Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

THE BASEBALL HISTORY COMES ALIVE BLOG

Please note: As we compose new blog entries, we will now send each one out to all our subscribers as we post them. Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives -GL

February 2, 2021

Bill Gutman

THE SHORT CAREER HALL CALL

Just recently, a colleague of mine wrote an excellent essay on former Yankee first baseman and current Miami Marlins manager, Don Mattingly. Among other things, he noted that Mattingly, known as the Hit Man in his playing days, had six dominant seasons before a bad back robbed him of his power and a portion of his hitting talent. Mattingly toiled on for six more years, playing well but not approaching those six peak years. How good was his peak? This good. During that time, a majority of baseball people called him the best all-around player in the game, also noting his great fielding prowess at first base.

Yet since his retirement, Don Mattingly has never come close to getting a congratulatory call from the Hall of Fame. Most writers, when asked, have the same explanation. He just didn’t have Hall of Fame numbers for a long enough time. It’s an old question. Is a guy who compiles big numbers over a 20-year career but may never have been the best at his position, more of a Hall of Fame player than someone who dominates for a shorter time and has his career cut short or curtailed by injury? In the case above, I think Don Mattingly merits very strong consideration for the Hall.

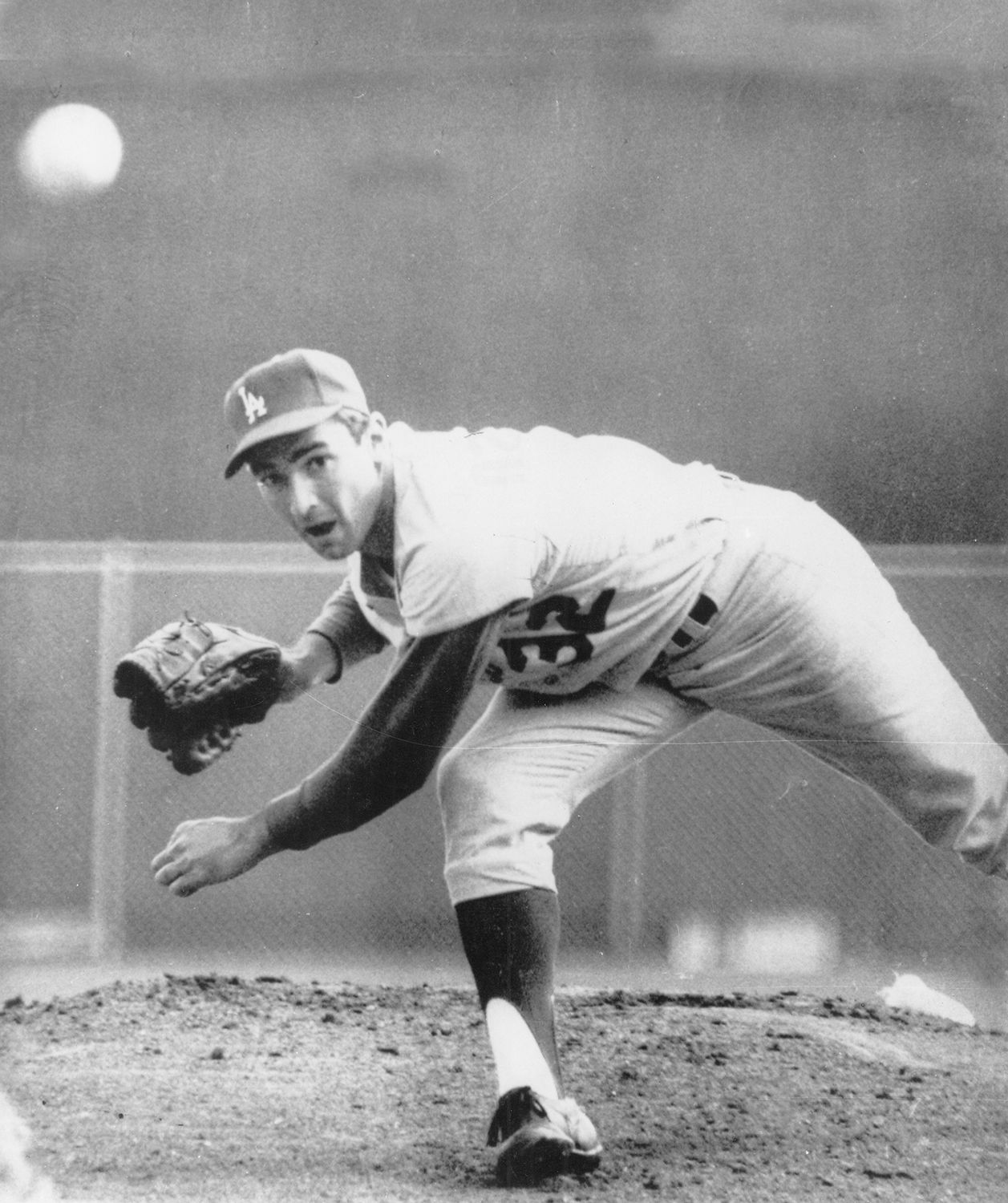

But let’s take a look at two great pitchers, both of whom made the Hall of Fame despite dominating for a relatively short time. I’m talking about Sandy Koufax and Dizzy Dean. For the first six years of his career, which started at age 19, Koufax was a losing pitcher. His record for those years was 36-40 despite being one of the hardest throwers in the game. In 1965, he learned to harness his talent, not overthrowing, and combining his great fastball with a knee-buckling curve. He was 18-13 that year with a 3.52 earned run average, and led the league with 269 strikeouts.

Then, over the next five years, Sandy Koufax exploded. Not only was he the most dominant pitcher in the game, but one of the most dominant ever. His 1962 season was shortened by an injury, but he went 14-7 with a 2.54 ERA. Then over the next four years he was 25-5, 19-5, 26-8 and 27-9. He led the league in earn run average every year and it was under 2.00 three times. He also fanned for than 300 hitters three times, including a then record 382 in 1965. In 1966, Sandy was 27-9 with a 1.73 ERA, led the league with 323 innings pitched and fanned 317. Then he abruptly retired.

Apparently he had an arthritic elbow that had become so painful that he had to call it a career. His final record was 165-87, not normally Hall of Fame worthy numbers. But his total dominance those last five seasons made him an all-time great and a first ballot HOF selection. No one argued.

