Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

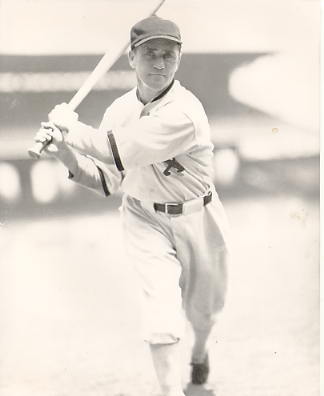

Jocko Conlan Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

It’s No Mystery! Mystery Player Number 5 Is Of Course the Great Hall of Fame Umpire, Jocko Conlan!

From the vast photo archives of Baseball History Comes Alive, we’ve projected a stunning, 10 by 18 foot picture on our auditorium screen. It’s the next mystery baseball great. A collective gasp emanates from a small group of fans, as they take in the image. It’s not the diminutive 5’7” 165 pound physical presence but the overwhelmingly confident, feisty, take charge smile, projecting total control. Mess with this guy at your own risk. He fears nothing.

Ironically, our protagonist got his nickname from another major league player with the same name, but with a single letter changed in the surname. The latter played briefly for the 1923 Boston Braves, as a middle infielder. He was two years older. Both were the same height. Both lived to be 89. There was also a striking resemblance regarding the pair’s physiognomy. The subject of the essay, whom we shall call John, was baffled by the same name moniker that attached to him and admitted, “It was the damnedest thing, but I guess I really did look like him. I’d be stopped on the street and somebody would shout, ‘Hey, John, remember me from graduate school?’ Or, ’Don’t you remember me from Harvard?’ When I’d look at them in disbelief, they thought I was putting them on!”

The Beginning

Born in 1899, and one of nine children whose dad was a Chicago policeman, John grew up as a rabid Chicago White Sox fan with a burning ambition to play for the pale hose. He would realize that dream, briefly, in 1934. His professional baseball career began in 1920 and included nine years at the highest minor league level (designated AA at the time). He played for the Rochester Tribe, Newark Bears, Toledo Mud Hens and Montreal Royals—batting over .300 six times and never lower than .283. John was fast, with a strong left arm and could go get ‘em with the best. He averaged 20 assists a year for several seasons. False modesty was not in his arsenal. While playing for Rochester, he once tracked a ball from centerfield, up a terrace in left-center, scaled wooden boards fronting the fence, whirled and made a lunging one-handed stab—then slid down the wall on his back completing the play. John stated, matter-of-factly, “I don’t believe there has ever been a catch quite like that one.”

Our Mystery Man loved George Stallings who ran the Tribe at the time. Stallings really knew the game. He was tough but fair and presented a handsome, well-dressed image, managing in a business suit instead of a uniform. George appreciated his left-handed centerfielder, even though he lacked power, because John reminded him of his Miracle 1914 Boston Braves players, who came from last place on July fourth to sweep the mighty Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. Stallings never let his players talk to an opposition player. He declared, “You’re here to beat them, not talk to them. If you want to discuss fishing or hunting, talk about it during the off-season. Not here. Not during the season.”

In 1925, Stallings had it set up to give John his major league break. Cincinnati would ship three pretty good players and $17,500 to Rochester for John. But the day before he was to report his left knee freakishly caught the opposing catcher’s shin guard while scoring a run and tore up a gazillion ligaments. It took nine more years for him to make the big leagues. In those days, the majors wouldn’t touch a player with a bad knee (except Joe DiMaggio). John’s knee was perfect the very next year, but no dice. Oh, the vicissitudes of life.

A New Career Blossoms

John was now 35 and in his twilight years as a player. Over two limited campaigns with the Chisox, managed by Jimmy Dykes, he batted .263, produced 96 hits, and drove home 31 runners. Then in 1935, fate moved its huge hand. During a game with the St. Louis Browns, umpire Red Ormsby suffered heat stroke. In those days, only two umpires covered regular season games. Since no other umpire was available, and John had impeccable integrity, he was asked to work the bases. He had a natural feel for the job—positioning and calling plays quickly with authority. Also, he could run faster than most of the players. Rave notices ensued. And, after a few years of minor league seasoning (at $300/month), a wonderful umpiring career spanned a quarter century in the National League, from 1941 through 1965.

John had strong convictions, commanded enormous respect and was unwavering on certain things, particularly checked swings. “To me it was usually crystal clear when a batter swung or didn’t swing. An umpire shouldn’t have to ask for help on the call.” In the early 50s, the field mikes were close to the action and you could sometimes hear stuff you shouldn’t hear. Alvin Dark was batting one afternoon at the Polo Grounds when John was behind the plate and called Alvin out on a checked swing. Clear as a bell, as I watched on TV, Alvin screamed in his high-pitched Oklahoma twang, “G——it, Johnny, ah ‘heeld’ up!”

The Nice and Not So Nice

According to John, umpires loved Rogers Hornsby. Even though The Rajah had a generally surly disposition, he never argued a call. Yogi Berra was known as a constant grumbler. Stan Musial and Gil Hodges were the best (so true, having interviewed Gil at Shea, in 1968). Ted Williams, despite his bad press, was held in high esteem by the umps. John shared, “I called Ted out on strikes in the 1947 All-Star game, batting against Ewell Blackwell. The pitch was too low and I knew I blew it. Williams just put his bat on his shoulder and walked back to the dugout. He never brought up the horrendous call and we had a great relationship.”

“Jackie Robinson was a fierce competitor, tremendous clutch hitter, the best base runner I ever saw. But he used horrible language. I never tolerated abusive name calling directed at me, that’s a sure way to lose respect. One time Jackie thought I missed a play at first. He bellowed from his position at second base, ‘John, you so-and-so, you’re never in position to make a call!’ I said, ‘Well, I’m in the perfect position for you, Mr. Robinson. Get out!’ He could rile me.”

“Leo Durocher was worse. At his best, Leo was the game’s best manager. But you can have him. His mouth was just awful and he complained about every call against his team. I’ve had some experience fighting…and I was ready to knock him out in a game…fortunately, he retreated to the dugout. Not a moment too soon, I might add!”

John praised the skills of black players he saw who never got to the big leagues. “They had marvelous players, those colored teams” he said. “No question, many would have been stars in the majors.”

John Bertrand umpired in five World Series and six All-Star games and was inducted into the HOF in the summer of ‘74, preceded only by Bill Klem and Tommy Connolly, in the arbiter category.

Nattily attired with his blue cap and bow tie, and sporting an outside chest protector, he created an indelible image for those who saw him. His name is…?

Bill Schaefer

Sources: Book: “Jocko,” Jocko Conlan and Robert W. Creamer; Jocko Conlan Wikipedia page; Jocko Conlan, Baseball Reference; Alvin Dark, Baseball Reference

Photo Credits: All from Google search

Subscribe to our website, “Baseball History Comes Alive!” with over 1200 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now closing in on the one million hits mark with 965K hits and over 800 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he