In the movie “A League of Their Own,” about the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League that lasted from 1943-’54, there is a scene that shows a stray ball land over the fence near an African-American woman, who promptly fires the ball back, implying that the league was, in fact, segregated, and that there were probably many African-American women qualified to play. That African-American woman might as well have been Marcenia “Toni” Stone, the best female player in Negro League history, who would have written the AAGPB’s record book if given the chance. Then again, Toni Stone always seemed to prefer playing against men.

Stone grew up in St. Paul, Minnesota, and as a kid was shooed away from many tryouts, leagues, and teams due to her sex. Her persistence eventually paid off when, at age 15, former Major Leaguer Gabby Street begrudgingly allowed her to participate in a camp at the St. Paul Saints’ Lexington Park when she refused to leave!. He was so impressed by her talent and desire that he encouraged her to keep playing baseball, and she did!

Marcenia, a right-handed hitter and thrower, was a great sprinter, had a strong arm, and was fearless on the field. She was called “Tomboy” often as a child, which over the years became “Toni.”

Toni’s life story is similar to that of hundreds of boys growing up with the dream of playing professional baseball. In an interview in 1991, Stone explained that, “a woman has her dreams, too. When you finish school they tell a boy to go out and see the world. What do they tell a girl? They tell her to marry the boy that their families picked for her. It wasn’t right.”

In 1937, the 15-year-old Stone signed with the local Twin Cities Colored Giants, and, though she didn’t play often, she played well when given a chance. Teammate Harry Davis remembered, “She was as good as most of the men. She could throw just like a man!”

During World War II, Stone wanted to try out for the All American Girls Professional League, but after learning that league was segregated she instead played with the Wall Post #435 American Legion team in the Twin Cities.

After the War, Stone’s family moved to the Bay Area, and Stone played with the San Francisco Sea Lions, a Minor League Negro League team that produced Major Leaguer Bill Bruton; Stone batted around .280 with the Sea Lions.

On December 23, 1950, Stone married Aurelious Alberga, who was born in 1885 and was a First Lieutenant in World War I. Alberga who had been raised in San Francisco, and narrowly survived the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that destroyed 80% of the city, asked Stone to quit baseball and spend more time at home, as most women of the day did. After a year of trying to be a traditional wife, the baseball itch hit Stone hard and Alberga realized he couldn’t keep her away from her passion, and Toni was back on the field in ’52. Stone was anything but traditional!

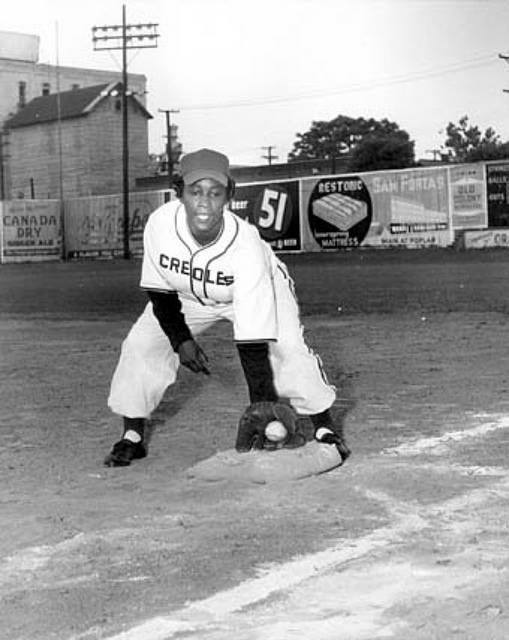

From ’48-’52, Stone played for the New Orleans Creole and each season they played several games against the Indianapolis Clowns; Stone was impressive enough in those games that the Clowns’ business manager recommended her to team owner Syd Pollock who signed her the next season.

The Clowns reported (for P.R. reasons) that Stone was to be paid $15,000 a year, much more than many Major Leaguers, but in reality she made between $300 and $400 a month. She was also advertised as being 10 years younger than she actually was, and as having graduated from college, but years later admitted that she never attended college at all, and never even finished high school.

Stone joined the Clowns in 1953, a year after Hank Aaron was their star shortstop, and she played the first three innings of each game at second base while superstar second baseman, Ray Neil, begrudgingly played left field. Stone’s teammates, in general, did not welcome her to the team or attempt to make things easier for her, but she drew crowds and Pollock let the team know that she was on the team to stay. And though she was very pretty, most of Toni’s teammates remarked that they “didn’t think of her as a date. She was just another ballplayer.”

In Stone’s first game, against the Norfolk Palms, Stone walked in her first plate appearance, and singled home two runs in her second. A week later, against Elizabeth City, North Carolina, Stone walked, singled, drove in two and scored two runs. Against the Norfolk Royals, she drove in two runs, scored three runs and handled five chances without an error, and in a game against the Kansas City Monarchs she singled for the Clowns’ only hit! Stone, like many players before and after her, named getting a hit off Satchel Paige as her biggest thrill in baseball.

Negro League player-manager Double Duty Radcliffe, who had played against famed female Olympic athlete Babe Didrickson who pitched for the House of David team in the 1930s, commented, “Didrickson was good, but we had a girl that played in our league, [Toni Stone], who could really play!”

In general, Stone struggled at the plate like most rookies, batting in the low-.200s, and her fielding was below average for the Negro Leagues. Stone did, however, argue like a Big Leaguer! On close plays she would bark at umpires, and if she struck out or made an error she could swear a blue streak! She always wasn’t afraid of getting into a shoving match or two when a base-runner took her out at second base!

For the ’53 season, according to statistics produced by the Clowns, Stone batted .243 with one extra base hit, and fielded at an .852 clip. Teammate “Woody” Smallwood said that Stone “was a good player, just not up to top Negro League standards.”

In 1954, Stone played with the Kansas City Monarchs, and she helped draw fans when they were hard to come by as the league limped through the post-integration era.

Stone, it was often said, had two strikes against her as a ballplayer in the United States: she was black and a woman. But Stone made the best of things even though she often ate alone in the team bus and knew that many of her teammates resented her. Stone always took the high road, though, and remembered years later, “Some of ’em used to give me a hard time, but I didn’t pay them no mind. They’d say things like, ‘Go home and fix your husband some biscuits!’ They didn’t mean any harm!”

Stone also was envied by her teammates because she was featured in newspaper reports and advertising placards, instead of some of the more experienced players.

Stone retired from the Negro Leagues after the ’54 season but continued to play baseball in the Bay Area for many years.

Stone was elected to the Women’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1993, and there is a baseball field in St. Paul named after Stone. Though her first name was originally misspelled as “Tony,” it has since been corrected.

Her husband died in 1987 at age 103, and Toni, the best female baseball player in history, died in 1996 at age 75 after suffering from Alzheimer’s.