Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

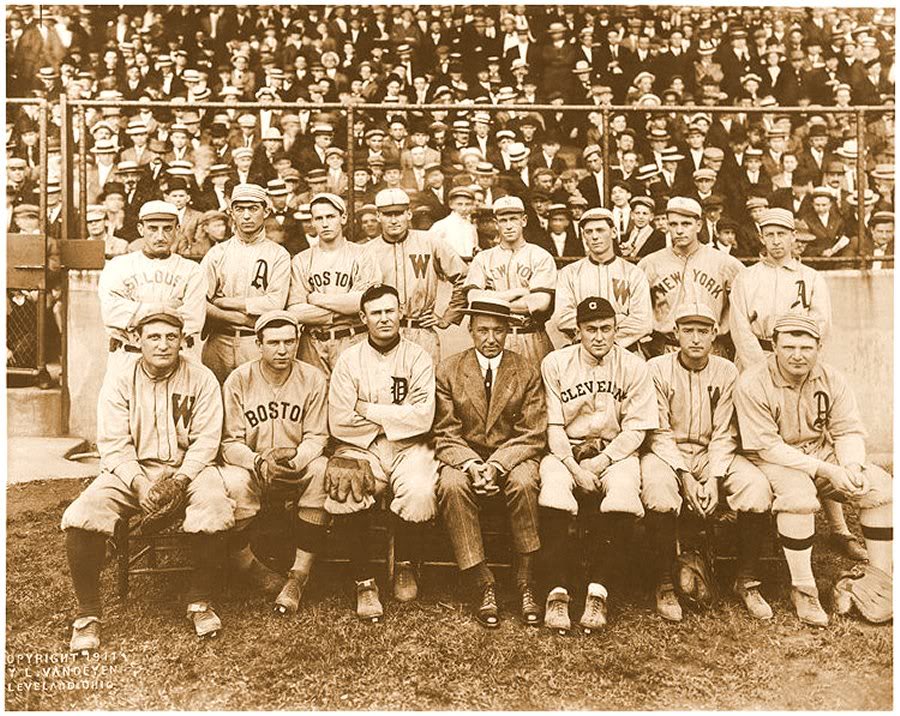

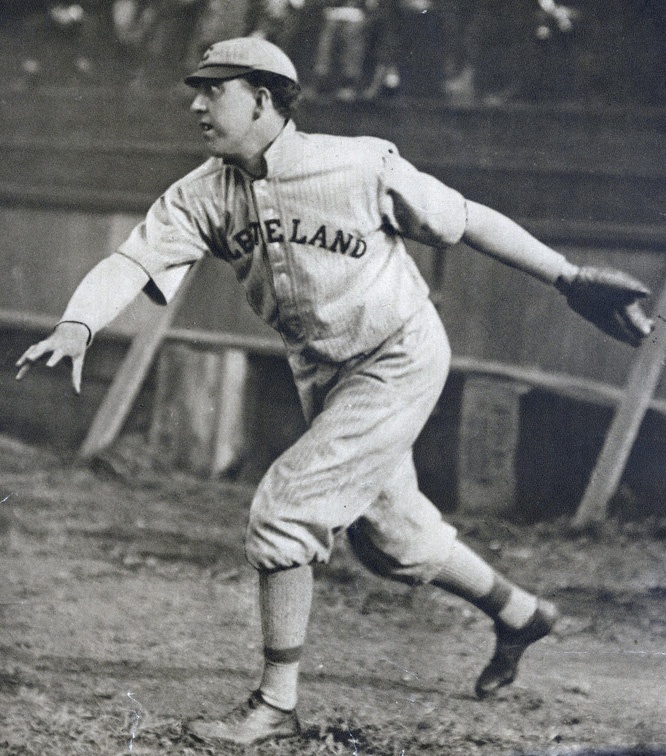

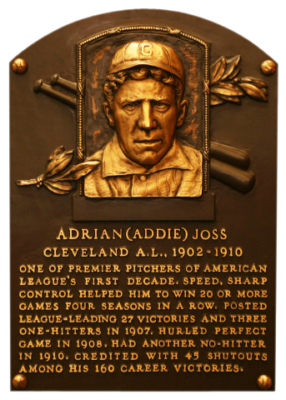

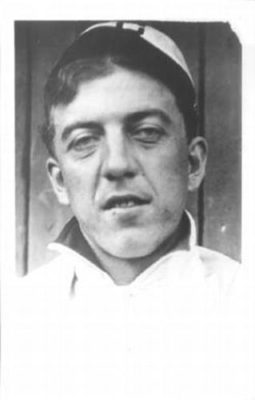

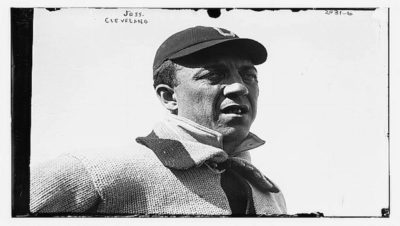

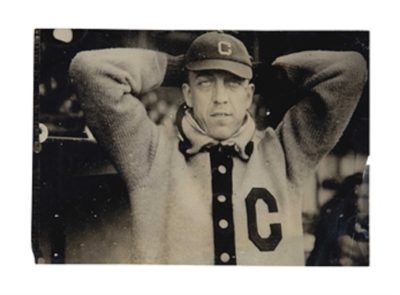

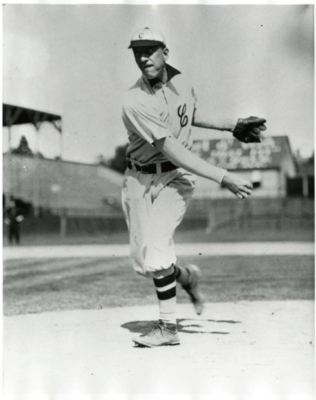

Addie Joss Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Today Michael Keedy takes us back into my favorite time in baseball history, the Dead Ball Era, with this excellent essay featuring “Mystery Player Number Six,” written in his usual, engaging style. The “mystery” won’t be too hard to solve for all our many astute baseball history aficionados…but I think you’ll have some fun with it anyway…and you’ll learn a lot about this often-overlooked, outstanding player to boot!

Come back later today and I’ll reveal the identity of “Mystery Player Number Six” along with a nice photo tribute -GL

Michael Keedy’s Mystery Player Number Six

UPDATE: Yes, Indeed, Mystery Player Number Six is Addie Joss. Very hard to stump our informed readers!

We began this series by casting an astonished and appreciative eye upon big-league icons whose early accomplishments were so inconsequential, even the savviest student of the game had to be shocked by the spectacular careers that lay ahead of them, patiently waiting to unfold and flourish beyond their mid-thirties: The flame-throwing Dazzy Vance, for example, who racked up zero major-league victories by his 31st birthday en route to the Hall of Fame; and a grizzled, intimidating, and productive veteran by the name of Sal Maglie, who sported all of five “Ws” by the time he turned 33.

Despite their obscure beginnings, those two remarkable pitchers somehow managed to collect a grand total exceeding 300 wins between them after their late-term birthdays had already passed them by—and after any absurdly ambitious dreams of ever amounting to much in the majors had vanished, probably, right along with them.

In vivid contrast to these and other ultra-rare late bloomers, Sandy Koufax was a mere 30 when he retired from the game, five years later becoming the youngest-ever Hall of Famer at an age when Vance and Maglie were throwing aspirin tablets, wicked curveballs, and occasional no-hitters in the zenith of their own, glorious careers.

