Panoramic Photo Above:

Wrigley Field, Chicago

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

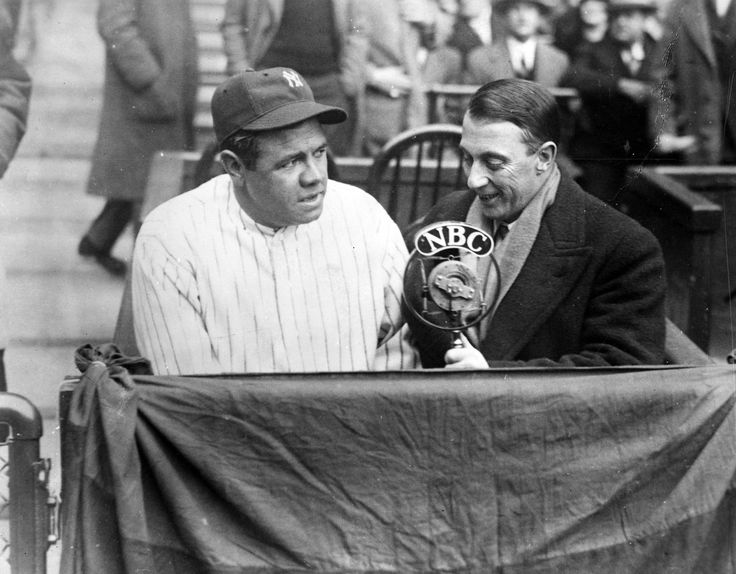

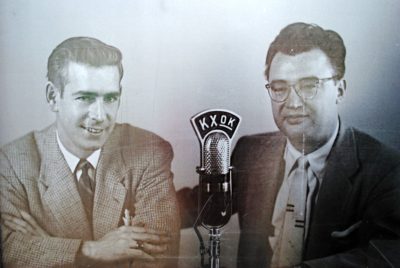

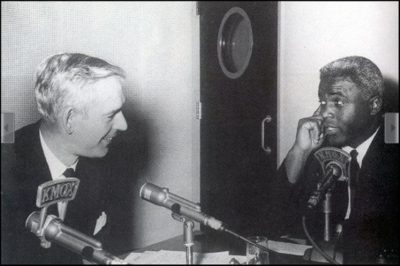

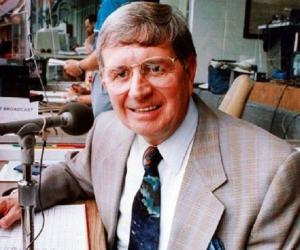

“Legendary Baseball Broadcasters” Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

[Ed. Note: Today, Paul Doyle offers us something a bit different: Paul gives us a brief history of baseball and radio broadcasting. As many of us who are fans of baseball history are well aware, baseball history and American history are deeply interwoven (or more appropriate to baseball, I could say they go “hand-in-glove”!). So I think you’ll enjoy taking a brief respite from reading the exploits of old ballplayers – something we spend most of our time on – and read Paul’s interesting account of baseball and broadcasting. -GL]

I SAW IT ON THE RADIO!

Those of us of a certain age can remember when baseball on television was not a regular phenomenon. Many of us became fans of the game following newspaper accounts and listening on the radio as their favorite announcers made them think the next day that they “saw it on the radio.” Last month, the game celebrated its 100th anniversary of baseball broadcasting games on the radio.

Historically, baseball has always thought of its origins as being pastoral. The myths of players coming out of cornfields in Iowa bring a tear to the sentimental old-timer. But the growth of the game came with the industrial growth of the country. Professional leagues only became viable with the growth of the country’s railroads.

The expansion of the telegraph created thousands more fans who could follow along with their team’s daily travails in their local broadsheet. The sporting press in the 1890s and early twentieth century, the Dead Ball Era, practically invented baseball heroes. National publications like Sporting Life and The Sporting News expanded the horizons of the game and made fans out of the country’s primarily

working class who had no means of going to a big-league game due to geography and economics. Baseball writers during this era became the fan’s window. The writing was more personal and objectivity “thrown out the window,” as the press traveled with the ballplayers on the same trains and established friendships that often violated the principles of journalism. Fans ate up the tales of triumph and tragedy supplied to them by their favorite scribes.

The dynamics of the game also followed the dynamics of the demographics as the country became more industrialized and the population became less and less rural and agrarian. In fact, it was the 1920 census that illustrated for the first time more people lived in urban areas than rural.

During this time, scientific experiments were being conducted to move magnetic

transmission of sound and voices by radio waves. The military used this new way of communication during the Great War (ultimately putting carrier pigeons out of work). Entrepreneurs were developing ideas of how to commercialize this new medium.

Westinghouse purchased the technology with the initial attempt to have radiotelegraph links between its headquarters and its other locations. This was thought to reduce expenses as telephone and telegraph costs could be expensive.

As the technology improved, the company established call letters and experimented with broadcasting outside the company’s range. It broadcast the results of the 1920 Presidential election to just a handful of Pittsburgh residents

who had short-wave receivers to listen. It was a success and they officially went “on the air” early in 1921, broadcasting a religious service. Soon, a curious electrical engineer named Harold Arlin took an interest in announcing important events. He did some boxing blow-by-blow commentary, and the company and listeners were impressed by his rich voice.

As the station tried to find more programming to fill air time, it was suggested that a baseball game be tried. Even though it was the national pastime, some thought it would be boring as a medium (hmm, where have we heard that before?). Arrangements were made to broadcast a late-season game between the local Pittsburgh Pirates and Philadelphia Phillies.

