Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

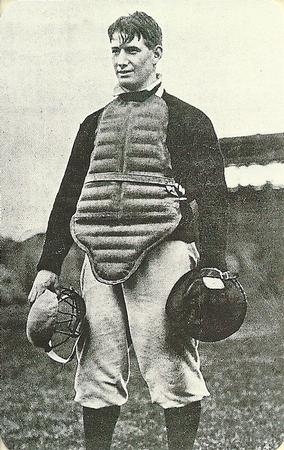

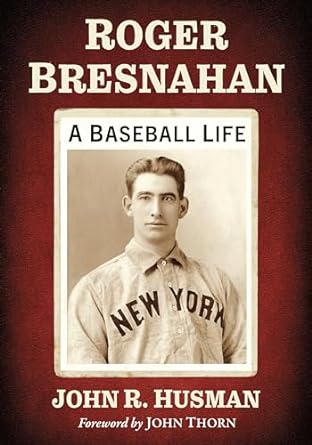

Roger Bresnahan, A Baseball Life

by John R. Husman

Reviewed by

Gary Livacari

If you asked most baseball history students what they know about Roger Bresnahan, you would likely hear something like this:

“Isn’t he the guy who invented shin guards? Isn’t that the reason he’s in the Hall of Fame?”

And to be honest, that was about the extent of my knowledge. After reading the book, Roger Bresnahan, A Baseball Life, by John R. Husman (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2024), I’m now fully aware that there was a lot more to Roger Bresnahan’s career than just the shin guard story, as important as it was to the game. Besides transforming the catching position — dramatically decreasing potential injuries to the thousands of backstops who came after him — he was an outstanding ball player, an indispensable team leader, and was widely recognized as the greatest catcher of the Deadball Era.

Roger Bresnahan was certainly one of the most versatile players in the game’s history. Starting his career as a pitcher, he eventually played every position on the diamond — and played them well. Readers will be surprised to learn that of his 1447 major league games, only 972 were behind the plate and included 232 games as a centerfielder. The remainding 243 games were scattered among every other position in the infield and outfield. In addition, he possessed speed with 232 stolen bases, was highly regarded as a clutch hitter, often batted leadoff, and repeatedly played through injuries that would have debilitated many other players. In one memorable game played on April 28, 1903, he hit a double, an over-the-fence grand slam, stole a base, and scored two runs. It would be 112 years before another Giant catcher would hit a grand slam and steal a base in the same game.

This passage demonstrates Roger Bresnahan’s aggressive on-field persona and his approach to the game:

“Roger was extremely competitive, stubborn, confident, fearless, hardnosed, and willing to do almost anything to gain an edge in order to win. The esteemed baseball scholar Bill James described him: ‘A short 200-pounder, who was fast and strong and agile and aggressive’…Almost every paragraph written about him seemed to include the adjective ‘fiery.’ He brimmed with ambition as he yearned to manage and own a team at a very young age…” (1)

With over a quarter of Deadball Era players of Irish descent – and hoping to increase his own “Irishness,” – Bresnahan faked his June 11, 1879 birthplace as being Tralee, Ireland; whereas it was really Toledo, Ohio. Hence the origin of his nickname, “The Duke of Tralee.” Over his 17-year major league career, Roger hit .279, with 71 home runs, 530 RBIs, a .386 on-base percentage, and a remarkable 126 OPS+. His career statistics may seem modest to us, and we wonder how these numbers landed him in Cooperstown. For those of us viewing the game from our twenty-first-century perspective, it’s hard for us to perceive the value of a hardnosed catcher during the Deadball Era when tough catchers were considered more important to the team than pitchers. This point is made clear in the Foreword by baseball historian, John Thorn:

“What made for stardom in that perhaps simpler time was not mere proficiency but courage — steadiness, endurance, bravery…character…Playing the position steadily, day after day, was more important to a team than what a catcher could do with the bat. King Kelly and Ewing — and, more recently Deacon White — would not have won their Hall of Fame plaques without their batting lines, but the weak-hitting [catchers] — like Frank Flint, Bill Bergan, Chief Zimmer, Doug Allison, and Lou Criger — might be better appreciated if modern eyes could see them as their peers did.” (2)

The author traces Bresanhan’s career which began as an 18-year-old pitcher debuting with the Washington Senators on August 27, 1897. After a season with the Chicago Orphans in 1901, he was recommended as a pitcher by Chicago manager, Clark Griffith, to John McGraw, then the manager of the Baltimore Orioles in the new American League. He soon proved his mettle to his manager, as perhaps McGraw saw a personification of himself in the young ball player’s aggressive style of play. The baseball world was shocked on July 8, 1902, when McGraw abruptly departed Baltimore in midseason to become manager of the New York Giants. Roger was one of four players — along with Jack Cronnin, Joe McGinnity, and Dan McGann — McGraw took with him to New York. It was a move that proved to be immensely successful for all involved. With McGraw as his mentor, he learned the vitriolic, sometimes violent, umpire-baiting, win-at-all-costs style of his famed manager, characteristics that stayed with him for the remainder of his career. Not surprisingly, he was ejected 30 times, a number surpassed by only five other players.

