Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Perfect Games Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

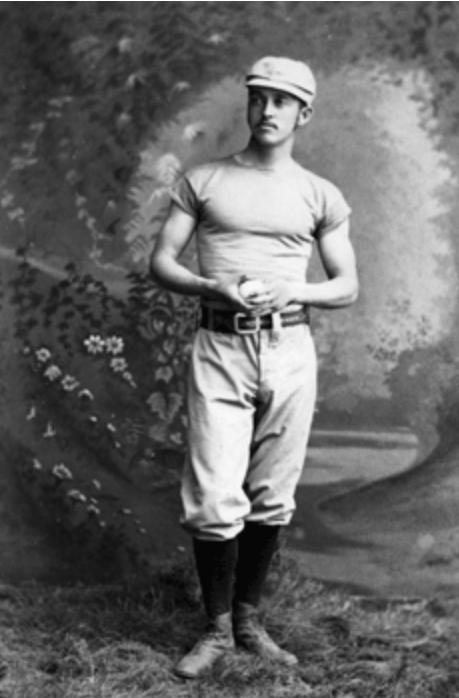

I’ve seen the photo of the skinny,19th-century ballplayer in the funny-looking uniform before, but now I know who he is. Thanks to Paul Doyle’s interesting essay today, we learn about the first Perfect Game in baseball history and the pre-med student who threw it.

By the way, check out the photo gallery to see pics of all 23 pitchers of “Perfect Games”! -GL

NOBODY’S PERFECT:

The Story Behind Baseball’s First Perfect Game

These last few baseball seasons have been puzzling to long-time baseball fans who have been barraged by analytical terms such as launch angles, exit velocities, spin rates, and other terms that warm the heart of physics majors, if not baseball fans.

The resulting acceptance of these theories of “winning baseball” has been exacerbated by the short season of 2020 and the lack of offense and the almost record-breaking number of no-hitters thrown by pitchers in the early stages of the 2021 season. With six being thrown through the middle of May, a once rare feat has almost become mundane. Someone uttered after the sixth that it would take a perfect game to catch the baseball aficionado’s attention.

After all, there have only been 23 of them thrown in the 145-year history of the game, while there have been a total of 311 no-hitters including this year (288 non-perfect).

With the anniversary of the first perfect game coming up on the horizon on June 12th, it’s a good time to reflect on the first one thrown in a major league game by Lee Richmond in 1880 in Worcester, Massachusetts.

It is interesting in researching this event that the term “perfect game” was not a part of the vernacular until far into the future. We also know that the pre-modern era of the game that existed was a far different version. There was no pitcher’s mound that existed. Pitchers threw from a “box” that was only 45 feet from the batter (it would be changed to 50 feet the following year and stay that way until 1893 when the box changed to a mound and the distance to 60 feet that became 60 feet, 6 inches because of an incorrect measurement).

However, the game that day was played at Worcester’s home field, Driving Park, which was located on the grounds of the city’s Agricultural Fairgrounds. Richmond at the time was a student at Brown University in Providence, RI, who usually commuted to the Worcester Ruby Legs home games by train. He needed the salary to help pay for his tuition at Brown. He was one of the highest-paid in the league at $2,400.

In a recent article in the Boston Globe, Kevin Dupont revealed that Richmond, who was about to graduate from Brown, attended an all-night celebration with his classmates the night before. In fact, it appears that Richmond played a baseball game at 5 o’clock that morning as part of the celebration, and according to Dupont, “…turning in at approximately 6:30 AM. After a brief snooze, he was up to catch the 11:30 train to Worcester, and by dusk, he was in the baseball history books.”

The southpaw hurler had a 32-32 record with the Worcester club that year. He started 66 games for the Ruby Legs, pitched in 8 others in relief with a mind-boggling 590 2/3 innings in that campaign. The team played a total of 83 games that year.

As to the game, it was a crisp 1:26 minute contest, with a seven-minute rain delay thrown in for good measure. Worcester scored the game’s only run which was helped by a double error on Cleveland’s usually stellar second baseman Fred “Sureshot” Dunlap.

This game, like many no-hitters, was saved by a defensive gem. Cleveland’s clean-up hitter, Phillips, slapped a line shot to right field that apparently was the end of the no-hitter. Worcester right fielder Lon Knight charged and threw to first base to get Phillips for the out.

While the game got press coverage from the local paper describing it as a “wonderful shut out” and “the best baseball game on record”, the term “perfect game” did not get introduced that day. Richmond himself described his feat as “No-Hit, No-Run, No-Man-Reach First game.” (You could tell he was a pre-med student, not a future marketing major). In fact, five days later, another perfect game was thrown by John Montgomery Ward for Providence.

The Worcester Ruby Legs were gone after the 1882 season. The grounds of the old Worcester Agricultural Fairgrounds were used to build a campus for the private Becker College many years later. Richmond was done himself in 1883, finishing with a 75-100 record to become a doctor. There would be no more “No-Hit, No-Run, No-Man-Reach-First” games until the modern era when Cy Young threw one in 1904 and Addie Joss threw one for Cleveland against Washington on October 2, 1908.

It wasn’t until the following January when a story in the Washington Post quoted the great Chicago White Sox pitcher Big Ed Walsh congratulating Addie Joss for pitching a “perfect game” that the term entered into the unique baseball vernacular.

So, as we continue to ponder today’s game and we see concerns that seem perpetual, we also see that the game, like life, goes in circles. This season Worcester got another professional baseball team as the AAA Pawtucket Red Sox (next door to Providence) moved into a modern, spanking new ballpark. Meanwhile, Becker College, the grounds where their predecessors played, closed its doors due to financial reasons, just as Worcester played its first game in the new stadium just a little over a mile away.

Paul Doyle

Information: Memories and Dreams; Spring 2010; Boston Globe; Kevin Dupont; May 9,2021 article.