THE BASEBALL HISTORY COMES ALIVE BLOG

Please note: As we compose new blog entries, we will now send each one out to all our subscribers as we post them. Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives -GL

New Blog Topic: Some Thoughts About Infield Shifts

My friend Bill Gutman and I are both old-school baseball purists, so you can imagine how we feel about some of the new analytics such as “launch angle,” WAR, Win Shares, and others we can’t even pronounce. You can also imagine how we feel about many of the proposed rules changes. Needless to say, we’re against most of them. Bill has written extensively on these points. For the most part, he and I are in agreement.

There is one topic on which we have had differing opinions. That’s infield shifts. They’ve become pervasive in recent years, and I’ve always made the point they are hurting the game. Bill’s view, and he makes a strong case, is that players should adjust and simply start spraying the ball into the open infield spots, taking advantage of what the defense gives them. He quotes Wee Willie Keeler’s old baseball adage: “Hit ‘em where they ain’t!” and adds that if Stan Musial were playing today, he’d have no problem beating the shift. Of course, ideally, Bill is right.

For a while, I had been advocating for rule changes to eliminate shifts. But “upon further view,” I’ve changed my mind. I now feel that shifts are simply a manifestation of deeper problems within today’s game. To use a medical analogy, passing rules to eliminate shifts would be like putting a band-aide over a serious infection. We’d be treating the symptoms without addressing the cause.

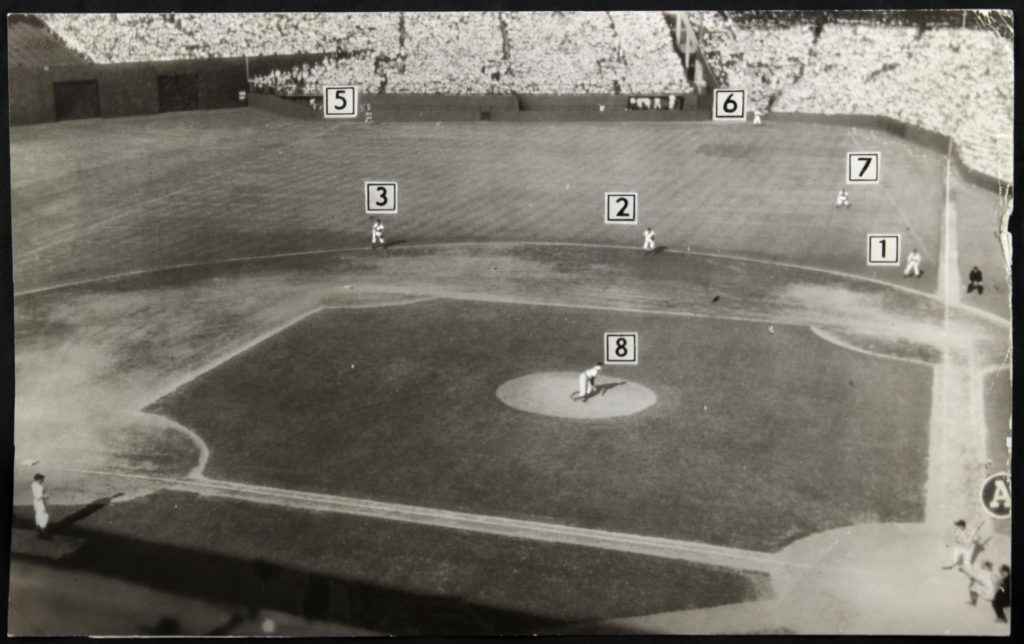

I think we can all agree that shifts were used sparingly in the past. Possibly the earliest was Lou Boudreau’s “Williams shift” employed against the great Ted Williams in the 1940s (see photo above). In today’s game, shifts have unfortunately become commonplace, used even against marginal players.

So let’s examine some of the reasons why they’ve become so popular. Let’s also examine why players are unlikely to morph into modern-day Stan Musials any time soon. Not surprisingly, we’ll find money at the root of the problem.

Why do defenses put on shifts?

The short answer is because they work. The analytic nerds who have taken over the game compile spray charts on virtually every player and feed the information to the manager. The data might say, for instance, that a particular left-handed hitter pulls the ball to right 90% of the time. So why have two infielders on the left field side? Shifting an additional infielder to the right side makes perfect sense. Until the hitter decides to take advantage what the defense gives him, they’d be foolish not to do so. Which begs the next question:

Why do hitters continue trying to pull the ball in spite of the shift?

There are many reasons, but, again, the short answer is that they have a strong financial incentive to do so. Most sluggers are being paid mega dollars to hit home runs. The best way to accomplish this is by raising their “launch angle” and pulling the ball, swinging as hard as possible, hoping to hit a certain percentage over the shift and out of the park. The difference, say, between a player hitting 5-10 home runs a year and hitting 25-30, could be the difference between a $1-2 million salary and a $15 million salary. Perhaps even more. So the incentive is to hit home runs.

Combine this with the advice from the analytic geniuses telling him that home runs are the most efficient way to score runs and thus win games. And now he’s even told it’s OK to strike out a lot while trying to accomplish this. One hundred-fifty strikeouts a year—even more—is common, unheard of as recently as in the generation in which our fathers were watching the game. In addition, managers are now told not to give up outs with small ball strategies like hit-and-runs, steals, or bunts.

Then there are the agents, who also have a strong vested interest. Does anyone believe that agents are going to tell their clients to suddenly start playing small ball again? There’s just too much of a financial incentive with padded home run stats for all concerned.

Here’s another reason to throw into the mix: Players are bigger and stronger than they were a generation or two ago. Maybe PEDs, personal fitness trainers, the big bucks—or some combination of the above—can account for this. At the same time, park dimensions haven’t changed. If anything, the newer parks have gotten smaller. So for whatever reason, a higher percentage of players are now able to reach the fences. Knowing that’s the key to a huge payday, home run totals have skyrocketed in recent years. The juiced baseball hasn’t helped either. As a consequence, with everyone trying to pull the ball and hit home runs, infield shifts have become a logical and effective counter-strategy.

When a player sees a defense shift in front of him, what are his options?

Should he try to chop one into the hole between short and third and “beat the shift” as great players from the past would have done? There’s not a lot of money in that approach. He also realizes that with that extra fielder in front of him, his chances of getting on base by hitting into the shift have gone way down. What used to be a single is now turned into an easy out.

So what does he do? He follows the advice everyone is giving him (agents, analytics, GMs, even his manager), and tries to beat the shift by raising his “launch angle” and trying to hit over it. Each at-bat becomes an opportunity to jack up his home run total.

What’s the result of all this, and what should be done about it?

The sad result is everyone is trying to “go yard” regardless of the game situation. And so, in addition to strikeouts being off the charts, in-game action is severely diminished, and small ball strategies that make the game exciting are almost a thing of the past. As many have observed, the game is turning into a modern-day version of home run derby. Even worse, it’s becoming a bore. In many respects the game we grew up with is becoming unwatchable. And that’s not just me talking. You hear the same sentiment echoed over and over from old-timers and baseball lifers.

Having said all this, I really don’t have a good solution. Increasing home run distances so that what were previously home runs are now warning track outs? That would certainly help, but I don’t think that’s a practical option for many ball parks. Is it time to raise the mound height back to pre-1968 levels? Until we come up with an equitable solution to take away the over reliance on the long ball, I think it’s a problem we have to live with.

If you can come up with a solution that is not just a band-aide over the problem, I’d like to hear it.

Gary Livacari

As always, we enjoy reading your comments

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives