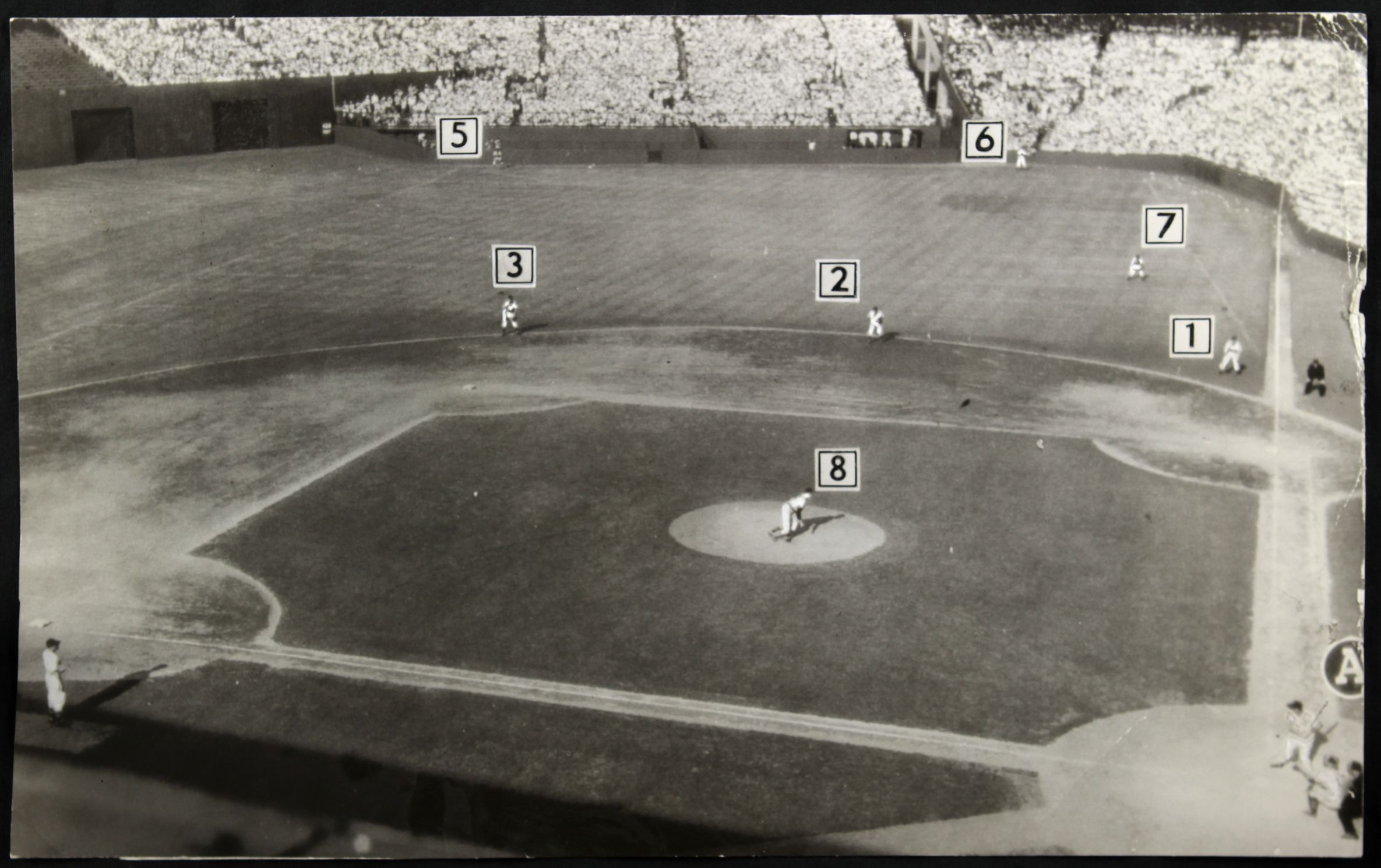

Panoramic Photo Above:

Forbes Field, Pittsburgh

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

THE BASEBALL HISTORY COMES ALIVE BLOG

Please note: As we compose new blog entries, we will now send each one out to all our subscribers as we post them. Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives -GL

New Blog Topic: Some Thoughts About Infield Shifts

My friend Bill Gutman and I are both old-school baseball purists, so you can imagine how we feel about some of the new analytics such as “launch angle,” WAR, Win Shares, and others we can’t even pronounce. You can also imagine how we feel about many of the proposed rules changes. Needless to say, we’re against most of them. Bill has written extensively on these points. For the most part, he and I are in agreement.

There is one topic on which we have had differing opinions. That’s infield shifts. They’ve become pervasive in recent years, and I’ve always made the point they are hurting the game. Bill’s view, and he makes a strong case, is that players should adjust and simply start spraying the ball into the open infield spots, taking advantage of what the defense gives them. He quotes Wee Willie Keeler’s old baseball adage: “Hit ‘em where they ain’t!” and adds that if Stan Musial were playing today, he’d have no problem beating the shift. Of course, ideally, Bill is right.

For a while, I had been advocating for rule changes to eliminate shifts. But “upon further view,” I’ve changed my mind. I now feel that shifts are simply a manifestation of deeper problems within today’s game. To use a medical analogy, passing rules to eliminate shifts would be like putting a band-aide over a serious infection. We’d be treating the symptoms without addressing the cause.

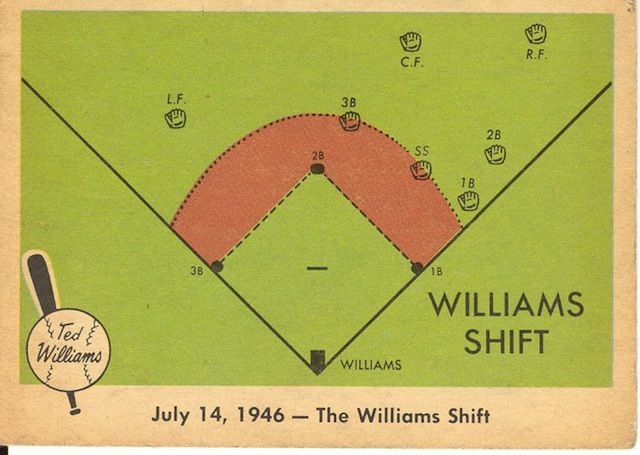

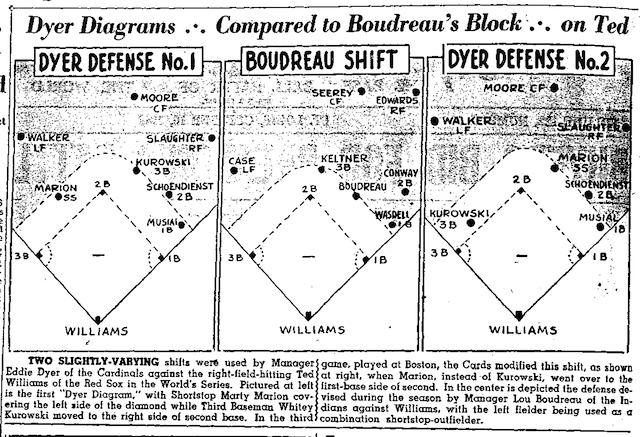

I think we can all agree that shifts were used sparingly in the past. Possibly the earliest was Lou Boudreau’s “Williams shift” employed against the great Ted Williams in the 1940s (see photo above). In today’s game, shifts have unfortunately become commonplace, used even against marginal players.

So let’s examine some of the reasons why they’ve become so popular. Let’s also examine why players are unlikely to morph into modern-day Stan Musials any time soon. Not surprisingly, we’ll find money at the root of the problem.

Why do defenses put on shifts?

