Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

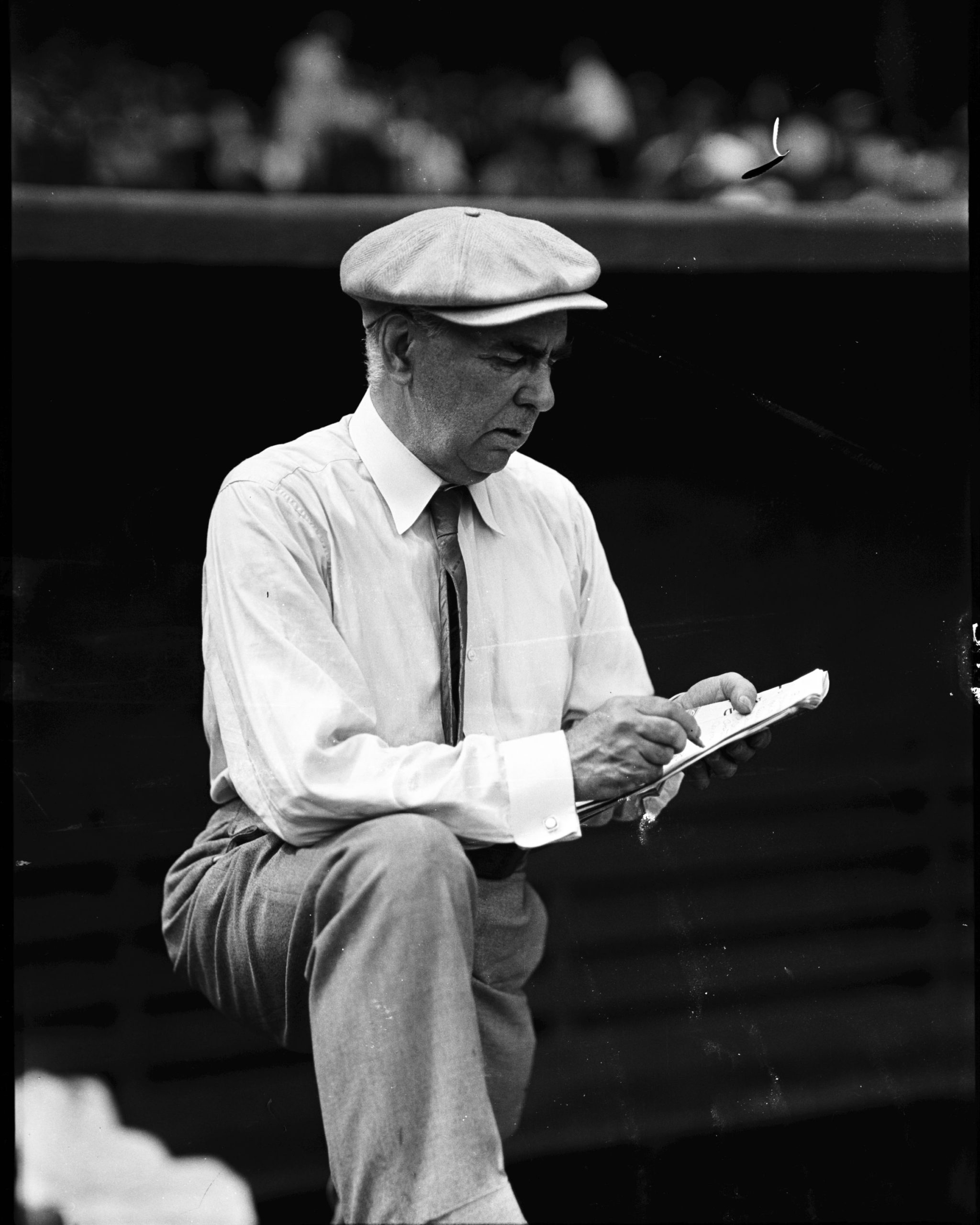

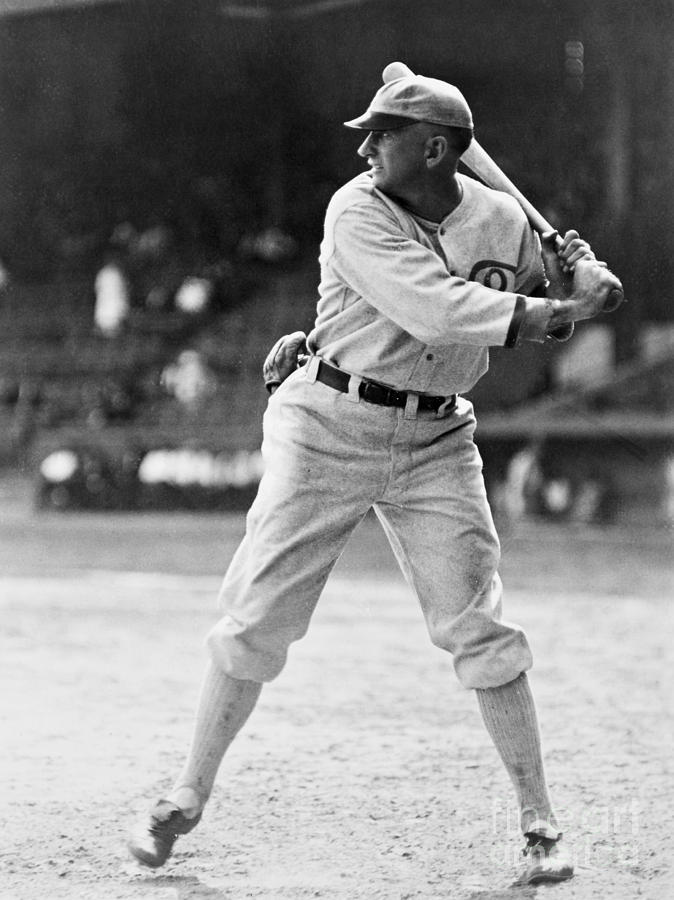

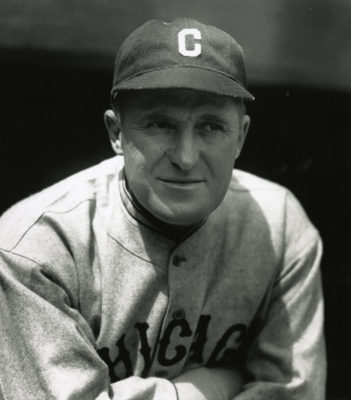

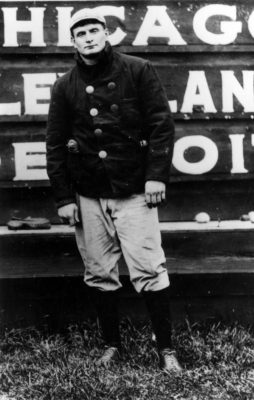

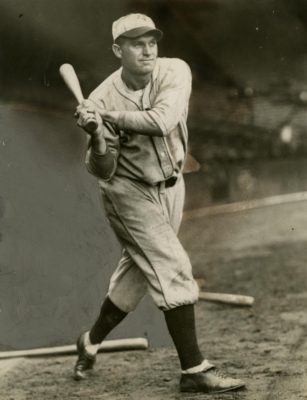

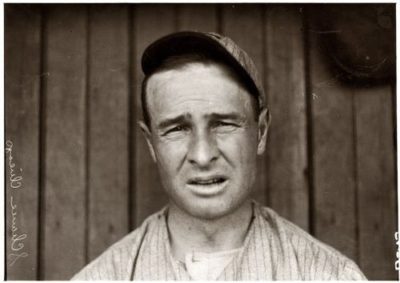

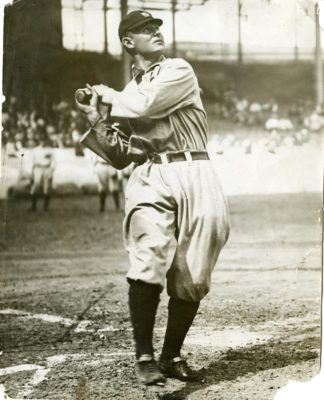

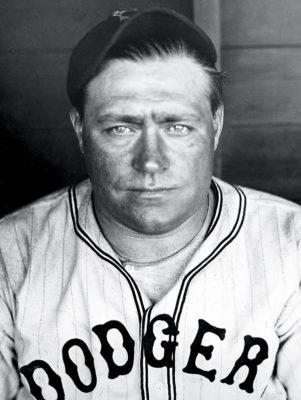

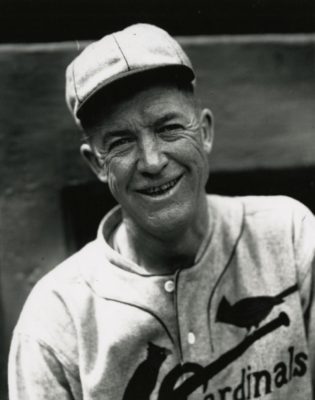

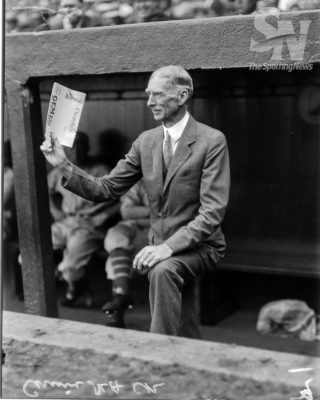

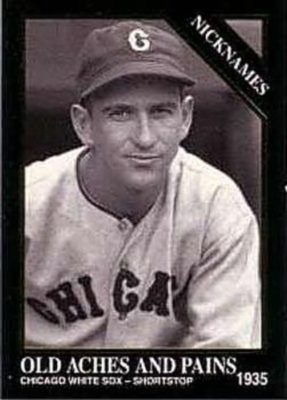

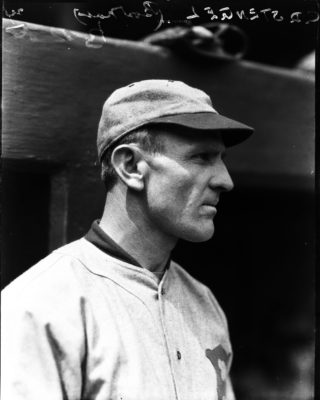

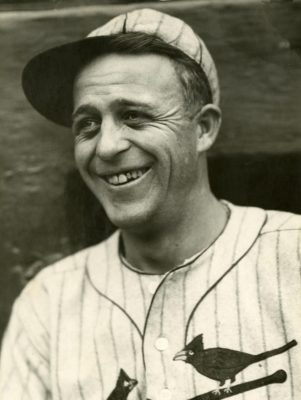

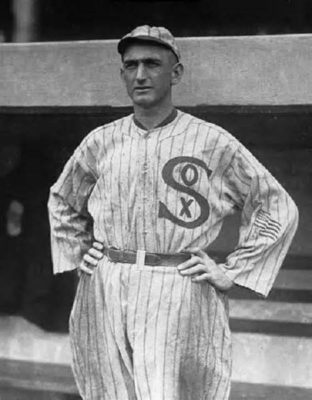

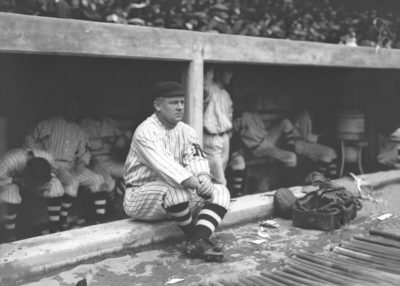

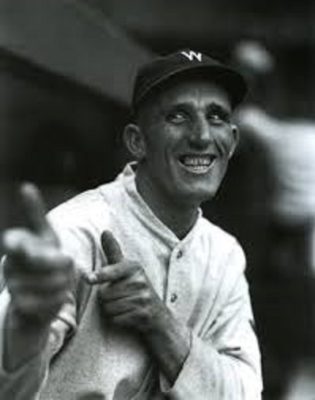

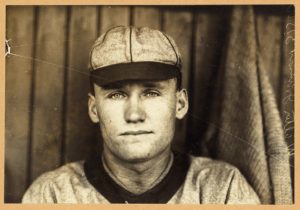

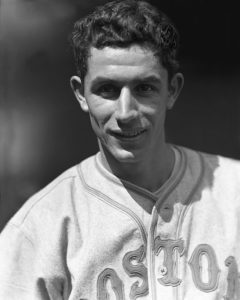

