Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

1943 Phillies Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Paul Doyle picks up on my recent tribute to Hall-of-Fame manager Bucky Harris and gives us an interesting account of an incident I was not familiar with. It involves Harris and short-tenured Phillies’ owner William Cox from 1943. This proves that just when you think you “know it all,” something else pops up to show you that you have a lot more to learn. Anyway, I think you’ll enjoy what Paul shares with us today, which I’ve given the subtitle: “You Bet!” –GL

“Owners Aren’t Angels”: The Story of the 1943 Phillies

(Subtitle: You Bet!!)

“If there is a ‘jerk’ connected with the Phillies, it is William D. Cox, president of the baseball club…and he’s an all-American jerk!” -Bucky Harris, to the Philadelphia Inquirer, August 3, 1943

Gary Livacari’s recent essay on the Washington Senators’ legendary “Boy Wonder” Bucky Harris highlighted the wonderful career of the Hall-of-Fame manager. Most remember his tenures with the Senators, Yankees, and Tigers. But one of the more unusual stories from his career involved his brief time with the Philadelphia Phillies. It was brought to light in a recent column by Matt Gelb in the online site, The Athletic.

The story combines the intriguing elements of a self-indulgent owner, gambling rumors, and a hurried ownership change. It all happened decades before Charlie Finley, George Steinbrenner, Pete Rose, and Marge Schott arrived on the scene. As if that wasn’t enough, the story also includes rumors of Bill Veeck’s attempt to buy the Phillies and field an all-black team—four years before Jackie Robinson’s historic shattering of baseball’s color barrier.

The saga begins in 1942 with the prior owner of the Phillies, Gerry Nugent, one of the worst stewards of a major league club in history. His team won a whopping 42 games to go along with 109 losses that year. Going back to 1918, the Phillies had only one winning season and were the worst team in the National League for over two decades. Nugent’s stewardship certainly didn’t help that dismal record.

The club was deeply in debt and owed the league over $125,000 from prior loans. Plus, they were in-the-hole for at least another fifty grand to other creditors. With no assurances that Nugent would change things soon, the league took over the team at the end of the 1942 season and immediately sought new ownership.

A somewhat discredited story suggested that baseball maverick Bill Veeck had discussions that off-season with a group of investors to buy the team. He was simultaneously making arrangements with Abe Saperstein, owner of the Harlem Globetrotters, to act as an agent to sign Negro League stars. The Negro Leaguers would hold their own training camp, while the start of the Phillies’ camp would commence with players already on the roster.

Veeck was rumored to have plans to release his entire Phillies squad at the end of camp and start the season with the Negro League players. This story was detailed in Veeck’s 1962 autobiography Veeck as in Wreck. Baseball historians have debated over just how far along Veeck was with his plan.

The story was the topic of a scathing article in a 1998 SABR national publication that disputed Veeck’s assertions. Eight years later, baseball historian Jules Tygiel wrote a follow-up essay in the same publication. He provided at least partial validity to Veeck’s versions, albeit the plan was not as fleshed out as Veeck had insisted for years.

Nevertheless, the league was proactively seeking a buyer before the start of the 1943 season. Bids were taken under advisement, and, after due diligence, a group led by lumber magnate, William D. Cox, was designated the new owners of the club. To add to the melodrama, this group beat out another group led by John Kelly, the father of future actress and princess, Grace Kelly.

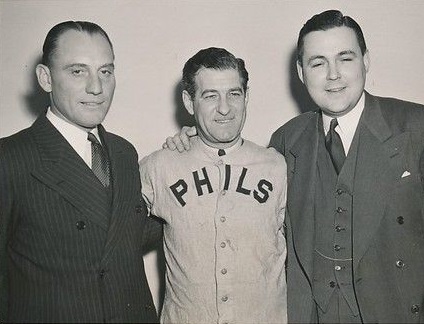

(In the featured photo, we see in happier days manager Bucky Harris in center with star Chuck Klein on left and Phillies owner William Cox on right).