The short answer is because they work. The analytic nerds who have taken over the game compile spray charts on virtually every player and feed the information to the manager. The data might say, for instance, that a particular left-handed hitter pulls the ball to right 90% of the time. So why have two infielders on the left field side? Shifting an additional infielder to the right side makes perfect sense. Until the hitter decides to take advantage what the defense gives him, they’d be foolish not to do so. Which begs the next question:

Why do hitters continue trying to pull the ball in spite of the shift?

There are many reasons, but, again, the short answer is that they have a strong financial incentive to do so. Most sluggers are being paid mega dollars to hit home runs. The best way to accomplish this is by raising their “launch angle” and pulling the ball, swinging as hard as possible, hoping to hit a certain percentage over the shift and out of the park. The difference, say, between a player hitting 5-10 home runs a year and hitting 25-30, could be the difference between a $1-2 million salary and a $15 million salary. Perhaps even more. So the incentive is to hit home runs.

Combine this with the advice from the analytic geniuses telling him that home runs are the most efficient way to score runs and thus win games. And now he’s even told it’s OK to strike out a lot while trying to accomplish this. One hundred-fifty strikeouts a year—even more—is common, unheard of as recently as in the generation in which our fathers were watching the game. In addition, managers are now told not to give up outs with small ball strategies like hit-and-runs, steals, or bunts.

Then there are the agents, who also have a strong vested interest. Does anyone believe that agents are going to tell their clients to suddenly start playing small ball again? There’s just too much of a financial incentive with padded home run stats for all concerned.

Here’s another reason to throw into the mix: Players are bigger and stronger than they were a generation or two ago. Maybe PEDs, personal fitness trainers, the big bucks—or some combination of the above—can account for this. At the same time, park dimensions haven’t changed. If anything, the newer parks have gotten smaller. So for whatever reason, a higher percentage of players are now able to reach the fences. Knowing that’s the key to a huge payday, home run totals have skyrocketed in recent years. The juiced baseball hasn’t helped either. As a consequence, with everyone trying to pull the ball and hit home runs, infield shifts have become a logical and effective counter-strategy.

When a player sees a defense shift in front of him, what are his options?

Should he try to chop one into the hole between short and third and “beat the shift” as great players from the past would have done? There’s not a lot of money in that approach. He also realizes that with that extra fielder in front of him, his chances of getting on base by hitting into the shift have gone way down. What used to be a single is now turned into an easy out.

So what does he do? He follows the advice everyone is giving him (agents, analytics, GMs, even his manager), and tries to beat the shift by raising his “launch angle” and trying to hit over it. Each at-bat becomes an opportunity to jack up his home run total.

What’s the result of all this, and what should be done about it?

The sad result is everyone is trying to “go yard” regardless of the game situation. And so, in addition to strikeouts being off the charts, in-game action is severely diminished, and small ball strategies that make the game exciting are almost a thing of the past. As many have observed, the game is turning into a modern-day version of home run derby. Even worse, it’s becoming a bore. In many respects the game we grew up with is becoming unwatchable. And that’s not just me talking. You hear the same sentiment echoed over and over from old-timers and baseball lifers.

Having said all this, I really don’t have a good solution. Increasing home run distances so that what were previously home runs are now warning track outs? That would certainly help, but I don’t think that’s a practical option for many ball parks. Is it time to raise the mound height back to pre-1968 levels? Until we come up with an equitable solution to take away the over reliance on the long ball, I think it’s a problem we have to live with.

If you can come up with a solution that is not just a band-aide over the problem, I’d like to hear it.

Gary Livacari

As always, we enjoy reading your comments

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives

Hi Gary,

I was so pleased to see that you changed your view (naturally since I 100% agree!). The reasons you give are the right reasons for how things got to where they are now and I also agree that it can and should get better. Accepting 160Ks in a season for a hitter with 25 home runs is just a bad evolution for MLB. Perhaps with the slightly deadened ball this year we will see 25 HR guys go down to where the strikeouts outweigh the long ball benefits. I sure hope so. But the shift has to be undone from within the players, managers and coaches from a philosophical standpoint.