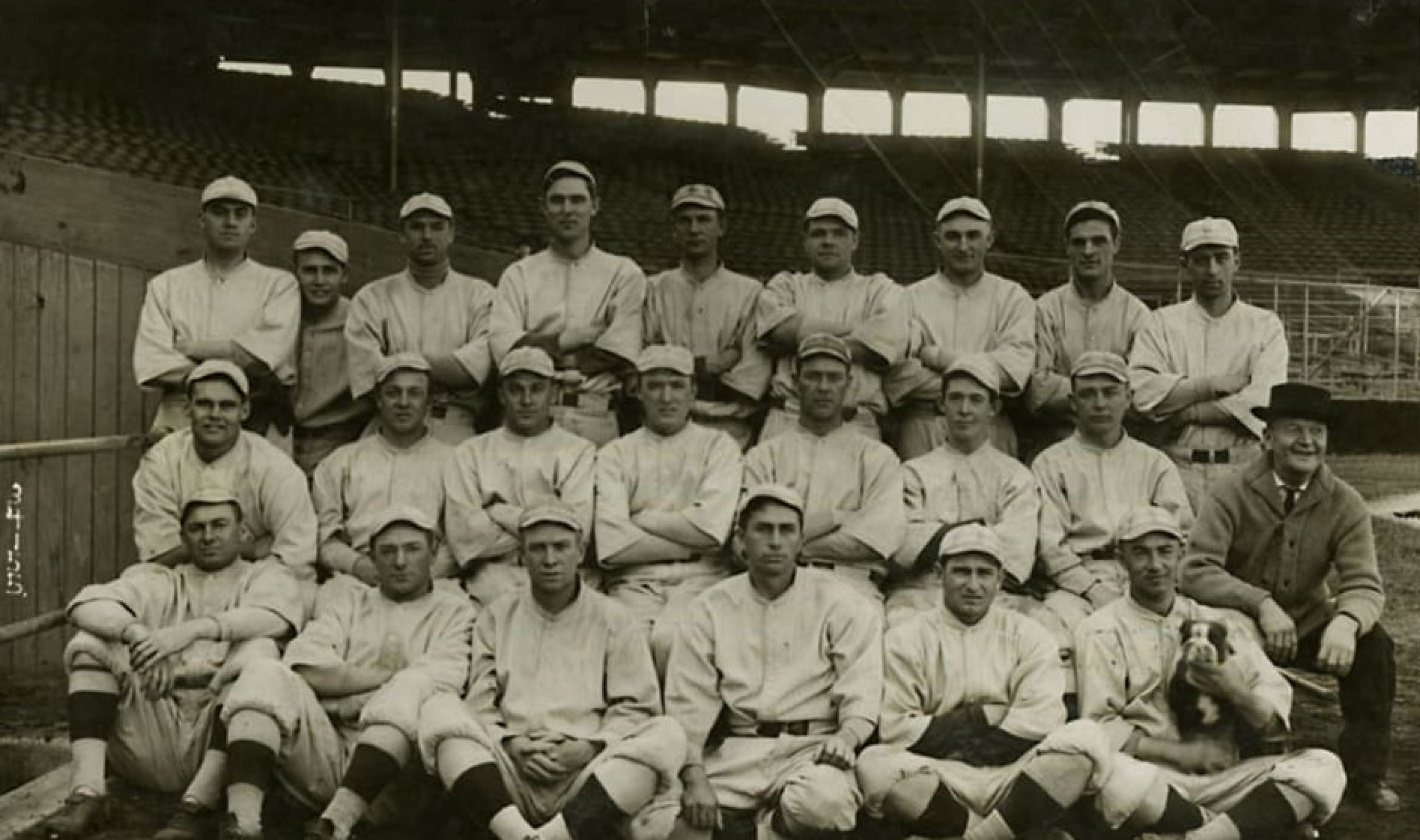

Then there’s the case of Dizzy Dean, one of baseball’s great characters and a great pitcher for a number of years. Unlike Koufax, Diz got off to a fast start. He was 18-15 as a 22-year-old rookie in 1932. He then won 20 or more games the next four years, including a great, 30-7 mark in 1934, the year the Gas House Gang Cardinals were World Champions. That made him the National League’s last 30-game winner. He was 20-18 the year before, then 28-12 in 1935 and 24-13 the following season. Diz was pitching well again in 1937 when a line drive off the bat of Earl Averill in the All-Star Game broke his toe. He tried to come back too soon and hurt his arm. He finished that year at 13-10, and for all intents and purposes his career was finished.

Dean pitched until 1941 and then had a one game cameo in 1947 before calling it quits for good, His combined record in those years was just 16-8, but he was far from the dominant pitcher he had been. He retired with a 150-83 record, a 3.02 earned run average and was elected to the Hall in 1953, getting 79.2 percent of the vote. But was Dean Hall worthy? Koufax dominance was off the charts. Diz had maybe two totally dominant years and two more excellent seasons. Sure, the arm injury robbed baseball of perhaps a generational pitcher, but some feel his election was influenced by his exuberant personality and later work as a broadcaster.

It’s a tough call. I’m not saying Dizzy Dean doesn’t belong, but by just looking at his body of work it can be hard to make a case. And if he’s in, why wouldn’t a guy like Don Mattingly, who was considered the best player in the game for six straight years, be on the Hall of Fame radar? The shortened career certainly makes for a difficult Hall call or, in Mattingly’s case, no call.

Bill Gutman

Let us know what you think. As always, we enjoy reading your comments

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives

Two words to explain why the HOF puzzles one sometimes: Harold Baines.

The old adage: I guess it’s who you know. And, in this case, it pays to know Jerry Reinsdorf.

And many will agree with you, Paul.

The big debate in Boston this week is whether Dustin Pedroia would be an HOF candidate. I think no only because of the “short career” issue. Also, I think every fan who follows their team can “justify” their favorite player getting a shot. I also think that the standards have been lowered over the last 25 years.

Imagine how Tony Oliva would be debated if his shortened career ended now instead of over 40 years ago.

