Connie Johnson’s story is a fairy tale. No player in Negro League history rose to stardom faster, and no player had more fun living the life of a ballplayer than Clifford “Connie” Johnson.

From the age of five, Johnson had only one dream: to travel like his chauffeur brother and visit four places: New Orleans, New York, California and Chicago.

“I don’t think it was luck, but things happened so funny,” Johnson recalled. “God was answering my prayers, but I didn’t know it until four or five years ago–’til I had realized what I did. Because the things that happened to me just didn’t happen like to an ordinary man.”

In early 1940, Johnson had never played baseball in his life. He liked softball, and was very good at it, but wanted nothing to do with “hardball.”

One day, he was in the stands at a friend’s sandlot game in Stone Mountain Georgia, when a player was injured and Johnson was asked to join the game.

Johnson: “I said, ‘No, I can’t play no hardball. I had never caught a hardball. It was hard, that’s the only thing I knew–that it might hurt. They kept asking me so I said, ‘Okay, I’ll go in the outfield but I’m not gonna catch no ball. I’ll pick it up and throw it back and try to get the man out, but don’t ask me to catch it ’cause I’m not gonna catch it, I’m telling you that now!'”

As if written in Hollywood, a ball was hit to Johnson, who made a fantastic catch and doubled a runner off base. Johnson was an immediate star and he loved the attention he got from the crowd!

“Oh man! Now I’m the greatest ballplayer in the world!” he remembered. “Girls trying to catch me and kiss me. Then the team on the other side wanted me to play with them! I wasn’t even thinking about playing ball but that’s how it started.”

Later that week, the Toledo Crawfords and Kansas City Monarchs came to town to play a game and Johnson watched his first Negro League game. He was awed by the skill of the players, but still had no intention of playing baseball. He started out sitting down the third base line, and when Satchel Paige pitched he couldn’t see the ball and assumed the Monarchs were playing “shadowball” in which they pretended to throw a ball around and take infield. But after moving to a seat behind the plate he was able to barely catch a glimpse of Satchel Paige’s fastball. “Boy he could throw! He was old, too. He was in his late 40s,” said Johnson.

While the Crawfords were in Stone Mountain, manager Oscar Charleston and track star Jesse Owens (who had a financial interest in the team) came to visit Johnson on his family farm just as Johnson was about to run away from home to visit the four places he always wanted to see. As the car carrying Charleston and Owens made their way down the dirt road by the farm, Johnson immediately knew who was in the car and why they were coming.

Johnson recalled: “I looked up and saw a black LaSalle about two or three blocks away. I knowed who was in it. I knew what they come for. They come for me to play ball.”

“We heard you have a good arm and want you to play with us,” said Charleston.

Despite Johnson’s explanation that he didn’t play baseball, Charleston wanted him to play a game with the Crawfords and Johnson finally relented. When they got to the game, Charleston told Johnson he was going to pitch–against the Kansas City Monarchs!

“I had a good arm, but I’d never pitched before!” remembered Johnson. Pitcher Spoon Carter had to teach Johnson before the game how to pitch from the stretch, and how to attempt a pick-off throw. Wearing a jersey that was many times too large for his skinny frame (6’-4”, 150), Johnson proceeded to throw five great innings against the Monarchs.

After the game the team was at a restaurant and Johnson, who assumed the game was a one-time deal, wondered to himself what he should charge for his pitching.

“Have something to eat,” encouraged Charleston. Johnson immediately thought that he was going to be paid in food instead of money so he ordered an entire chicken to eat!

But Charleston asked Johnson to play the rest of the season and, snap!, Johnson was a Negro League pitcher. As a matter of fact, with his incredible fastball, Johnson was so good, so quickly, that he made the 1940 East-West All-Star game two months later–the youngest player ever to appear, at age 17! At the time, Johnson didn’t even know what the East-West Game was!

One night that season, Johnson woke Oscar Charleston up in the middle of the night after he had realized his childhood dream had come true!

“I woke up Oscar at 2 o’ clock in the morning. He said, ‘what are you waking me up for?'”