With that little study of sharply disparate baseball biographies in mind, in this chapter we turn our spotlight on another brief candle whose promising flame erupted and flickered out in “the bloom of youth.” As with the Bonus Baby from Brooklyn, his pitching career screeched to a sudden stop when he was but 30 years of age. Like his southpaw counterpart with the golden-but-arthritic throwing arm, this skinny righthander with a confounding delivery suffered from early, frequent medical complications and chronic pain. Totally unlike Sandy Koufax, though, our newest Man of Mystery moldered in his grave longer than any other denizen of Cooperstown before finally receiving his just due: a complimentary ticket to baseball’s national shrine. (Had he lived to see that day, he would have been 98 years old.)

A.J. Foyt, the very first driver to win four Indy 500s, raced to the top of his own favorite sport in mid-century America, and lived to tell about it. In honor of his hurry-up mentality and for the sake of continued anonymity we’ll confer the same “A.J.” mantle on our man here, otherwise known as the “Human Hairpin” for his long, lanky frame and a corkscrew windup-and-delivery that perplexed so many batters throughout his abbreviated but illustrious career. As we shall see, this man squandered no precious time establishing himself as one of the stingiest and most efficient hurlers in major-league history.

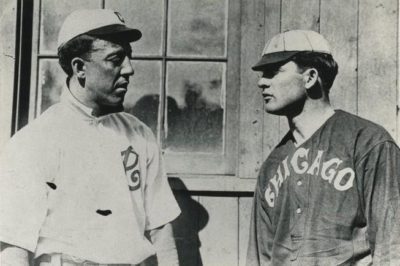

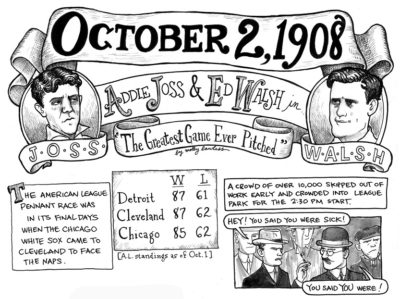

In nine quick seasons, nearly all of which were rendered shorter than expected by illness and injury, A.J. threw only the second perfect game of the modern era, dusting off the White Sox with an all-time record-low tally of pitches (74). Besting his pitching rival and fellow Hall of Famer, Ed Walsh, who lost by a single, unearned run en route to an all-world season of his own, A.J.s early-October jewel helped to pull his team within a half-game of what would have been his only World Series appearance.