Donnie Baseball has my vote!

Mine too, James.

Right Paul and Gary, Harold Baines was quite good but borderline. Though he was mighty close to 3,000 hits, which is automatic for me.

You summed it up, Bill. There’s no question longevity, durability and sustained excellence counts for Hall consideration (Don Sutton). Also, incandescent brilliance over a relatively short time (Koufax) is undeniable. Dizzy Dean is close, but pales next to Sandy. Flamboyant magnetism didn’t hurt. I’d probably vote yes because of achievement and being one of the great characters in the history of the game.

Mattingly is a tough one. But, as you say, six tremendous years where he was considered the best at his position, plus profound leadership qualities. I’d come down on the side of yes, and can’t understand why he didn’t get a lot more consideration.

Thanks! Bill

Bill:

This is one of those HOF questions that cannot be answered. Apparently the baseball writers, who get the first ten years of voting, didn’t see Mattingly as a Hall of Famer. But the complaint about a lot of the borderline cases — Baines, Jack Morris, maybe even Sutton — is they were never dominant and never the best at their positions. Mattingly was definitely the best at his position for six years, definitely dominant, and often called the best player overall in the game. Yet he’s never come close. It really defies logic.

Well. . .

Lest we become superannuated pitch-men in a revival of ancient beer commercials, feeling “very strongly both ways,” could we perhaps agree that a player whose short(ened) career was so spectacularly dominant for a meaningful period of time, before (or after) languishing in relative mediocrity on account of influences over which he had no particular control, should be favorably considered for induction? That’s my view, but you might tell from the self-conscious care with which these words were just chosen that I agree with Bill: A “brief candle” makes for a tough call. We have traveled this meandering and familiar road before, and I guess that’s part of the allure of a captivating, confounding sport which compels us to keep on doing it without ever quite reaching a permanently satisfactory answer.

By trying to apply this Rube Goldberg standard to the guys mentioned here and a few others, I would argue that Donny Ballgame should be in; Harold Baines should buy a ticket; Roy Campanella trumps Don Sutton by a country mile, and Dave Kingman could be, just might be, and IS a perfect example of a bad example. In this post and an earlier one, Bill’s masterful job of promoting Mattingly for induction becomes conclusively persuasive when one considers the brilliance of an on-field career prematurely curtailed by injury, not to mention (because two Bills already mentioned) DM’s enduring character and other significant contributions to the game. In contrast, Sutton was able to win as many as 20 games exactly once in a seemingly endless and quite decent career as he kept on pitching, season after season, inexorably creeping up on a number automatically but arbitrarily deemed worthy of enshrinement. In my opinion it is he, and not Mattingly, who ought to be regarded as a close call.

What I’m trying (and perhaps failing) to say is that we should be wary of falling prey to a numbers game in assessing the worthiness of a player’s career. That’s what today’s voters tend to do. Three-thousand hits, 300 wins, or 500 homers and — welcome to the Hall! But are those stats all that compelling, in and of themselves? Maybe so, but this whispered voice in the wilderness would submit that they’re an untrustworthy measuring-rod, and they can be a tantalizing invitation to stretch out a career grown mild-to-modest in order to compile talking-points with the writers later on. (I tend to think of Kingman as a one-trick pony, but give him another season and-a-half today, and he could probably, finally, sneak up on 500 long-balls while dusting off an acceptance speech.)

As a kid, I found it tempting and easy to think of Campy and Yogi in a single flight of fancy, even though one of them, roughly speaking, was the “shortened” version of the other. They were the dominant catchers of their time, in New Yawk CITY no less, and the winners of six (6) MVP awards between them But, should a total of twelve-hundred career hits, give or take, = a one-way trip to Cooperstown? If one chooses to home in on that deadly number, one of the greatest catchers who lived could be obliged to wait over there, with Don Mattingly, while BBWAA geniuses consult their slide-rules one more time.

Last, and regrettably least in this age of glittering statistics, please let us remember that such criteria as integrity, character, sportsmanship, contribution to the game, and playing ability should be applied to every candidate for induction, right along with “record.” Those are, after all, the published standards to which movers and shakers at the Hall of Fame give official lip-service, even now.

