Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

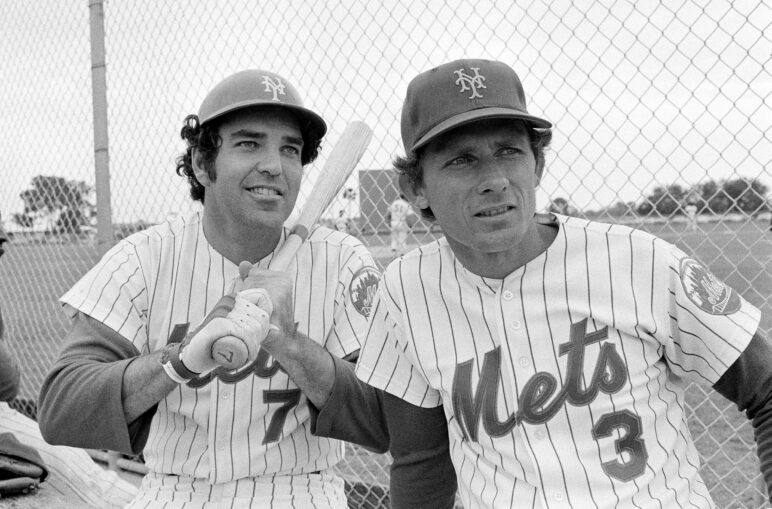

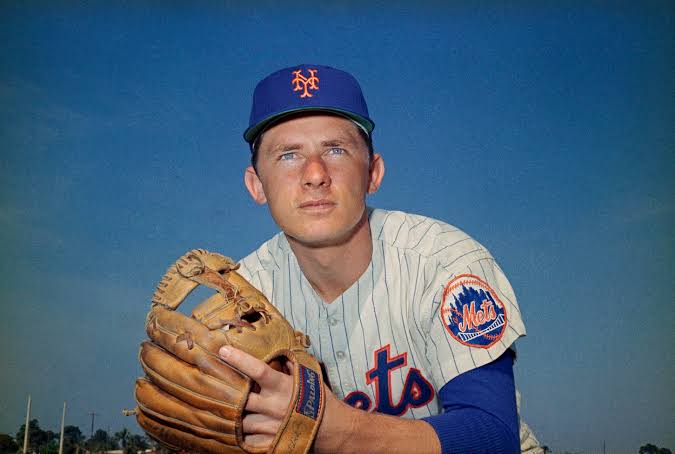

Today Vince Jankoski shares with us a fitting tribute to recently deceased Bud Harrelson with an analysis of his career. Vince addresses the question of how the light-hitting Harrelson (.236 career average) could have survived for 16 seasons in the major leagues. I think you’ll find Vince’s analysis interesting. -GL

Bud Harrelson, RIP

Upon learning of the passing of Bud Harrelson on January 10 of this year of complications from Alzheimer’s disease, I sought to discover how the light-hitting Harrelson could have such a long major league career. Harrelson played 1,533 games over 16 seasons mostly with the New York Mets. He was (more or less) the Mets regular shortstop for ten of those seasons. The Mets were a competitive team during that span, appearing in two World Series.

Harrelson’s longevity cannot be attributed to his bat. In 5,516 plate appearances, Harrelson hit .236 with a slugging average of .288. He hit seven home runs, never more than one in any season. To put this last number in perspective, his teammate, pitcher Tom Seaver, hit 12 home runs in 1,552 career plate appearances. In the 1972 season, Seaver out-homered Harrelson 3 to 1, despite having 400 fewer plate appearances.