I said, ‘Does our team go to Chicago?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Do we go to New York?’

‘Yeah.’

‘How ’bout New Orleans?’

‘Yeah, we go to New Orleans. They got a team, too.’

‘What about California?’

‘No, we don’t go to California.’

I said, ‘Shoot. This is what I want.’ (Johnson played baseball in California many times in the Majors and Minors). After the Crawfords folded the next season, Johnson jumped to the Kansas City Monarchs and joined a staff with Satchel Paige, Booker McDaniels, John Matchett, Hilton Smith and Lefty LaMarque. Johnson was probably the hardest thrower on a staff in which everyone threw smoke, and in many towns was mistaken for Satchel himself.

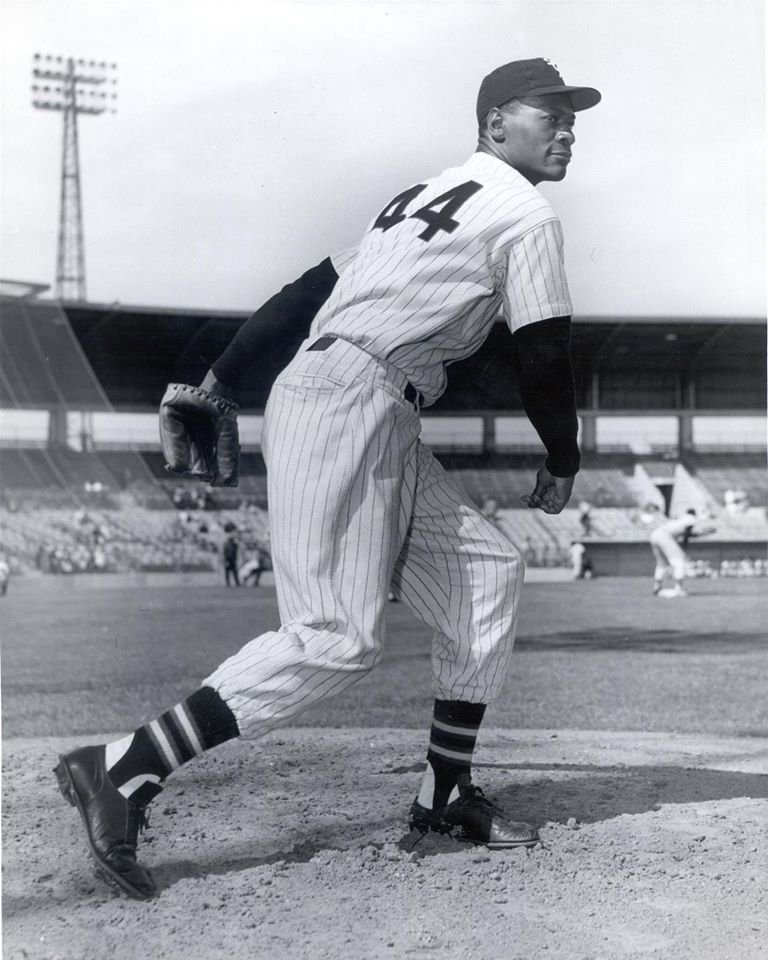

When the color barrier was broken, Johnson was signed by the Chicago White Sox at age 30 and spent parts of five seasons in the Majors. His best year was 1957 when he went 14-11 with a 3.20 ERA.

In his years in the Negro Leagues and Majors, Johnson listed Alec Radcliffe, Harvey Kuenn and Ted Williams as the toughest hitters he faced (Williams got the first two hits off Johnson in the Majors!)

“Things happened so funny!” remembered Johnson. ” I never thought about losing my job, I was never scared of a pitcher or hitter. It was just something! I said, ‘This was just meant to be. It had to be this way.'”

Johnson thought that Major Leaguers of the modern day are about as good as those in his day, but believed they don’t have nearly as much fun. “I see players now,” he remembered. “And they don’t seem like they have fun. We got dressed up and went out on the town!”