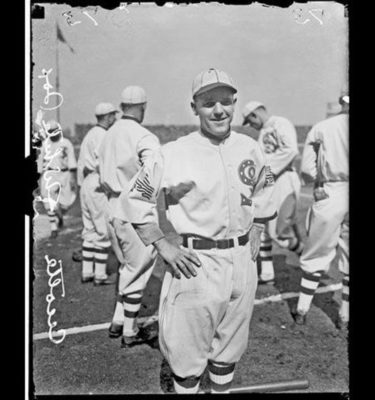

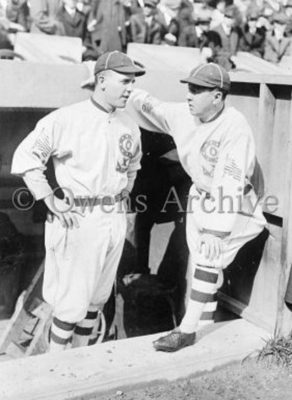

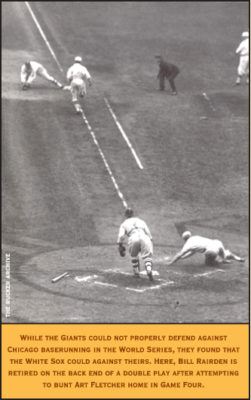

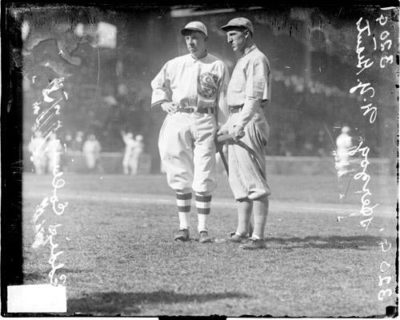

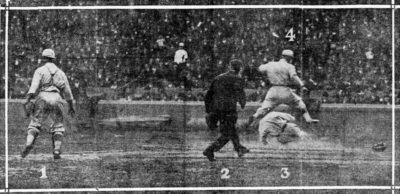

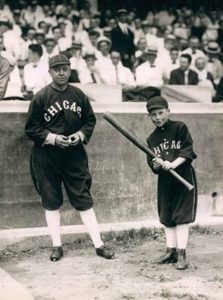

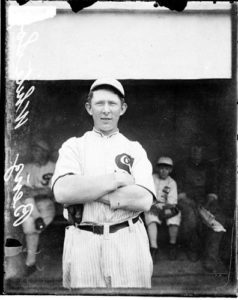

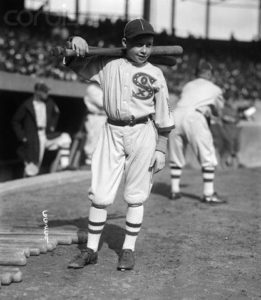

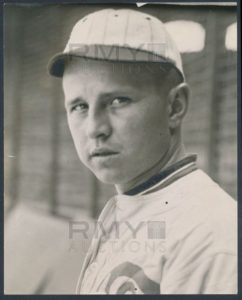

Reb Russell and the 1917 White Sox Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Pitchers Who Converted to Other Positions

“That boy has everything. He has speed, he has curves, he has control, he has nerve, he has strength. What more could I ask for? –White Sox manager Nixey Callihan, speaking of Reb Russell

Some of you will remember my recent essay on Smoky Joe Wood, a star Dead Ball Era pitcher who became a productive outfielder after sustaining an injury and an eventual “dead arm.” Thanks to one of our readers for pointing out another fine pitcher from the Dead Ball Era who also made the switch to the outfield for similar reasons.

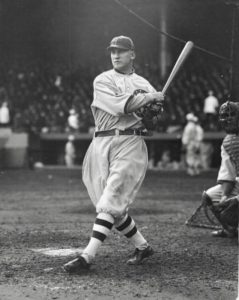

We’ll turn our baseball spotlight today on Ewell “Reb” Russell. A native of Jackson, Mississippi, known for his outstanding control, rising fastball, and coolness under pressure, Russell made his debut with the White Sox on April 18, 1913. The 5’11”, 185-pound lefty put together a spectacular rookie season: 22-16 with a 1.90 ERA, leading the league in games pitched (52), and second in the league in shutouts (8). Mentored by White Sox coach Kid Gleason, he also set a record that still stands with five 1-0 victories, while leading the team in innings pitched (316) and wins (22). It was one of the most impressive rookie seasons in major league history.

Russell suffered through a sophomore jinx season in 1914 (7-12) and was not much better in 1915 (11-10). But in 1916 he was looking good in spring training and was tapped to be the Opening Day starter. He carried his impressive spring into the regular season and compiled a fine 18-11 record, with a league-leading 1.4 bases-on-balls per nine innings, and 0.942 walks-and-hits per innings pitched. His 18 wins led the White Sox staff, as did his 264 innings pitched and five shutouts. Another fine year followed in 1917 (15-5) as the White Sox won the pennant and World Series, defeating John McGraw’s Giants in seven games.

Reb Russell appeared to be on his way to establishing himself as one of the best left-handed pitchers in the game. Comparisons were being made to the American Leagues’ best lefty, Babe Ruth. However, as is so often the case, the injury bug reared its ugly head at the exact wrong time. Arm trouble caused him to tail off to a mediocre 7-5 season in 1918, and he was released in 1919 without appearing in a game. Seemingly on the brink of pitching stardom, just like that he was done, having compiled a seven-year record of 80-59 (.576) with a 2.33 ERA.