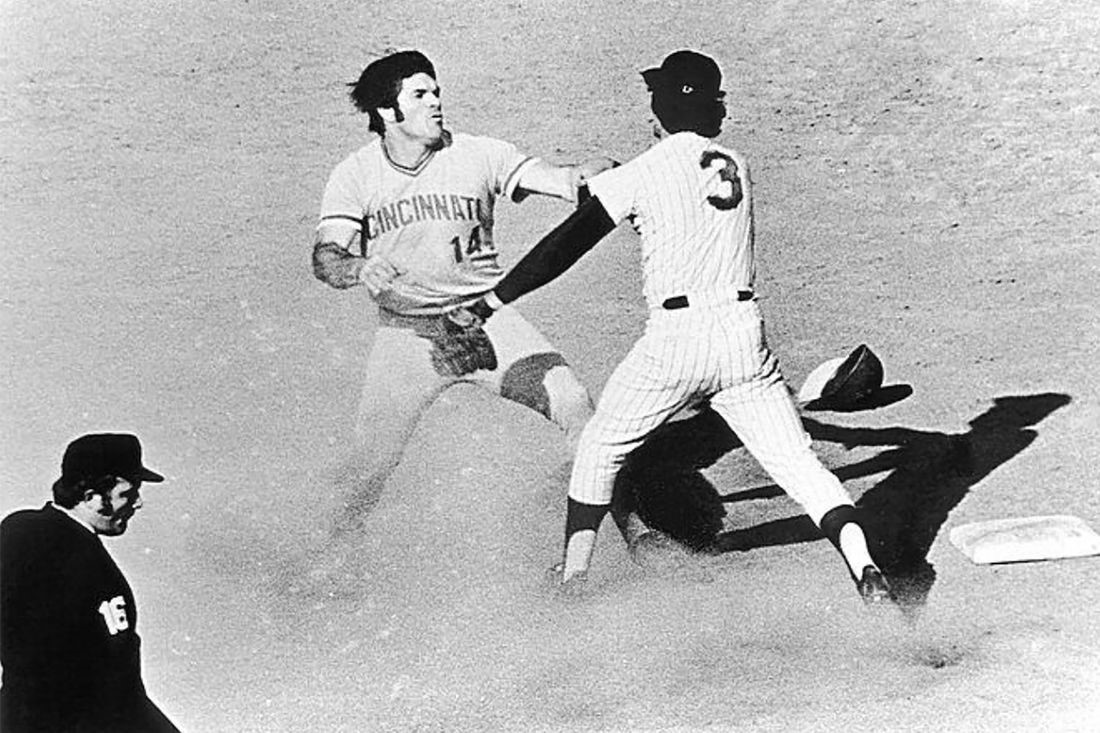

I expected to find that Harrelson had outstanding defensive numbers, but I was disappointed. Harrelson’s defensive numbers (fielding average, range factor, and double plays turned) were very good, but not superior. He won a gold glove in 1971 but lost out in other seasons to Gene Alley, Dal Maxvill, Don Kessinger, Larry Bowa, and Roger Metzger. Harrelson was no Ozzie Smith. Certainly, Harrelson did not win a spot in the starting lineup based on his pugilistic abilities. He lost his only fight to the pugnacious Pete Rose in Game Three of the 1973 NLCS.

Harrelson has been characterized as “feisty” and “scrappy,” however, being “feisty” and/or “scrappy” can only get one so far in the major leagues. Calling a player “feisty” or “scrappy” is damning with faint praise. Ty Cobb was “feisty” and “scrappy”, but that is not what you hear when people discuss Ty Cobb. Likewise, Pete Rose.

One notable thing about Harrelson is that he walked an inordinate amount of times for such a weak hitter. In the 1969 world championship season, he was third on his team in bases on balls, trailing only .340 hitter Cleon Jones and slugger Tommy Agee. In fact, Harrelson’s walk per plate appearance (11.8%) was higher than both Jones (11.5%) and Agee (9.3%) in that season. In the 1973 pennant-winning season, Harrelson was second on the team in walks to Wayne Garrett. For his career, Harrelson walked 11.5% of the time. By comparison, contemporary power hitters and Hall of Famers Willie Stargell (10.4%), Carlton Fisk (8.6%), and Hank Aaron (10%) walked far fewer times than Harrelson.

One could argue that, as a weak hitter, Harrelson would bat eighth in the line-up. The pitcher would follow, allowing the opposing pitcher to pitch around Harrelson. However, Harrelson did not always bat in the eighth slot. In the championship season of 1969, the Mets platooned Ken Boswell and Al Weis at second base. When Boswell played, Harrelson, a switch hitter, would bat eighth. If Weis was in the line-up, he batted eighth with Harrelson moving up to the number two position. For example in the World Series that year Harrelson batted second in games one, two, four, and five against left-handers Mike Cuellar and Dave McNally. Weis batted eighth. In game two, Boswell started against right-hander Jim Palmer. Harrelson batted eighth. So, Harrelson’s inordinate number of walks is not attributable solely to his batting down in the order.

I conclude that Harrelson’s longevity must be a result of his baseball smarts. Although I don’t like to rely on anecdotal evidence, I admit that I watched him play a lot and never saw him make a mental mistake. He was one of those players who, while he would not transform a bad team into a good one or even boost his team up a few notches in the standings, on a contending team he could make the difference between making the playoffs and spending October on the couch. May he RIP.

Vince Jankoski

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with 1,147,000 hits and over 950 subscribers

Loved watching Harrelson play. He was also quite the team player.

As part owner of the L.I. Ducks, he accompanied the team to a series in Nashua, NH.

In one of the games I attended, a downpour interrupted the game. Short of grounds crew, Harrelson ran out on the field and helped them put the tarp over the infield. After the delay, he had a bag of Quick Dry and was throwing it on the wet spots around the baselines and home plate.

