Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Today, our contributor and soon-to-be best-selling author, Michael Keedy – fresh off the release of his new book Top Ten Greatest World Series Catches – returns with another interesting installment in our ongoing series of “Mystery Players,” which also has the subtitle, “Forgotten Stars.” As has been the case with our other entries, this one won’t be too hard to uncover for our very astute readers. Come back later this evening when I will reveal his identity along with a nice photo tribute. In the meantime, I think you’ll enjoy Michael’s trip back into baseball’s past. -GL

Michael Keedy’s Mystery Player No. Seven!

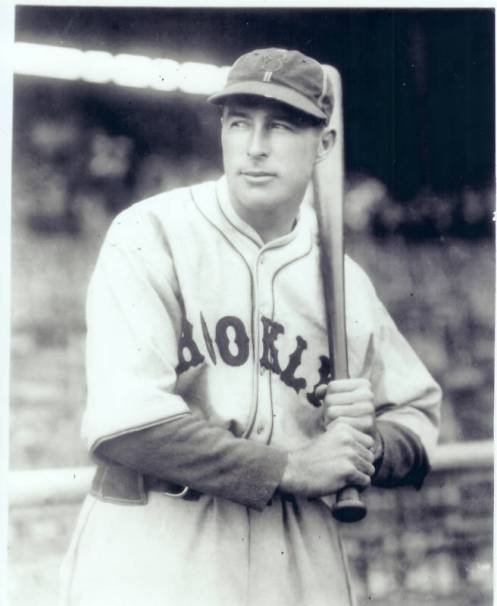

OK…the suspense is over! It is indeed Lefty O’Doul!

“Long live major league baseball!” I shouted that, thought about it, and dreamed it as a kid. (Haven’t we all?) Indeed, since the National League, known as the “senior circuit,” came into existence in 1876, joined a quarter-century later by its junior partner, the majors have sparked the collective imagination of our nation’s young (and young at heart) for nearly 150 years. In that time, more than 20,000 professional athletes have donned big-league uniforms in earnest, haunting baseball parks, sports books, heroic movies and the minds of fanatical civilians from coast-to-coast. As of this writing, just 270 of those many players have made it to the Hall of Fame.

You’d think the proud owners of the top ten, all-time highest lifetime batting averages ever produced across playing careers of ten years minimum (thereby satisfying a key criterion for enshrinement in the first place) all would be found among the 270, sporting commemorative plaques in Cooperstown. Wouldn’t you? Somewhat incredibly, however, you would be mistaken.

On reflection, one can understand the exclusion of one such hitter, as difficult as it might be to justify. We’re speaking now of Joe Jackson, whose banishment from the big leagues in the wake of the 1919 “Black Sox Scandal” made him a hapless if high-profile non-resident of baseball’s fabled shrine on a permanent basis. Just how “high-profile,” you ask? Well, his .356 average over nine full seasons ranks third all-time, behind Ty Cobb (.366) and Rogers Hornsby (.358).

Chasing these three hitters on our top-ten list, but in ascending order, are the following seven icons: 10. Babe Ruth (.342); 9. Dan Brouthers (.342); 8. Ted Williams (.344); 7. Billy Hamilton (.344); 6. Tris Speaker (.345), and 5. Ed Delahanty (.346). Each one has a richly-deserved place in Cooperstown, as you probably know. If you happened to catch the omission of all-time hitter no. 4, you could easily be excused for assuming that he, too, is a permanent occupant of baseball’s inner circle, somewhere in Central New York State. Just an inadvertent oversight, as it were, on the part of Yours Truly.

Well, no. This particular hitting machine, were he among the living, would have to buy a ticket to get in despite his stratospheric lifetime average. Maybe that’s because, like his baseball brethren featured previously in this series, his so-called “lifetime” was so agonizingly brief. Indeed, our man launched his big-league career in his thirties, for all intents and purposes, the year he batted .329 in just 114 games, at age 31.