Well said, as always, Michael. I think those so-called automatic numbers should be taken in the context of the era in which a player performed. I don’t think we’ll have to worry about a 300 game winner again, so the pitching standards may soon have to change. And with everyone swinging for the fences on every pitch today, the 500 home run automatic may soon have to be raised. Instead of King Kong Kingman I submit the case of Fred McGriff. The Crime Dog retired with 493 home runs and has never come close to a Hall call. Yet in 1994, McGriff had 34 home runs in 113 games when the season was halted by a players strike, and 27 runs the next year when the season started late and he played in 144 games. What are the odds that he would have hit those seven extra home runs during the strike time. He probably would have hit at least twice that many. Would that have meant automatic induction? Doubt it, but you never know. We could go on and on with the Hall and the way voting is perceived. Know just what you’re saying about Campy. He was obviously a Hall of Famer. Maybe voters took his Negro League record into consideration, but I don’t think anyone would argue his selection. He and Yogi were both New York icons during the Golden Age of Baseball in the City. Let’s now see what happens with the steroid guys and the guy of questionable character.

Bill

Dean has 3 interesting comparisons with Koufax:

1. Injury truncated each man’s career.

2. Dean’s career numbers = 150-83, 3.02. Koufax’s career numbers = 165-87, 2.76. Each man’s career ERA+ was 131. Pretty close.

3. Something to consider: Dean pitched in the “Hitters’ Heaven” 1930s; Koufax pitched in the “Pitchers’ Paradise” 1960s.

All good points, David. I’m not saying Diz doesn’t belong. As I said, the injury probably robbed baseball as a generational player. He was great. The debate about who does and who doesn’t belong in the Hall is endless. The question I asked was does the guy who was dominant for a shorter time due to injury deserve as much consideration as a long career guy who compiled great numbers but may not have been as dominant. And how short is too short. There’s really no one set answer.

To paraphrase Tom Bodett of Motel 6, Michael, “We left the light on for you.” Its been awhile, but you’ve come back with a vengeance. And, as usual, presented a very articulate well thought out post.

That’s an interesting point about Dave Kingman, who hung around for 16 years. If he had lasted in the Bigs for the better part of two more seasons, we’re talking 500 home runs. So, if you pin me down to my magic number for induction, he would thus qualify–which would be a huge mistake. He was a unique mediocrity who had a generally unsavory personality. However, he possessed long arms and was enormously strong. The ball jumped off his bat. But his lifetime BA was .236 and he once led the league in home runs (37) with a .204 batting average and a league leading 156 strikeouts. Didn’t that BA/HR king set a dubious record? Anyway, he would certainly not belong even with the 500 big ones. But he didn’t get there, so I’m off the hook–mostly.

Baines passes the durability test alright, with a nice .289 over 22 years, along with 2866 hits. But across his vast career statistical landscape there are a dearth of bold, league leading numbers. Also, he was a below average fielder. So, I vote no. But how would I vote if he smacked 3000 balls where they ain’t? Can I plead the fifth? Alright, I’d grudgingly vote yes. As Mason said to Dixon, “You gotta draw the line somewhere.”

Sutton is Hall worthy because he personified longevity, had an unbelievable streak of consecutive pitching starts (as stated by Bill G.), was generally excellent with a 3.27 ERA, had brilliant years, and won 324 games. Plus, he sported a winning personality.

No, as you point out, we can’t be a slave to raw numbers but the 500, 3000, 300 are very good guidelines.

The Don Mattingly “snub” is, as Bill G. wrote, one of those things where the writers just didn’t think his numbers were quite there. My vote here is yes because of all the elements you and Bill mentioned. Ironically, Mattingly told me he felt his power stroke was coming back toward the end of ’95, but being with family trumped the excitement of the game at that point in his life.

Stay well, Bill

All good stuff, Bill. See my answer to Michael about the “automatic” numbers not being quite as relevant today in some cases. I think McGriff getting those seven more home runs, as I mentioned to Michael, is a better test case than Kingman. McGriff was a solid .284 hitter with some 1,500 RBIs to go with his 493 long balls and a very consistent player over the years. Would seven more home runs have made him a Hall of Fame player? Alas, we’ll never know. Agree with you on Mattingly. I’ve heard HOF voters say one question they often ask themselves is whether a player was dominant and the best at what he did. Mattingly certainly was. Vote him in.