As for the ‘new rules’. In trying to roll with it, I am not for the three batter rule for relievers as it takes away from manager decisions that greatly impact the game. Perhaps conversely, I am ok with figuring out having a runner on 2nd sometime in extra innings – maybe starting in the 11th? Teams, players, managers, coaches, and fans can all do without 17 inning ball games that overtax already-thin pitching staffs and afford the teams that face them in coming series to have a distinct advantage. If MLB wanted to have open-ended extra-inning games, the rosters would have to expand even more!

Thanks Mark, glad to see we’re in basic agreement. I don’t like shifts but I decided to look deeper, past the surface to find the evolution and I soon realized, to no surprise, that money was most likely the culprit. And unless you address the underlying cause, it’s foolish to just stick a band-aide over the problem. You raise some good points about the new rules. For the most part I don’t like them, some less than others. I still don’t like the DH, so that tells you where I’m at.

By the way, would you be interested in doing an essay on a baseball topic? I always welcome guest submissions from our readers. If interested, just let me know. Thanks again for your thoughtful response, Gary

Thanks Gary. I think we all share a desire for baseball to remain relevant and exciting without being so far from the game we grew up with. We all get that everything evolves. And it would be my pleasure to do an essay on a topic. I have something in mind but will need a little time to keep up with the high standards set on this site! Mark

That’s great, Mark. Just run the topic you have in mind by me before you start just to be sure it’s one we haven’t covered recently. Any baseball topic is fine, preferably related to baseball history. I usually tell contributors to try to keep it to 800-1200 words, but that’s not hard and fast. Might be best to contact me through email: Livac2@aol.com. Looking forward to hearing back from you. And no hurry, take as much time as you need. -Gary

Good analysis, Gary, with much truth to it. I’ll take one exception, however. It isn’t only home runs that bring the big bucks. The Yanks’ D.J. LeMahieu just got a $90 million deal and he’s a guy who makes contact, sprays the ball all over, hits in the clutch and bats well over .300. He’ll take a home run if it comes, but doesn’t intentionally swing for the fences. If the likes of Pete Rose, Tony Gwynn, Don Mattinly in his prime and others of their ilk were playing today they’d also get the big bucks. If a guy can hit 25 home run s a year but bats .225 while doing it he’s not getting a monster contract. I still think if a single team had the players and teachers, and beat the shift constantly with bunts, opposite field hits and balls in the gaps, and they won, that the shift would once again be used only occasionally and not be the staple of the game that it is today.

Good points Bill, but you also have to remember that most of them are being told and even encouraged to go for the long ball as the most efficient way to score runs and win games. So the higher-ups are OK with the approach. I agree it will take a structural change from the top down, but right now I just don’t see it coming any time soon. Unfortunately, I thnk players with the plate discipline of LeMehieu are pretty few and far between in today’s game.

Agree that it isn’t going to change soon. Thanks to analytics everyone seems to accept the home run or strikeout game. But even Red Sox manager Alex Cora said the game is often boring. When will MLB listen? As for LeMahieu type hitters being few and far between, isn’t that a shame. That’s the way the game should be played. You can have a couple of free swinging sluggers, but you also need the LeMahieu types to balance it all out.

Agree…very well said.

Good points made by you guys. Quickly with Mark–like the 3 batter rule, the less pitching changes the better. Don’t like the runner on second to start the extra frame, but how about placing him at first base, thus provoking more strategy? Stats say teams get weaker the longer the game drags, so anything closer to sudden death is a good thing.

Gary makes perfect sense with money motivating homers, but I’m with Bill on destroying the shift with pragmatic hitting. The money will flow with more hits producing more runs.

The ball is still juiced, players are saying there’s no difference in “carry” this spring. This is what really stinks. Does anybody like a mishit ball going 380′ to the opposite field?

Plus, trying for a blast with upper cut launch angle is overrated. A big, strong guy will hit nearly as many with a level swing, bat higher and drive in more runs. The cream puff batter will hit a few more but suffer the consequences of less contact and less production.