Cox was, to be charitable, a “hands-on” owner. He played college baseball at Yale and thought of himself as someone who knew more about the game than the baseball people running the club or even those he hired. To make a splash, he

threw out names he was considering for the manager’s job. They included Bucky Harris and Bill Dickey, among others. The problem with Dickey was that he was still an active player. This elicited claims of tampering from the Yankees, and a war between Cox and the New York press ensued. Eventually, he chose Harris, but little did he realize that the move would ultimately lead to his demise.

To show just how arrogant he was, Cox thought nothing of dressing in uniform and taking batting practice with the club. He offered advice to individual players, often contradicting coaches. He even fought with umpires. Baseball lifer Bucky Harris was livid that an owner would actually go around him and undermine his relationship with his players, leading to dissension in the clubhouse.

Nonetheless, under Harris’s leadership, the sad-sack team was playing over .500 as the mid-point of the season approached. Unfortunately, the Phillies’ water soon found its natural level in July as they lost 24 of the next 35. This led Cox to announce to some reporters that he had fired Harris and hired Freddie Fitzsimmons to replace him. Except for one minor issue: He forgot to tell Harris. Not surprisingly, all hell broke loose when a reporter called Harris with the news. Visibly upset, he responded that he knew nothing about it.

The news also upset the Philadelphia players, as they considered it a bush league move by a bush league owner. The enraged squad signed a petition with a threat to strike. The next day, as start-time approached, they refused to dress for the game. Harris then appeared in the clubhouse to inform the players that he was satisfied with an apology Cox had extended. The crisis was temporarily averted, but it was far from settled. Cox and Harris used the press to bicker back-and-forth until Harris issued a scathing statement which included the above quote a few days later.

Cox was still sensitive to the beratings of the New York press. During the July swoon, he had made a statement that he had “bet” his team would still finish much higher than the basement-dwelling teams of the past. Was he speaking figuratively, or did he mean it literally?

According to The Athletic, Harris, with extensive contacts throughout the league, worked baseball’s “back channels” following his dismissal. He subsequently met with Commissioner Landis and an investigation was opened on Cox’s gambling. As the season rolled on to its conclusion, Cox was evasive with the investigation and was not forthcoming with details of his “bets.”

Landis, as is well known, did not suffer fools gladly. He banned Cox for life in late November. Cox appealed and was granted a public hearing the following month. In his testimony, Cox downplayed his betting, contending they were simply friendly bets with associates. Later in his testimony, he concocted a wild story that he placed bets to test a disloyal club official. Meanwhile, another club official testified that Cox told him he had made money betting on the Phillies. As Matt Gelb wrote in his article:

The hearing ended with Harris’ testimony. He (Harris) had made a trip to New York…with a team employee earlier in the season. The owner’s secretary, Miss Massie, had placed a call while the two men waited. She asked for the odds on that day’s game. Harris was confused. “What were the odds?” he asked. “13-5 Brooklyn,” she said, forever altering the course of the franchise. “Do you mean to tell me,” Harris said, “that Mr. Cox is betting on baseball?” “I thought you knew that,” she said. “I have to keep a book on that.” Landis stood his ground and Cox’s “banned for life” became a reality.

Over the off-season, new ownership was again sought. Bill Carpenter was named president of the club, which lead to a 37-year stewardship by the Carpenter family. Cox’s 276-day whirlwind ownership of the Phillies was over. Bucky Harris would go on to manage the Yankees to a World Series championship four years later on his way to the Hall of Fame.

It’s more than a bit ironic that baseball’s stance on gambling has undergone a 180-degree change, now forming partnerships with legal sportsbooks. Lesson learned? Hardly. I have a feeling Judge Landis would be rolling in his grave.

Paul Doyle

Sources: Matt Gelb, “The Athletic” – “The ‘Jerks’ Demise” (-February 15, 2021); Jerome Holtzman, Baseball Digest-August 2004; Jules Tygiel, The National Pastime-2006 (SABR).