But Russell had another arrow in his quiver: he had always been a good hitter. So he accepted his fate and returned to the minors with the goal of reinventing himself as an outfielder and an eventual return to the majors. The plan worked. In 1922, after some solid years in which he established himself as a minor league slugger, he was back in the Big Show, this time with the Pirates. That year he put up some impressive numbers, hitting .368 with 12 home runs, 75 RBIs, and a .423 on-base percentage in 60 games. He tailed off a bit in 1923, but still hit for a respectable .289 average, with nine home runs and 58 RBIs. Despite these stats, his defensive liabilities could not keep him on the roster, and he was released after the 1923 season. Over his two seasons with the Pirates he hit a combined .323; and for his nine-year major league career, .268.

Following his release from the Pirates, Russell was far from finished with professional baseball. He returned to the minor leagues in the American Association (the highest minor league at the time) and became a highly paid star, playing professional baseball through the age of 40. He even posted a .365 batting average at the age of 38 to lead the league.

Reb Russell died on September 30, 1973 aged 84.

Like Smoky Joe Wood, Reb Russell was able to reinvent himself as an outfielder and made a successful return to the majors following arm trouble that ended his days on the mount. As I mentioned in my essay about Steve Dalkowski, it’s too bad Steve didn’t take the same path.

Gary Livacari

Photo Credits: All from Google search

Information: Excerpts edited from Reb Russell Wikipedia page; and SABR biography by Richard Smiley: https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/reb-russell/

Check out my latest book, recently nominated for the SABR 2020 Lawrence Ritter award: Reflections On the 1919 Black Sox: Time to Take Another Look now available on Amazon in e-book and paperback. All profits go to the Illinois Veterans Foundation

Vote In Our New Poll: How Do You Feel About New Rules Changes?https://wp.me/p7a04E-7Ov

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. Click here to view Amazon’s privacy policy

Interesting, Gary, that Reb Russell established himself as an outstanding major league pitcher in the Dead Ball Era, and then made a nice comeback as a hitter when the lively ball was introduced.

Thanks again for enlightening us with another fine essay that ventures into the archives of the great game of baseball.

Best, Bill

Another thought-provoking and informative profile, Gary. Many thanks.

In identifying successful pitchers who “reinvented themselves” as productive hitters later in their careers one tends to think of guys like Joe Wood, whom you featured previously; of course The Mighty Babe (who never really lost it as a pitcher), or Stan Musial and Rick Ankiel, among others. (I also remember Bob Lemon and Hal Jeffcoat, for example, but those two went from the outfield to the mound instead.)

With your portrait of Reb Russell, though, you have pulled a fascinating professional history out of the primordial ooze. I had no clue, although I daresay that Germany, whose own life began to blossom in the Dead Ball era too, was intimately acquainted with him back in the day.

It’s pretty amazing how fragile, and hence excruciatingly fleeting, the magnificent skills of some of the most dominating athletes in major-league sports can be. One minute they have the world by the tail; the next they’re clinging to a tiger for dear life. Steve Blass had it until he didn’t; Steve Sax suddenly couldn’t hit Tiny Bonham with a thirty-foot lob; Karl Spooner was perfectly positioned to be the first Sandy Koufax; and countless others went from MVP-caliber careers to wistful dreams of might-have-beens in a virtual blink. They all make for intriguing stories, and your account of Mr. Russell’s life and times is a perfect if previously little-known example.

Many thanks again, Gary, for enlightening those of us born in the era of the Lively Ball. Who’s up next?

Two that I can think of who started out as pitchers and had a short career pitching and became star position players were Lefty ‘O’Doul and George Sisler.

Thanks to the always provocative Dr. Keedy for more wit and wisdom. Although his reference to me was probably only discerned by me.

“Stan The Man” was always a huge favorite of mine, the way he perfectly covered the plate and uncoiled into a pitched baseball. But he was hardly a successful-pitcher- turned-slugger. He was signed by the Cardinals in 1938 as a pitcher, but was often injured and erratic on the mound, in the minor leagues. It was strongly suggested he play the outfield everyday when he was called up by St. Louis in ’41.

Musial had a monster year in 1948, missing the Triple Crown by one home run: 39 four baggers behind Mize and Kiner’s 40.

There were always rumors he had one homer washed away by a rain out that would have done the trick, but this was never substantiated even by painstaking research.

However, Musial did have 429 total bases that year, the most by any hitter in 75 years. And his 251 on the road in ’48, “busted Lou Gehrig’s record by a base.”

Stan The Man has the distinction of racking up more career four-baggers than anyone else who never hit forty in a single season. Unlike Mize and Kiner (and Joltin’ Joe Dimaggio, for that matter), he actually went deep more often than The Great Gil, whom Stan referred to as “the greatest first baseman of his generation.”

How’s that for “convoluted,” Dr. S?

–What was the topic?

When you were absent from the ranks of the bloggers for a spell, Michael, I was concerned and hoped everything was OK. I wished your distinctive replies would once again appear.

What do they say–be careful what you wish for? (Ha! Ha!)

Germany/Bill