In that same season, he rang up a 24-11 record, walking all of 30 batters in 325 innings. Hurling nine shutouts along the way, he won the major leagues’ ERA title with a microscopic 1.16. As in the case of Bob Gibson years later, who was 22-9 with an earned-run average of 1.12 in “The Year of the Pitcher” (1968), fans must have wondered how anybody could lose that many ball games while allowing so few runs. For A.J., the answer was simple: In all of those eleven setbacks, his team managed a grand and impressive total of just 13 runs.

After winning 46 games in two minor league seasons, at age 22, A.J. made it to the majors. He debuted with a one-hitter, losing a career-opening no-no on a disputed call. He won 17 games and led the league in shutouts. In his sophomore year, he won 18, posting a 2.19 ERA and a major-league-best WHIP (walks-plus-hits per inning) of .948. Ominously, particularly for a 23-year-old whose big-league dominance was just beginning to materialize, a high fever stole the Human Hairpin’s final month, very probably depriving him of his first 20-win season in the big time.

Although A.J.‘s 1.59 ERA led the majors the following season, he was laid low by a case of malaria in the spring, pitching enough to win just 14 games. His health seemingly restored at last, he then reeled off four consecutive 20-win campaigns: 20-12, with an ERA of 2.01; 21-9, nine shutouts and 1.72; a major-league leading 27 wins (against eleven losses); and that 24-11 record we talked about above, aided by another nine shutouts, his perfecto, and an infinitesimally low ERA. In that particular year, A.J.‘s “WHIP” of .806 became the fifth-lowest, single-season figure in major league history.

Chronic fatigue messed with his effectiveness the following year, holding him to just 14 wins once more. Nobody knew it, but the next season, when he was able to make only thirteen appearances thanks to a torn ligament in his fabled right elbow, was to be the very last of his tragically blunted career. Even then he threw another no-hitter, becoming the one man in history to deny any hits to the same opponent twice—a feat finally duplicated by the Giants’ Tim Lincecum, more than a century later.

In his nine seasons as a big-leaguer, A.J. started 260 games, completing exactly 90% of them (234). Eight times he ranked among the top-ten pitchers in ERA and WHIP; seven times he was a top-ten finisher in shutouts and fewest walks allowed; for six seasons he occupied the upper echelon for complete games, and in five of those years he was among the top-ten in wins. Never suffering a losing record in the minors or majors, A.J. closed his dazzling career with 160 victories against 97 defeats (.623), despite posting a combined 19-18 record his last two years, while time and breath were growing short. His 1.89 lifetime ERA ranks second to the great Ed Walsh, and his career WHIP, a stunning 0.968, was and remains the best of all time.

Making his final appearance before succumbing to the aforementioned torn ligament in July of season No. 9, at age thirty, A.J. was stricken by tubercular meningitis the following spring, losing his life just two days after Opening Day. Sixty-seven years later, thanks to a special resolution passed by its board of directors, the Hall of Fame belatedly welcomed our A.J. through its hallowed portals and into the permanent pantheon of all-time greats. Today, forty-five years later, he remains the only major league player ever to be enshrined at Cooperstown with fewer than ten seasons to his credit.

A.J., who we now know to be Addie Joss, the son of Swiss immigrants and a rare college man during his early-twentieth-century baseball career, crossed the river of no return on April 14, 1911, two days after his 31st birthday, and two days after his Cleveland Naps’ season opener. He is buried in historic Woodlawn Cemetery, Toledo, Ohio.

Michael H. Keedy

Subscribe to our website, “Baseball History Comes Alive!” with over 1200 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now closing in on the one million hits mark with 970K hits and over 800 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Information: Addie Joss Wikipedia page; and SABR biography of Addie Joss by Alex Semchuck

Addie Joss

Amen.

Wow, this week’s MP is a tough one ! I racked my brain trying to figure out HOF pitchers who played for Cleveland before they were the “Indians”. A vital clue for me was that this guy pitched in a WS. Just a wild guess….could it be Addie Joss ? WOW ! the WHIP stat…..incredible. {Thnx for the education}. Enjoy these MP weekly posts. Thnx, Senor Keedy….and thnx for posting, Gary.

Thanks Tom…glad to hear you’re enjoying the series!