While in New York, Roger had a breakout year in 1903, hitting .350, after a season-long battle with Honus Wagner for the title. New York sportswriters now regarded him as “one of the best ball players in the US.” He followed this with an injury-filled .284 season in 1904, and then rebounded to hit .302 in 1905. In the 1905 Fall Classic, he caught every inning of the five-game series, including all three of Christy Mathewson’s shutouts, commencing a life-long friendship with the great pitcher. He was the hitting star of the World Series, posting a .313 average, along with a .500 on-base percentage. By the season’s end, New York fans worshipped their budding young star. Newspaper accounts were referring to him as the “best living catcher.” No less an authority than Mathewson referred to Roger as the most important factor in the Giants’ success during his years with the team.

Roger Bresnahan epitomized toughness, enduring an assortment of injuries during his career that would have sidelined many other players. Almost every other page of the book detailed injuries to either his often-mangled fingers, or to his shins, his chest, and even his head. Calling to mind the fatal injury to Ray Chapman in 1920, he suffered a horrific beaning on June 18, 1907, and lay unconscious on the field for over 30 minutes. The force of the blow propelled the ball to the first baseman who caught it on the fly. A priest was called who administered the Last Rights of the Catholic Church. When told that his great catcher would probably die, a sobbing John McGraw expressed Bresnahan’s value to the team:

“He was the best ball player in America. He could play anywhere. He always played honestly, and he put more heart into the team when luck went bad than any man I ever knew. Bresnahan could no more be replaced upon the New York team than you could replace a victorious general in an army. I’m not much on praying, but tonight, I pray with all my heart that he gets well.” (3)

When he returned to the lineup on July 12, a mere three weeks later, Roger responded with two singles and a stolen base. Playing centerfield, he made two difficult catches. He was back behind the plate again on July 23 and caught every game through mid-September, including one stretch of eight straight days, a 13-inning game, and five doubleheaders.

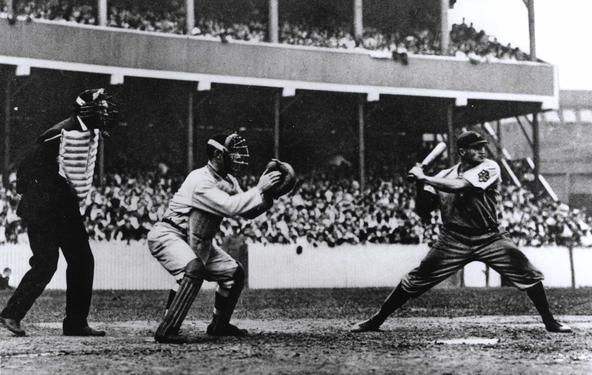

Of course, Bresnahan is mostly remembered for being the innovative catcher to first utilize shin guards, which he debuted on Opening Day, 1907. As described by the New York Daily Tribune, “Bresnahan…caused considerable amusement by wearing long shin guards similar to those worn by cricket players.” Noteworthy is that Roger never claimed to be the inventor, saying he got the idea from Phillies’ catcher, Red Dooin. As the author points out, there was a major difference between Roger’s shin guards compared to other versions that had come before him:

“They were designed for baseball and substantial which meant that could not be hidden under clothing, Because of their design they proved to be successful and because they were first worn by Roger, they soon became universal because he paved the way by absorbing the initial mockery, hazing, and taunting which he had predicted…What Roger Bresnahan did on Opening Day in 1907 had a permanent effect on the game and saved countless injuries and missed play. Roger said amid all the objections and ridicule directed at him, ‘I ought to have a Red Cross or Carnegie medal for introducing something that will keep catchers out of the hospital’.” (4)

Bresnahan always desired to manage, and in 1909 McGraw, never one to stand in the way of a player’s advancement, reluctantly allowed him to join the Cardinals as player/manager. In the process, he lost the “backbone” of the Giants. Arriving in St. Louis, he brought with him the McGraw spirit and worked his players hard in preparation for the upcoming season. We learn of his up-and-down relationship with Cardinals’ owner, Helene Britton. Following his initial success in revamping the last-place Cardinals — at one point he was called the most popular man in St. Louis — he fell out of favor with “Lady B” over a proposed trade to Cincinnati of favorite Miller Huggins. She eventually released him with three years remaining on his contract. After a lengthy and bitter dispute over a profit-sharing clause, a settlement was reached. His next stop was an unfortunate one in Chicago, where he became a “$12,000 coach” for the Cubs’ volatile owner Charles Murphy. It was another situation which did not end well.

