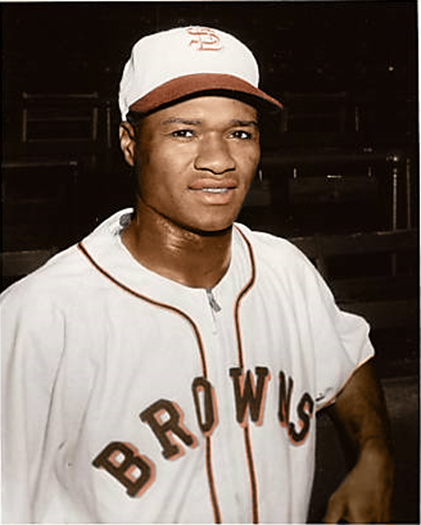

In my opinion, Hank Thompson does not get the notice he deserves in the integration of Major League baseball. Playing with the St. Louis Browns in the summer of 1947, he followed closely on the coat tails of Jackie Robinson (after two months and two days) and Larry Doby (after two days) to break through the “invisible color line” that had kept African-American and dark-skinned Latinos out of Major League baseball. Although the Browns released him that summer, Thompson’s talent could not be denied and he went on to have a productive eight year Major League career with the New York Giants. Born on December 8, 1925 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, the left-handed hitting Henry Curtis Thompson played a part in the historic changing of baseball’s face.

Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League on April 15, 1947 to become the first African-American to play in the Major Leagues in the 20th Century. At that time, Hank Thompson was in his second season with the Kansas City Monarchs since returning from the military after World War II. He had begun playing Negro League baseball in 1943 as a teenaged outfielder with the Monarchs before the military draft. The potential as a ball player he exhibited before military service was coming to fruition. On July 5, 1947 Larry Doby played his first game with the Cleveland Indians to become the first African-American to play in the American League.

Seeing the large crowds Jackie Robinson attracted to ballparks, the St. Louis Browns purchased the contracts of Hank Thompson and his teammate Willard Brown from the Monarch. The Browns were the worst team in the American League with attendance below 1,000 fans during many home games. The team’s management hoped having the black players would generate fan interest. Thompson played his first Major League game on July 17. On July 20, he and Brown made history as St. Louis became the first team to field two African-American players. Their teammates refused to accept them and Browns’ manager Muddy Ruel only used the black players sparingly. The integration experiment did not attract the crowds as desired. With no intention of helping to nurture their baseball talents as the Dodgers did for Robinson and the Indians would do for Doby, the Browns released both Thompson and Brown on August 23. Although he did not get a fair opportunity with the Browns, Thompson showed promise hitting .256 in 27 games playing mainly second base. At only 21 years old, he would get another opportunity to play in the Major Leagues. Unfortunately, being 32 years old, Willard Brown did not.

Thompson returned to the Kansas City Monarchs for the 1948 season and received his second chance the next year when signed by the New York Giants. He along with Monte Irvin made their Major League debuts on July 8, 1949 to become the first African-Americans to play for the Giants. In 1950, his first full year with the team, Thompson hit .289 with 20 home runs and 91 RBIs while playing 148 games mainly at third base and was considered one of the best in league at that position. But he also played in the outfield as he did with the Monarchs. In 1951, the Giants won the National League pennant and played in the World Series against the New York Yankees. Thompson played alongside Monte Irvin and rookie Willie Mays as the Giants become the first team in World Series history to field an all African-American starting outfield.

When Mays left for military service, Thompson hit 17 home runs in 1952 and 24 home runs batting .302 in 1953. When Mays returned in 1954, Thompson hit .263 with 26 home runs and 86 RBIs to help the Giants win the National League pennant. In the team’s World Series sweep of the Cleveland Indians, he hit .364 with seven walks (a four game Series record) and made a spectacular fielding play at third base in Game Three.

Throughout his playing career Thompson battled with alcoholism. By 1956 it dramatically took its toll on him. He became so unproductive the Giants sent him to the minor leagues late in the 1956 season and he retired from baseball in 1957. He died on September 3, 1969, only 43 years old.

Hank Thompson does not have a plaque in Cooperstown as does his former teammates on the New York Giants; Willie Mays and Monte Irvin. However, he should be remembered as one of the Negro League players who proved that once given the opportunity, he belonged in the Major Leagues. His success kept the door open for others to follow.