And this was the opponent’s home field. Have never forgotten that night.

That playoff game in 1973 proved that a Bud is lovelier than a Rose.

Great info and insights, Paul…thanks!

I was growing up when he was the Mets shortshop and I was a fan of him. One year we went to a game and he was on the bench due to an injury. I recall using our binoculars to watch him in the dugout. RIP Mr Harrelson.

Great info Wendy…thanks for checking in!

Mr. Jankoski hit it “outta da park” with this essay. Thnx for sharing it, Gary. A player with similar background {weak hitter that; none-the-less, helped his team to two WS} was Baltimore’s Mark Belanger. A better fielder than Harrelson, but just as weak with the bat. {.228, 20 HR, 389 RBI}. Unlike Harrelson, controversy was part of Rose’s and Cobb’s make-up. With that in mind, thought I would mention other similar players who were involved in altercations or down-right fistfights : Probably no one was more feisty or combative than John McGraw. Way back in 1894, while playing 3rd for the Baltimore Orioles. Boston Beaneater 2nd-sacker Tommy Tucker slid into 3rd and slightly kicked McGraw going into the bag. Angered, McGraw initiated a fistfight with Tucker. During this, some kids started a fire under the right field stands, which got out of control and burned down Boston’s South End Grounds ballpark.

A coupla confrontations involving Cobb : In 1917, during a spring training game in TX, he got into a dispute with NY Giant “Buck” Herzog, that continued into a knock-down, drag-out “knuckle-buster” in Herzog’s hotel room. In 1921, Cobb was infuriated by a call by umpire Billy Evans that resulted in them going “mano-a mano” in the hallway to the locker room. Other famous incidents are : St. Louis’ Joe Medwick and Detroit’s Marv Owen getting into it after a hard slide at 3rd during the 1934 WS, resulting in Medwick getting removed from the game by Commissioner Landis. In 1965, Juan Marichal tries to bean John Roseboro with his bat. In 1993, Robin Ventura unsuccessfully takes on Nolan Ryan, {who is 20 yrs. his senior}. And more recently, in 2016, the much smaller Rougned Odor throws a well-aimed “haymaker” at Jose Bautista after a play @ 2nd base. Ah, as fans, the bonus we sometimes get to watch not only baseball but; at times, wanna be MMA fighters disguised as MLB players. 32 days until Opening Day ! “PLAY BALL” !

Thanks Tom…I’m sure you’ve seen quite a few altercations on the field when you were calling balls and strikes behind the plate!

Actually no, Gary. In 29 years of working all kinds of youth baseball and high school, I only had maybe a handful of times that a couple of players briefly shouted something at each other after a play {mostly after a hard slide or a pitch that buzzed too close to a batter’s melon}. Never had anything come close to a physical confrontation between players, coaches, or to me and/or my partner[s}. I also worked some adult 25U and 40U baseball for a few years. That’s where you’ll find the real cry-babies; trying to emulate what they see in MLB. Mixed in were some guys that had played some DI or DII ball, but were never drafted. Their lack of rule knowledge was pathetic. Hope you eventually get some “baseball friendly” weather in C-town ! Thnx.

Then, there are the fights that don’t happen. I have read that nobody went toe-to-toe with Walter Alston. And there was Craig “Puff the Magic Dragon” Nettles who would disappear whenever a fight broke out. I am told that when Jack Del Rio was catching Randy Johnson at USC, batters behaved themselves.

Two comments:

1. I quite agree with Mr. Jankoski that Harrelson’s ability to draw walks was an offensive asset. Since walks, like hits, are plate appearances where an out is not made (the key to scoring runs), walks are valuable. My rule of thumb is that a hitter should have an on-base percentage 0.5 points above his batting average. Thus a hitter with a.250 batting average should have a .300 on-base%. Harrelson’s — .327 OB% minus .236 BA: 0.91% — is excellent.

2. Mr. Marshall’s comment that Mark Belanger was a better fielder than Harrelson understates the difference by a large margin. Harrelson won one Gold Glove at shortstop, while Belanger won eight. Keep in mind that Gold Gloves are voted on by each league’s players and managers — those most knowledgeable about other players’ performance.

Thanks David…I like that calculation!

I like to see 100 points difference. Baseball is a game of percentages. Every time a batter comes to the plate the odds are that he will make an out. Any time he doesn’t make an out, he beats the odds. You beat the odds enough times, you win the game.

Nice tribute just published today in NY Daily News. Hopefully, it is accessible to non -subscribers.

https://www.nydailynews.com/2024/01/27/bud-harrelson-leaves-behind-legacy-miracle-mets-alzheimers/