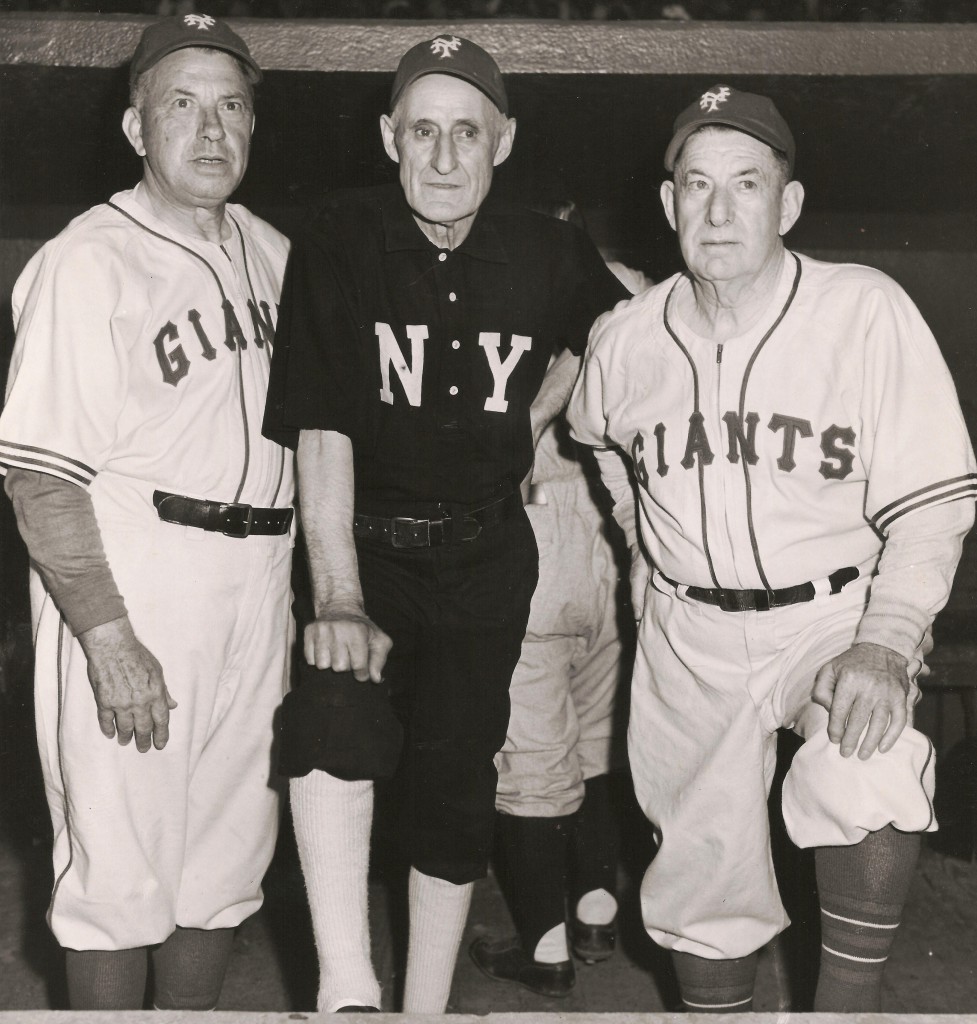

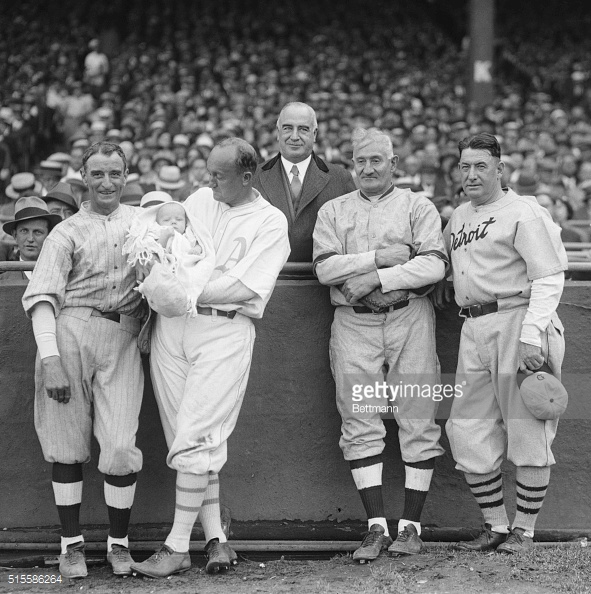

Following his release, he eventually fulfilled another life-long ambition as he became part owner of his hometown Toledo Mud Hens (1916-1923) where he worked tirelessly to improve the fortunes of the team. As the author notes, “His time was marked by frustration, financial stresses, and losses in the field.” Then followed years back in New York as a Giants coach. The stock market crash of 1929 hit him hard and he lost virtually all his possessions and wealth. Roger took on numerous odd jobs and even had a failed venture into politics as he and his second wife, Toledo-native Gertrude Norenberg, faced years of financial difficulty. Finally, the position of pitching coach for the Detroit Tigers gave him some security. His last appearance in uniform was at the War Bonds game, played on August 26, 1943 at the Polo Grounds. He was the catcher when Babe Ruth stepped to the plate against Walter Johnson and hit the ball into the right field stands.

It’s always difficult to compare ball players from different eras, but the author makes a valiant effort comparing Roger Bresnahan to Johnny Bench. There are some surprising similarities. Both played for 17 seasons posting an identical 126 OPS+. Bench’s batting average was .267 (13 points above his league’s average), while Roger’s was .279 (plus 23). Of course, Bench holds a huge lead in home runs (389 to 26), but as the author points out, “Nobody that played during the Deadball Era hit home runs at Bench’s rate.” Also noteworthy is that Roger stole 212 bases — the highest ever for a player whose primary position was catcher — while Johnny swiped just 68. All this is not to say that Roger Bresnahan was the equal of Johnny Bench, but only to point out that Roger, like Bench, was the most dominant catcher in the era in which he played.

Does Roger Bresnahan deserve his place in the Hall of Fame? Interestingly, two books that analyze the worthiness of Hall of Fame members (The Cooperstown Casebook, by Jay Jaffe; and The Baseball Hall of Fame Corrected, by Eddie Daniels) both conclude he is deserving of his spot. While not possessing the slugging statistics of many Hall of Famers, Bresnahan possessed many of the intangible factors needed for inclusion:

“Voting shall be based upon the player’s record, playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the teams on which the player played.” (5)