Mr. Denny makes a great point the “Hitters Heaven” 1930’s and the “Pitchers Paradise” 1960’s.

Yes, he does.

I totally agree. He was, arguably, the best all-around player in the game for many years! When he came to the plate, I made sure I watched the entire at-bat ……….. and I’m a Dodger fan!

Agree with you, James.

In response to Bill Gutman’s well-taken point.

Koufax was more dominant than Mattingly. Mattingly had some HOF caliber seasons, but not amazing seasons, unlike Koufax. As good as Dean was, Carl Hubbell was better except for one year. I’d have thought twice about enshrining Dean.

Agree. Koufax was an all-time great. But many in the baseball world called Mattingly the game’s best during his six-year run and that’s always been one criteria for the Hall. So you can make a case for him. As for Dean, he could go either way. His strong personality might have helped and the 30-win season didn’t hurt, either. But you can certainly call his induction into question.

mattingly is borderline, but his “big number” seasons were enough to keep his overall career stats really good …

as for pitchers and the dying “300 game winner”, it’s gonna be increasingly difficult to consider voting pitchers into the Hall … i think guys who can’t even pitch 180 innings don’t support the “starting pitcher” role, possibly rendering future pitchers all glorified relievers and failed starters, which is my case against putting relievers in the Hall … baseball has destroyed hitting and action … pitchers go out there and throw as hard as they can for as long as they can, then bring in another and dispense tommy john surgery to the has beens … there has to be reduction in k’s, less h.r.’s, and more action … i vote for smaller pitching staffs, so each pitcher must pace himself … pitching has become too dominant due to specialization

Agree with you on the pitching situation, Stephen. Pitchers aren’t being taught to good deep into games anymore. The so-called quality start is six innings and three or fewer runs. The pitch counts and innings limits don’t help, either. Part of why pitchers can finish what they started. And then there’s analytics with the statistics that show a pitcher can’t go through a lineup a third time. Tell that to Gilbson, Koufax, Palmer, Seaver, Marichal, Carlton, Jenkins and others. They’d just laugh. With the way they handle pitchers today I doubt there will ever be another 300-game winner. It’s all a shame and has hurt the overall game.

Right, Bill, we could go on indefinitely about who should or shouldn’t be enshrined. And, you’re so right, we don’t have to worry about 300 wins anymore. Also, as you say, 500 homers is not what it used to be, what with the jack rabbit ball and hitters taking half swings to tap one over the wall to the opposite field.

In response to Cooldrive, I think Dean should be there because of his spate of brilliance combined with a bigger-than-life personality. The package represents one of the all time forces in the history of the game. It goes to irrepressible. And, without the freak injury, Diz, like Donny Baseball, would have made a bigger statistical dent in the books.

Agree with Stephen Ross about the unnecessarily reduced role of the starting pitcher. Once you relieve a starting pitcher while still effective, after 100 pitches or so, you run the risk that whoever comes in will not be as effective. The odds increase with multiple changes. Until somebody comes in and blows the game.

Nolan Ryan had the best comment on the situation: If a starting pitcher is laboring after 75 pitches, then watch closely as he approaches 100. But if the pitcher is breezing after 75 pitches, there’s no reason why he can’t throw another 50 pitches. That’s 125. Even if you go down to 115 as a limit, I think it would result in more wins and less strain on the pitching staff.

All true, Bill. I said in the blog that Dean may well have been a generational pitcher had it not been for the injury. But I can see the other side, too, regarding his shortened career. Then again, he was a star right from his rookie year but again, playing Devil’s advocate, you can vote on “what ifs.” Still, I have no problem with him being in the Hall. The pitching situation is a joke. Has MLB ever sat down with the pitchers I mentioned above — adding guys like Ryan, Maddux, Randy Johnson, Glavine, Clemens — and asked them why they never blew out the ulnar collateral ligament and what pitchers today could do to throw more innings and preserve their health. MLB just accept the Tommy John surgery epidemic as the norm now and it doesn’t have to be that way.