Stan Musial hit his most round trippers in 1948, with 39. He told Sport Magazine he wasn’t trying for home runs. So, he started 1949 trying to hit more out of the park by pulling more pitches. He hit six homers through May with a .272 BA. He went back to his natural spray hitting style. From June on, Stan whacked 30 homers and raised his season’s average to .338.

That’s all good Bill (aka…TOB). Thanks for raising some great points. I think you’re right on everything you said… except for when you don’t agree with me! Haha!

Best,

Gary

aka DD Gary or YFE (which are short for “Double Duty Gary,” and “Your Friendly Editor,” those are Bill’s nicknames for me!)

Oh…you can’t beat fun at the old ballpark! (And where have I heard that before??)

Bill S., I struggled w/the endless pitching changes and as a Met fan at times felt I somehow knew Pedro Feliciano personally! But don’t you feel that’s taking away the ability for the manager to situationally manage the game out by out is a big give-up? As for the runner in extra innings – I am fine with trying different things be it the runner on 1st, or 2nd, the 10th or 11th, or even 12th inning. The total amount of games impacted by these extra innings games is not all that large but it does mess up a pitching staff and just about everybody has had enough after 11 innings anyway!

If we can’t make to the park, DD, we’re happy to settle in at this unique baseball site!

Glad to have you with us, Bill! (TOB)

Back from the mountains of upstate New York for the weekend, so just a brief comment, Mark, on the relief pitcher facing three batters. Managerial strategy is fine, but endless pitching changes dictated by an obsession with statistical analysis only serves to lengthen the game unnecessarily.

And there’s no reason starting pitchers can’t throw 110-115 pitches most times they toe the slab. That would put them into the 8th inning maybe more. Save the bullpen for the times they have to do extra work

Believe me when I say I struggle with this Bill. Serial pitching changes are not great for fans but the strategy change in pitching to 3 just seems to be too much. Maybe I’d be ok with even pitching to two hitters. As for starters throwing 110-115 pitches that actually happens frequently. The difference is that too often those 110 pitches are in 6 innings not 8 or more! Today’s starting pitchers don’t face nearly the amount of soft hitting players as was the case in the 1980s and before. A starting pitcher (like Ron Darling has said) would save a little something extra to get a hitter out late in the game. With hitters taking a better analytical approach and understanding of what the pitchers are doing within the game that they are playing, all pitchers have to pitch all-out, all-the-time. That’s an understated difference in today’s game.

You may know more than me, Mark. But the last time I looked Met managers are still popping out of the dugout most times at well under 110 pitches. Many managers buy into the third time through the batting order philosophy, which gets the starter out by the 7th inning or sooner.

I don’t see the analytical approach resulting in the increased quality of hitting you suggest. Too many at bats are rife with wild swings at pitches way out of the strike zone.

The jack rabbit baseball, that plays more like a golf ball, is the real culprit in fueling the home run or nothing strategy. In 2019, an opposing pitcher doubled off a Met starter with an exit velocity (off his bat) of 108 mph!

You are right on Bill when you note that Met (and just about all teams) have managers or pitching coaches coming out to the mound at far less than 100 pitches much less 110. It seems that MLB is tacitly acknowledging the inconsistency of game baseballs and this coming season it has been reported that the ball will be more consistent and somehow less ‘juiced’ to fly about 2 feet less (how they measure that is a mystery to me). So I agree that plays into the all-or-nothing philosophy you point out. I don’t have supporting data but since it seems almost all players can hit the ball out of the ballpark now (to varying degree) compared to 20 or more years ago, being a late-inning reliever is more perilous than ever. We’ve all seen players hit the ball out of the park to the opposite field on a swing that appeared to just deliver what would seem to be a routine fly ball. Only it’s not! This feeds the desire of all batters for late game heroics.

Yeah, Mark, I read the same thing about two feet less. And, I agree, how the heck do you calculate that distance?

But a couple of reports coming out of spring training indicate the ball is still carrying the way it has over the last two years.

Let’s see what happens when the season starts. Perhaps we’ll be pleasantly surprised.

Bill S.