Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Visit the Baseball History Comes Alive Home Page

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive

Free Bonus for Subscribing:

Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide

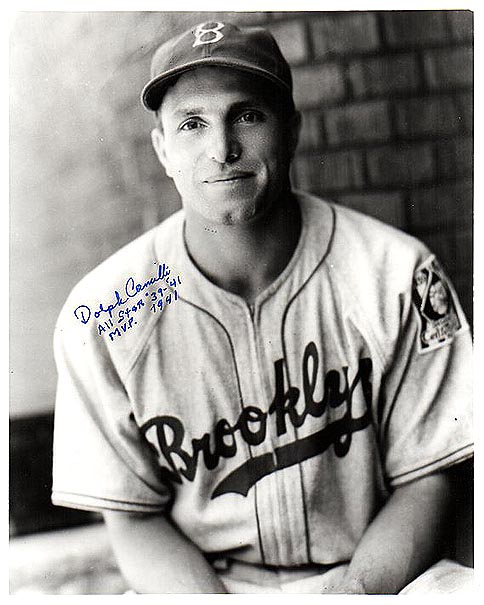

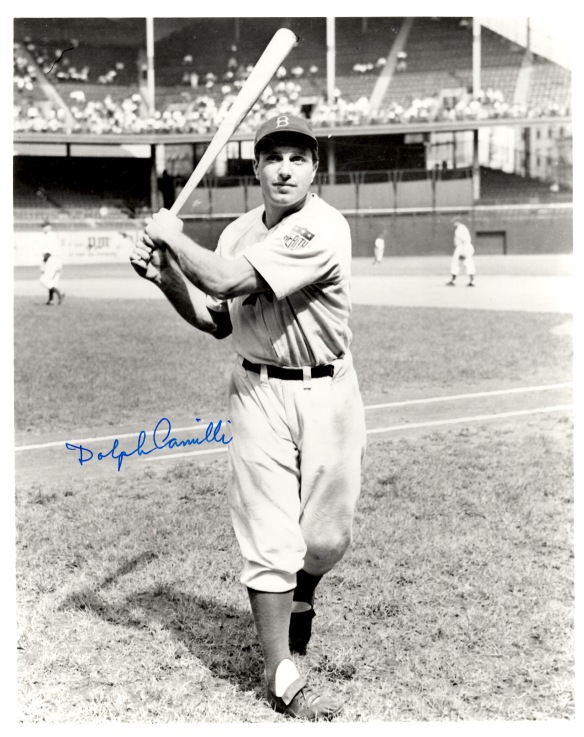

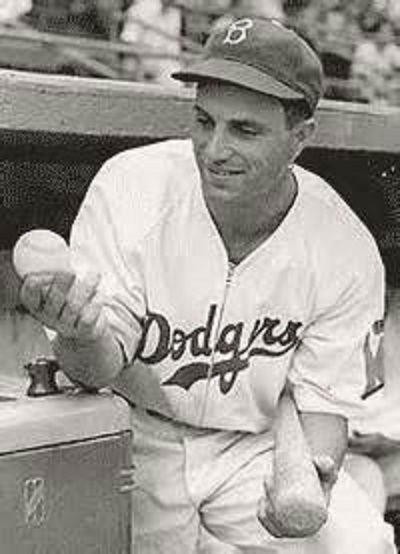

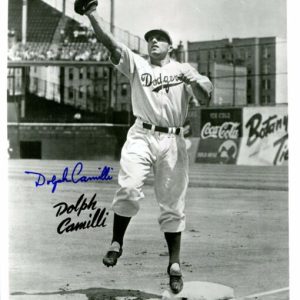

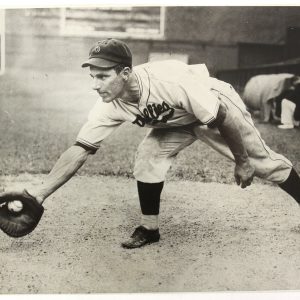

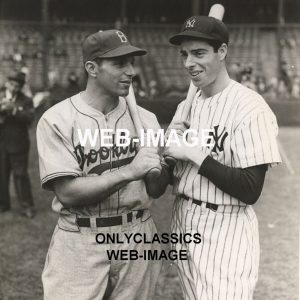

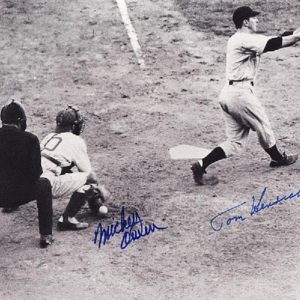

Dolph Camilli Photo Gallery

Today, we continue with Part Two of Bill Gralnick’s interesting essay on former Brooklyn Dodger, Dolph Camilli, whose outstanding achievements have been overlooked over the passage of time. We’re happy to shine our baseball spotlight on this true baseball star from the 1940s. In case you missed it, here’s a link to Part One. -GL

Baseball’s Forgotten Stars

Dodger Star Dolph Camilli

Slugger with a Smile!

(Part Two)

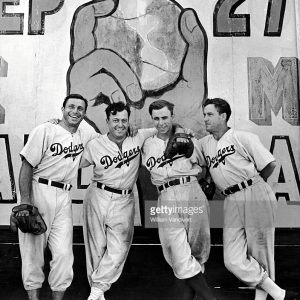

Camilli was also the first building block in the Dodgers’ recovery from a string of dreary seasons described this way by the New York Times in SABR’s profile:” The Ebbets Field seats, (mostly empty) were crumbling, the ushers were surly, and the second division was a perennial address.” This writer assumes it was so bad that “wait ‘til next year” wasn’t even “a thing” for the Dodger fans of those days.

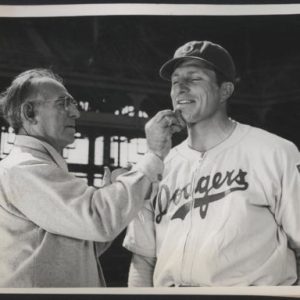

The New York Times said this of Camilli: “Dolph Camilli, a slugging first baseman who propelled the Brooklyn Dodgers to a long-awaited pennant in 1941 and became one of the most popular players in Flatbush, died yesterday in San Mateo, California. He was 90.” The Times’ spin on his career was that he was “noted for his muscular physique and soft hands.” “Camilli’s 34 home runs and 120 runs were both National League highs. He fielded superbly to win the league’s most valuable player award in ’41 as the Dodgers won a pennant for the first time in 21 seasons.”

SABR said he played 5 ½ seasons for the Dodgers, hitting for a combined .270 average. Established as a powerful but errant swinger, SABR said, “He was indeed an important part of the push to the pennant, part of why he was named for the second time to the All-Star team and voted the league MVP.”

Camilli played in each game of the 1941 World Series, taken by the Yankees in five. After a sterling season, he only hit .167 in the Series—three hits in 18 at-bats. He struck out six times and drove in just one run. Ironically, eleven years later, Gil Hodges, his successor at first, had one of the most memorable slumps in baseball history, going 0-21 in the 1952 series. I remember that Series with a sinking heart, but I also remember the fans who lustily cheered their hero every time he came to the plate.

Waiting for the part about being stubborn? One of the most interesting facts about Camilli has to do with another team. While playing for the Dodgers, he built up what was called “a severe animosity” toward New York’s third major-league team, the New York Giants or “Gints” as we said in Brooklyn, and their fans. Maybe this writer got it from Camilli. I almost “plotzed” when the Giants’ ace Sal Maglie, the hated “Barber,” was traded to my Brooklyn Dodgers.

When Camilli was traded to the Giants in July 1943, he refused to report and stayed home for the remainder of the season, returning to work on his cattle ranch in California. He was passionate in his position: “I hate the Giants. This was real serious; this was no put-on stuff. Their fans hated us, and our fans hated them. I said nuts to them, and I quit.”

So, how good was Dolph Camilli? Ken Gurnick of MLB.com researched the statistics of Dodger first basemen. His goal was to pick the top five first basemen in Dodger history. Camilli came in fourth. This is what he wrote: “Camilli’s 1941 campaign won him the NL MVP and helped the Dodgers reach the World Series for the first time since 1921. It was a pretty big deal during the Spring Training of 1938 when the Phillies traded Camilli, who had a 1.034 OPS the previous season.”

Because I know you want to know Gurnick’s rankings, I’ll oblige. Hodges was first, Steve Garvey was second. Third was Jake Durbert (also an April-born first baseman who is worth looking up), who played in 1910 while Wes Parker took the number five spot.

When it was over for Dolph Camilli, it wasn’t really over. He managed, coached, and scouted after the war. He took over as manager of the underachieving Spokane Indians from his mentor, longtime Pacific Coast League baseball figure Buddy Ryan, who was bedridden with pneumonia and engineered one of the all-time comebacks in baseball history. When he arrived on August 3, Spokane, with a 59-52 record, was fourth, 9 ½ games out of first place. The Indians, winning and losing in spurts, had been as low as seventh place, yet Camilli managed them to the championship.

What was his secret? “I laid the law down,” he said in a 1986 interview. “The first day I walked in there, here they were drinking beer in the clubhouse—I raised holy hell about it before the game. I woke’em all up.”

This writer is fascinated when, in his research, he stumbles across someone who he didn’t know was special. It feels good to shout, “Hey! Read about this guy. He was really special!”

Dolph Camilli was really special, folks.

Bill Gralnick

Check out Bill’s Blog: atleastfrommyperspectiveblog

Check out Bill’s books: George Washington Never Slept Here and The War of the Itchy Balls and Other Tales From Brooklyn. Available on Amazon.com paperback or e-book

We’d love to hear what you think about this or any other related baseball history topic…please leave comments below

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive. FREE BONUS for subscribing: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide. https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Your essay compelled me to look up the trade that sent Camilli to Brooklyn. The Phillies gave up Camilli who the previous season hit 27 HRs, drove in 80 runs, batted .339, and led the league in OBP with .446. In return they received Eddie Morgan, a .212 career batter who only played in 39 MLB games prior to the trade and never played a game in the majors after the trade. Oh, yes, the Phillies also got $45,000. I guess they needed the money.