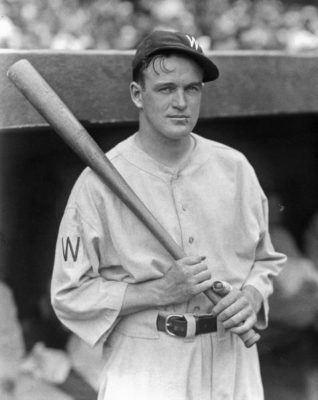

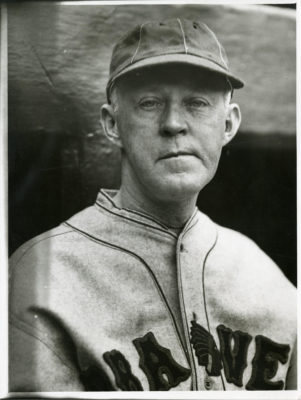

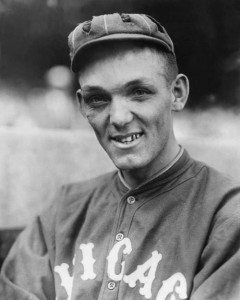

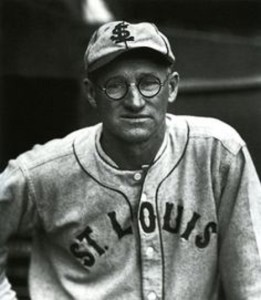

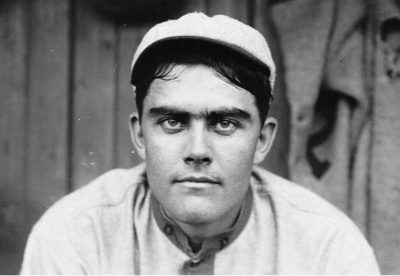

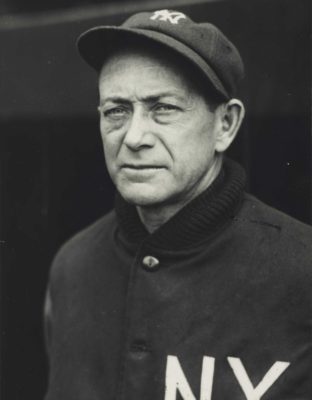

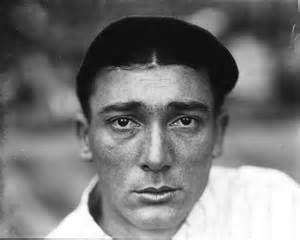

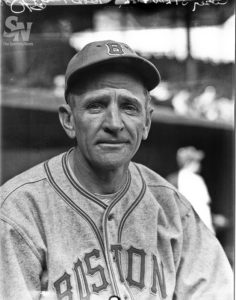

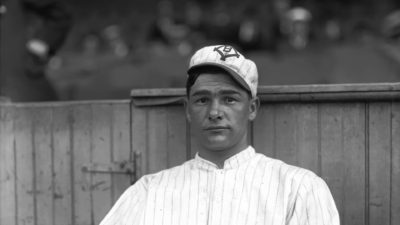

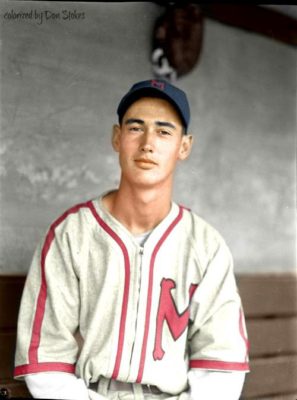

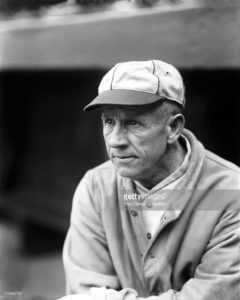

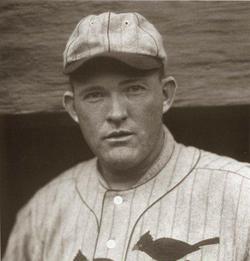

“Classic Charles Conlon” Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size:

Great Baseball Photo Collections, Part Three:

The Charles Conlon Collection

“Baseball’s Golden Age: The Photographs of Charles M. Conlon,” is the best book of baseball photographs ever published.” -Roger Angell, longtime staff writer for the New Yorker