A former pitching hopeful with an injured and unreliable arm, he had distinguished himself years earlier by setting the all-time, major-league record for most runs allowed (16) by a reliever in a single appearance, chewing up all of three innings to accomplish that dubious feat. With an essentially useless left arm to show for a nothing career at that point, our 26-year-old gave up on what he called “pitching” altogether, retreating to the minors as an outfielder focused on defense and. . .hammering the ball. That is where, and how, his remarkable comeback began. Toiling in the bushes exclusively over the next four, full seasons, he was forced to reinvent himself as a hitter if he had any real hope of battling his way back into the bigs. And oh, how he battled!

By age 32, in just his sophomore year as a major-league hitter, our man led the National League with a .398 average. His 254 hits broke Hornsby’s single-season record, and he rode his 32 homers, 122 runs-batted-in, and 152 runs scored to a second-place finish in voting for league MVP honors, trailing The Rajah’s tally by just six ballots. For added emphasis, this self-taught, newly-minted power producer fanned a microscopic 19 times in 638 at-bats, and managed to reach base an astonishing 334 times in what was then, and remains still, a season for the ages.

Of course we know that one magnificent season does not a Hall-of-Fame career make. In a series of confirmatory encores, our man followed those high-water numbers with averages of .383, .336 and .368, when he again led his league in batting, at the ripe-and-ready age of 35, running third in that year’s MVP sweepstakes (Chuck Klein, Lon Warneke). In his first five seasons as a big-league hitter, he had smoked the ball at a jaw-dropping .365 pace.

But Father Time has a knack for closing ground quickly on middle-agers, and our musty phenom was no exception. He batted .284 and .316 in two final, incomplete seasons, then at age 38 retired to become the most celebrated player-manager in the minor leagues. His lifetime batting average, including time served while shackled to the mound? .349.

With all these eye-catching stats to back him up, why isn’t this late-blooming, tenacious and spectacularly productive student of the game in the Hall by now? One could argue that he’s less worthy on paper than some other members of the top-ten hitters’ club – but let’s not forget his numerical ranking among just the first five of those elites. (Make that the first four.)

One might also say, as the Hall’s voters have apparently done when thinking about it, that five or six dream seasons out of a playing career totaling twice that many doesn’t exactly cut it. Our man set the baseball world on fire, to be sure, but his intense flame flickered and dimmed a little too quickly to achieve the long-range, sustained superiority we’ve come to expect of legitimate contenders for enshrinement.

If our man had done one thing ridiculously well for many years, he might have made it to the Promised Land. If he had kept mashing big-league pitching at a .365 clip for a decade or longer, that is, the Fathers of our National Pastime wouldn’t have demanded he bear the financial freight for admission to their storied museum. If he had fanned three times for every 100 at-bats over that same period, reached base 2.17 times per ballgame on average, sported the power numbers for a dozen years that he actually produced for only seven before his advancing age got the better of him, Joe Jackson would be the one and only top-ten hitter on the outside of a hallowed brick building, still trying to catch a decent look at the plaques of so many lesser-lights within.

But, no. Instead of persisting as a world-class batter for a few extra seasons, our man hung up his spikes to become one of the winningest managers in minor league history (2,000-plus games), the batting instructor Dom Dimaggio described as “far and away the best. . .that ever put on a baseball uniform” (emphasis added), and the father of professional baseball in – Japan, of all places, both before and after World War II.

Instead of being lionized for doing one thing superbly for at least a decade (consistently hitting the cover off the ball), our man has been penalized for re-writing three distinct books: 1. How to own big-league pitchers; 2. How to recognize, coach and develop young baseball talent; and, 3. How to bring the techniques, strategies and allure of major-league ball to an eager, hungry, and appreciative country one giant ocean removed.

Francis Joseph “Lefty” O’Doul was born on the site of what would become Candlestick Park, in 1897. Finally finished with his dominating managerial duties in the Pacific Coast League, and decades of globe-trotting as baseball’s most prominent and accomplished ambassador, he died, 72 years later, back home in his beloved San Francisco.

Michael H. Keedy

References: Wikipedia; Society for American Baseball Research; Baseball Hall of Fame; BaseballReference.com.

Subscribe to our website, “Baseball History Comes Alive!” with over 1200 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now rapidly closing in on the one million hits mark with 996K hits and over 800 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he