Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

1951 Giants Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

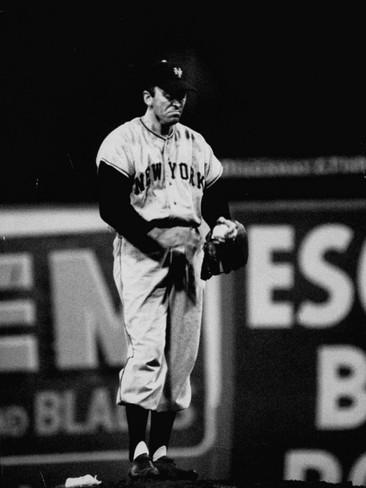

Come back later today around 7:00 PM CT to see who it is that Michael Keedy is featuring today as Mystery Player Number Four. The featured photos above and below offer a hint: He was on the 1951 Giants…and you’ll find him in the photo gallery!-GL

Michael Keedy’s Mystery Player Number Four!

Of Course…It’s Sal “the Barber” Maglie, shown above giving the “Italian Salute” to someone on the opposing team! Thanks to all for participating!

As aficionados of baseball history who know their a-b-c’s might attest, the Hall of Fame has admitted only one guy with just those initials. This particular guy never swung a bat, caught a ball, or threw a pitch at the major-league level – and he wasn’t a designated runner, either. We speak, of course, of [A]lbert…[B]enjamin…(drum-roll here)…[C]handler, dubbed “Happy” for his effusive disposition.

Chandler, whom the owners installed as MLB’s second commissioner, in 1945, was a most remarkable man, for better and worse. A former U.S. senator and governor from Kentucky, he left indelible marks on the game before returning to the world of politics in 1951. Some of those marks helped to set him apart as a humanitarian visionary, and others simply helped to set him apart.

He established the first pension fund for big-league players, a much-deserved benefit that was shamefully overdue by the end of WWII. Over the raucous, disingenuous objection of baseball’s lords, he approved the contract enabling Jackie Robinson to play for the Dodgers, thereby becoming an acknowledged champion of integration at the major-league level, right along with Branch Rickey, Brooklyn’s general manager, and Robinson himself. This could not have been a perfunctory gesture, coming as it did from a son of the South who grew up under Jim Crow’s way of life long before the concept of racial justice came into fashion. (Fifteen of baseball’s sixteen owners spoke loudly but ineffectually in opposition.)

Somewhat further down the spectrum of high morals and righteous accomplishments, Happy Chandler also suspended Leo Durocher for the ’47 season, citing as justification an “accumulation of unpleasant incidents” in the life of the Dodgers’ colorful and combative manager. Unpleasant incidents? This was politico-babble for alleged gambling, and alleged philandering, offenses of which The Lip had been accused, and perhaps already convicted, in the court of public opinion.

But the dopiest of Happy’s moves as commissioner, leaving little room for high-minded discussion, was his ill-fated edict that a five-year ban from the majors be imposed on any player with the temerity to jump to the Mexican League after the war. Eighteen did, including seven members of the New York Giants, and they suffered long-term, adverse consequences for it.

One such victim, and the primary subject of this portrait, was a gentleman we shall call “Sam,” not so much to protect the innocent as to keep our readers in suspense, if possible, for at least a couple of paragraphs here. Born during the first world war, Sam was obliged to shelve his career as an up-and-coming big-league pitcher on account of the second, during which he labored not from the mound but at a defense plant in Niagara Falls. With World War II finally over, he won twenty games in 1946, and again in ’47, while pitching for the Puebla (Mexico) Parrots, spent the next season barnstorming, and in 1949 went home to Buffalo, where he bought a house and gas station. Pretty clearly, Sam was settling into civilian life on a permanent basis. (He was thirty-two years old.)

Well, not so fast. As we know, the bite of baseball’s bug can be infectious, and our man Sam had become hopelessly afflicted. With the aforementioned ban from the bigs finally lifted under threat of litigation, Sam dusted himself off and joined the Giants, for whom he had pitched briefly as a 28-year-old rookie, back in 1945.