On August 5, 1921, a young Mr. Arlin sat in the stands with a primitive microphone and began to describe the game. Wouldn’t it be interesting to go back in time, sit in the stands, and actually see the reaction fans had to this stranger sitting among them and…talking? After that game, Arlin became the “voice” of the station. Arlin found avenues for the new medium everywhere: cricket matches, more boxing, college football, tennis, and even interviews with celebrities.

After a few years, Arlin stepped back and moved to Mansfield, Ohio to another nonbroadcasting job with Westinghouse, the pioneer company who had led the way. But it wasn’t until the late thirties that clubs woke up to the fact that baseball broadcasts did not cut down attendance, but actually created more interest for local fans to attend the game after “seeing it on the radio.” It opened the door for millions of fans listening on wide signal stations across the country to create broadcasting legends starting with Red Barber, Mel Allen, Russ Hodges, Bob Prince, Ernie Harwell, Vin Scully, Jack Buck, etc, all of whom skillfully “painted a picture” of the green cathedrals and the great players in action on the field.

Still, to many of us, there’s nothing like a warm summer night after dinner to sit out on the front porch or back deck with a cold one and listen to your childhood team create fond memories.

As an epilogue, Jack Arlin was not done with broadcasting. On August 30, 1972, a little more than 50 years after his original baseball broadcast, he was invited to call an inning with Bob Prince of a game between the Pirates and Padres (see photo in gallery). It was even sweeter as, on the mound for the Padres was his grandson, Steve Arlin.

Paul Doyle

Sources: Memories and Dreams Magazine-Summer 2021; “How a 1921 Baseball Radio Broadcast marked the dawn of Sportscasting”-Phil Sheridan; August 4, 2021-History.com

I have many memories, all good, growing up listening to Jimmy Dudley and Bob Neal broadcast Indians games in the 1950s on station WERE. A favorite little “call” that Jimmy would make on a standard up-the-middle, made-to-order double play grounder was delivered in rhyming, sing-song style:

“Over to second, one away

Back to first it’s a double play!”

(and he really did sing it)

Tom,

Baseball on the radio is more visceral. My memories of the voices of the Red Sox are sacred with Curt Gowdy, Ken Coleman, Ned Martin and for the last 39 seasons, Joe Castiglione.

That’s why I love Sirius XM also so that I can listen to everyone’s favorites in their markets- Pat Hughes, Tom Hamilton, Howie Rose, John Rooney, John Sterling. Jon Miller, Charley Steiner…

Ken Coleman did Tribe games for a while (I’d gone off to college, wasn’t listening, don’t know who his partner was) before leaving to broadcast BoSox games. My mom, I remember clearly, was not pleased; she’d already lost Mr. Dudley and Mr. Neal.

Yes. He also was the voice of the Cleveland Browns in their heydays of the 50’s and 60’s.

He called every game that Jim Brown ever played in the pros.

He replaced Curt Gowdy after he left for national prominence on Game of the Week on NBC. Gowdy was already calling games for them for the AFL games.

Thanks for the historical background, Paul. And, yeah, the NY Giants radio broadcasts were a huge part of my summer in 1947, as a nine year-old kid suddenly hanging on every pitch. I kept score listening to Steve Ellis and Frankie Frisch on WMCA. Hall of Famer Frank was a real character, referring to himself as “The Old Flash.” And spouting that great line, “Oh, those bases on balls!”

In 1950, Russ Hodges took over with Ernie Harwell. Loved Hodges play-by-play, “Hit like a bullet!” His Thomson HR call in ’51 was perfect under the circumstances, considering the Giants’ historic comeback and the enormity of the pennant winning “Shot Heard Round the World.”

Red Barber said Hodges’ call was unprofessional. He and Curt Gowdy, both great broadcasters, believed in the complete neutral approach at all times.They were wrong. Fans want to hear the hometown guy behind the mike feeling the same joy and pain of their favorite team. It adds to the broadcast. If out of town listeners are offended, so be it. The trick is to convey the allegiance with class and professionalism. Russ Hodges always did that.

Great insight Bill! I agree 100%! I love what you said:

“Fans want to hear the hometown guy behind the mike feeling the same joy and pain of their favorite team. It adds to the broadcast. If out of town listeners are offended, so be it. The trick is to convey the allegiance with class and professionalism.”

Exactly…

I much prefer the”homers” rather than the ones who let the crowd “paint the picture.” That’s why I never really warmed up to the Vin Scully style. I always much preferred listening to Harry Caray screaming along with the crowd and slobbering into the mike after a Cub victory: “Cubs win! Cubs win!” As I said, I much prefer the “homers.” I only ask that they be honest. Harry Caray epitomized that style. One of his favorite lines when he saw something bad on the field was: “Honestly compells me to say…”

Bill and Gary,

I agree that the hometown announcer is looking after the feelings of the hometown fans. It is a balancing act as nobody wants to hear “Baghdad Bob” denying the obvious. Many want the hometown announcers to call the game as objective “journalists”, but they are more than that. MLB Gameday would do the job there for those who want total objectivity.

On a national telecasts, I think, announcers have to have that Vin Scully “paint the picture” objectivity, so he doesn’t p.o. half the audience.

On a national audience, no doubt. But the home team play-by-play announcer?…that’s another story, and we all have our favorite style. Mine is the Harry Caray version. Honestly, combined with great analysis, passion…and fun! That’s how I remember Harry.