Today, we’ll continue our tour through great baseball photo collections.In Part One of this series, I featured the Leslie Jones Boston Public Library Collection. Last week I presented highlights from the George Brace collection. Today, we’ll examine the Charles Conlon collection, probably the most famous collection from the early decades of the 20th century. Many of Conlon’s photos of baseball’s early stars are considered classics and are easily recognizable to baseball history fans.

Charles Conlon was born in 1868 in Albany, New York, and grew up in Troy, making him a contemporary and possibly a neighbor of Troy native, Hall-of-Famer Johnny Evers. Young Charley Conlon started his career as a proofreader for the New York City newspapers in the early 1900s. Unusual for the times, he had also developed an interest in landscape and nature photography.

Aware of Conlon’s hobby, New York Evening newspaper editor John Foster informed him that Spaulding’s Baseball Guide was looking for a baseball photographer. He was thinking Charley Conlon would be perfect for the job. Soon a new career was born: Conlon was hired as a sports photographer. Years later, in an interview with The Sporting News, Conlon recalled his entry into this burgeoning field:

Foster came to know about my hobby—taking pictures. He said to me one day, “Charley, they need pictures of ballplayers for the Guide, and there is no reason why you can’t take pictures of the players, as well as landscapes. It will be a good pickup for you, and it will be something for a day off.