By now a well-worn thirty-three, he sported a modest 5-and-4 lifetime record. Three of those few wins had been shutouts, though, perhaps giving Giants’ owner Horace Stoneham a shadowy glimpse of Sam’s remaining potential as he soldiered on in search of — well, middle age, and Win No. 6.

But Durocher, back in baseball’s good graces and managing the Giants, remained skeptical. Considering Sam’s advancing years and spotty history north of the border, his doubts were perhaps understandable. In fact, Leo refused to add Sam to the Giants’ regular rotation until late July. Time was definitely marching on for the old geezer — and we’re not talking about The Babe’s “All-American Out” here.

With the help of just sixteen starts in 1950, our Man of Mystery managed to eke out an 18-and-4 mark, leading the league in winning percentage (.818), ERA (2.71), and shutouts (5). Sam the Bam! Had he peaked? The 34 candles now adorning his next cake certainly contributed to that impression.

Then again, the ’51 season was lightning-in-a-bottle for the Giants. Chasing down and finally overcoming the front-running Dodgers, whose third pennant in five years was all but sewn up by mid-August, the Boys from Coogan’s Hollow were aided and abetted by Sam’s 8-and-1 showing down the stretch, to say nothing about the haunting hex he held over the Boys of Summer in particular. Sam stormed home with a league-leading 23 wins in 29 decisions, which wasn’t too shabby for an aging veteran of the Mexican League. When “The Shot Heard Round The World” reverberated at the Polo Grounds that October, Sam, en route to the shower after pitching the first eight innings, was out of sight, and listening in disbelief.

If you’re on to us by now, and you probably are, you know that Sam continued to pile up impressive records through 1954 (another pennant-winning year), and into ’55, a shortened, swan-song of a season with the Giants. Were it not for a chronically tilted pelvis which played havoc with his pitching motion, his 90-and-38 record over six years in New York, and the .703 winning percentage it generated, might well have been even more impressive than they were. Add back two-plus years lost to the war, two spent chasing phantom pesos offered up by millionaire Jorge Pascual down Mexico way, and two more awaiting an eventual green light back to the majors, and Sam’s 119-and-62 lifetime record would have been immeasurably better. (Means “Hall-of-Fame worthy”!)

By July of 1955 Sam, who was finally about done, was picked up on waivers by the Indians, who used him almost never before selling what was left of him to — wait — Brooklyn, in May of ’56. Collecting a high stack of newspapers for delivery at 5:00 a.m. the next day in beautiful downtown Lincoln, a certain 13-year-old Nebraska boy and Dodger fan caught this headline in The Morning Star: “The Barber Joins The Shorn.” (And now you know.) Standing on what were his last legs, Salvatore Anthony Maglie then went out and set his aging Dodger teammates on fire — and the rest of the baseball world right along with them.

A spittin’ image of Lazarus in yet another, miraculous season, our 39-year-old Comeback Kid posted a 13-and-5 mark for the Dodgers, no-hitting Philadelphia in late September, and helping them clinch their ninth and last pennant on the final day. He finished second in balloting for the very first Cy Young Award, acing out the likes of Whitey Ford and Warren Spahn, and second among all MVP contenders as well, leaving such luminaries as Henry Aaron, Stan Musial, and Willie Mays in his considerable dust. It was definitely a watershed year for Sal Maglie, and his last of any consequence as a big-league pitcher. He retired in 1959.

Sal’s .657 lifetime winning percentage ranks behind a measly seven pitchers in the Hall of Fame. In 1950, his first full season in the majors, he came within one of Carl Hubbell’s record for consecutive scoreless innings, a mark that would stand until beaten by Bob Gibson, in The Year of the Pitcher (1968). Among many others, he pitched in the following, three iconic games: 1. “The Shot Heard Round The World” (October 1951); 2. “The Catch” (October 1954); and 3. “The Perfect Game” (October 1956).

Michael H. Keedy

Subscribe to our website, “Baseball History Comes Alive!” with over 1200 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now closing in on the one million hits mark with 935K hits and over 800 subscribers: www.baseballhistorycomesalive.com