For those still not convinced, perhaps this reflection from the great Honus Wagner, who observed Roger as an opponent for 15 years, will help sway opinions:

“Supposing we were choosing up sides for two all-time baseball teams and I had the first pick. I wouldn’t have to look far because the first man I’d select would be Roge. Here’s why: He could do anything. He could catch, play the infield, or play the outfield. He could hit, throw, and run. I’d say he was the most talented and versatile player in the history of the sport. (6)

Or this from Christy Mathewson:

“He was as brainy as he was tough. He was a leader on the field, always coaxing the other players while holding the team together through tough times.” (7)

In spite of the length of this review, I’ve barely scratched the surface of all that’s covered in Roger Bresnahan, A Baseball Life. Many details were provided to the author from the scrapbook of grandnephew, Roger M. Bresnahan. Long overdue, it’s virtually the only detailed look into the career of this underappreciated Hall of Famer. It belongs in the library of all serious students of baseball history, as it goes a long way to enhance our understanding of the valuable role played by catchers in the early decades of twentieth-century baseball. The book is well-written, well-edited, and heavily sourced. John Husman’s extensive research, which he compiled over many years, is to be commended. I enjoyed the author’s engaging writing style which held my attention from the first page to the last. Readers will also enjoy, as I did, the many direct quotes from early twentieth-century sportswriters exhibiting the expressive writing style so prevalent in that era.

After reading it, there’s no doubt in my mind that Roger Bresnahan has been sadly overlooked by baseball historians and is more than deserving of his plaque in the Hall of Fame. Roger Bresnahan passed away on December 4, 1944, aged 65, in his hometown of Toledo, Ohio. He was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.

Gary Livacari

Footnotes:

(1) Roger Bresnahan, A Baseball Life, by John H. Husman (McFarland & Company, 2024), p. 217

(2) ibid. p. 2

(3) ibid. p. 88

(4) ibid. p. 83

(5) ibid. p.236

(6) ibid. p. 237

(7) ibid. p. 215

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1500 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with over 1,201,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Nice one. Thanks, Gary