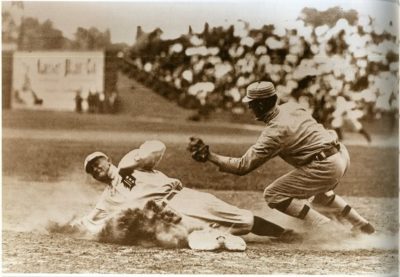

Conlon’s Most Famous Photo

It was indeed a good pickup for him. Over the course of his long career (1904-1941) Conlon took over 30,000 photos, which included thousands of portraits of major league players. It’s ironic that by far his most famous photo is not a portrait, but an action shot of Ty Cobb sliding hard into third base, upending New York Highlanders’ third baseman, Jimmy Austin. The action occurred at Hilltop Park on Saturday, July 23, 1910. The famous photo has historical value as well, as it’s considered the first sports “action” shot ever taken.

As was the common practice of the day, Conlon was actually on the field during the game, he later recalled, “under the hood of a large, tripod-supported Graflex camera.” With Cobb on second, Austin was inching in closer to home, anticipating a possible sacrifice bunt. Cobb broke for third with the pitch, seemingly coming right at Conlon under the hood of his camera. The batter failed to get the bunt down. Austin reacted quickly and backpedaled to take the throw from the catcher. As Cobb arrived, he toppled Austin over as the ball sailed into left field.

In reviewing the box score from that day, I found some interesting, often overlooked information about the game. The Tigers won 6-2, collecting six hits, with Cobb going 1-3 with a triple, two walks, and one run. He also was credited with two stolen bases. So Cobb must have walked and then stole second before the failed bunt attempt and the play Conlon captured at third.

Following him in the batting order was Sam Crawford, and he’s possibly the one who failed to lay down the bunt. The Highlanders’ catcher was Fred Mitchell, who was charged with an error, his first of two for the game. Fred Mitchell had a long career in baseball, managing the Cubs to the 1918 pennant and later becoming a front-office executive with the Red Sox.

The game was played in a speedy two hours, which was typical of games in the Dead Ball Era. The umpires were Hall-of-Famer Billy Evans at home and Bill Dineen in the field, visible in the photo. Sixteen thousand fans were in attendance.

Conlon wasn’t sure he had gotten the shot, but luckily for history, he changed the glass plate before proceeding:

Jimmy turned, backed into the base, and was greeted by a storm of dirt, spikes, shoes, uniforms – and Ty Cobb. My first thought that my friend, Austin, had been injured. When Cobb stole, he stole. Spikes flew and he did not worry where. I saw Ty’s clenched teeth, his determined look…But in a moment I realized he wasn’t hurt, and I was relieved because Jimmy and I were very close friends. Then I began to wonder if by any chance I had snapped the play. I couldn’t remember that I had, but I decided to play it safe and change the plates anyway. I went home licking myself I said: ‘Now there was a great picture and you missed it.’ I took out my plates and developed them. There was Cobb stealing third. In my excitement, I had snapped it, by instinct.”

In 1937 Conlon revealed he had received very little in royalty payments for his famous photo. Most of the payments, he said, had been in the “dime to 50 cents range.” Today, many of his photos will go for five figures at auction.

Also in 1937, Conlon confessed he destroyed hundreds of his original glass plate negatives. We can only speculate as to what treasures may have been lost. As he later explained, he did it because he no place to store them:

“Some years ago, I found that my plates were running me out of the house, so I destroyed hundreds of them. Perhaps it was a mistake, but where would I have kept them? It is possible that had we had a Cooperstown museum at the time, they would have found a haven there.” (Wikipedia)

Conlon retired to his hometown of Troy, New York, where he died in 1945. The 8,300 surviving negatives were owned initially by The Sporting News. Later, in 2010, they were sold to Arkansas collector John Rogers, who was subsequently arrested for fraud involving sports memorabilia. Suits from newspapers and the family of photographer George Burke followed. In December, 2015 a judge determined some of the negatives could be sold to pay off Rogers’s mounting debts. The remaining archive was sold by Heritage Auctions for $1,792,500 in 2016.

I hope you’ll take a moment to glance through the assortment of Charles Conlon photos I’ve assembled in the photo gallery. Many will be easily recognized. I think you’ll enjoy them.

Gary Livacari

Information: Excerpts edited from Charles Conlon Wikipedia page

Click on the green “Follow Us” icon below to subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive to receive email updates of new essays as they are published. Our site has over 1500 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with over 1,228,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Gary,

Great series of the famous photographers of

the Golden Age of baseball from the 1930’s-1960’s when newspapers and radio were the primary avenue to follow the game produced these greats.

Along with the sports cartoonists like Willard Mullins, Gene Mack and later Bill Gallo who painted a picture of players, game recaps and even stadium histories (Gene Mack), I think left more of an impression to the average baseball fan.

Thanks Paul…glad you liked the series!