THE BASEBALL HISTORY COMES ALIVE BLOG

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives

October 11, 2022

Today we welcome a guest essay from Matthew Kastel telling us of a 1903 tragedy that changed ballpark construction. It was truly baseball’s deadliest day. From the ruins of Philadelphia’s National League Park emerged modern parks like Shibe, Fenway, and Wrigley. I think you’ll find Matthew’s essay interesting. -GL

Black Saturday – Baseball’s Deadliest Day

The tragedy that changed ballpark construction forever

August 8, 1903

Black Saturday began innocently enough when a 13-year-old girl ran an errand for her aunt that took her past where the Phillies were playing a doubleheader.

1903 was the inaugural year of the World Series, but this was the last thing on the Phillies’ mind. The Phillies were having an abysmal season, and they were playing the equally dreadful Boston Beaneaters (today’s Atlanta Braves) with 10,078 fans in attendance.

While running her errand, Maggie Berry bumped into friends. Fate had them intersect with a pair of drunks while walking in front of what was officially called National League Park, but everyone in town called the stadium Philadelphia Base Ball Park. It was then that the hubris of adolescence and the consequences of inebriation turned lethal.

The group teased the drunks. One of the drunks grabbed Maggie by the hair, stumbled, and fell on top of her. The teens screamed for help, including yelling, “Murder!”

It was 5:40 p.m., and the second game of the doubleheader was knotted at 4-4 when Boston’s Joe Stanley came to the plate. The game halted when a commotion broke out. Fans hearing the cries for help rushed to see what was going on. To get a good view of the fracas 30 feet below, the mob packed a seven-foot-wide balcony that overlooked 15th Street and Lehigh.

Tragedy Strikes

The balcony was intended as a pathway to enter and exit the grandstand and protruded seven feet from a wall that was 14 inches thick. It was estimated 300 people had rushed the balcony. Without warning the balcony broke loose, and over 200 people fell. Sargent Bartlett of the Philadelphia PD told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “You could not tell if they were dead or alive. Timber, rubbish, and bricks were piled everywhere.”

The police responded to the calamity. They commandeered street cars, delivery carriages, and personal vehicles and rushed the victims to the hospital. In the crisis, the best and worst of humanity shined through. Locals opened their homes to victims. Doctors rushed to the scene to give aid, and good Samaritans offered help, best they could.

Others picked the pockets of the dead and wounded. In the ballpark, panic ensued. Sporting Life reported:

“The sound of the breaking timbers and the cry of those caught in the fall gave rise to the belief that the whole stand was about to fall. With a wild cry of fear, the crowd rose and made a rush to the field. They clamored over the seats and over one another, screaming, swearing, striking, and fighting for precedence. In the mad rush for safety, they tore at one another’s clothing and behaved like insane men.”

Players grabbed bats as weapons to keep from getting stampeded by the crowd rushing the field. The game was canceled, never to be made up. The casualty report was 12 dead and 232 injured.

Dead was the Phillies’ mascot, Sammy Kelly, who had the misfortune of standing

on the street below when the balcony fell. Also among the dead was Edward Williamson, a Civil War veteran who until this moment seemed indestructible. He had survived wounds at the Battle of Antietam in 1862 which was the bloodiest day in American history with 22,717 casualties. He had also made it through incarceration at the notorious Confederate prison camp, Andersonville, where 13,000 died from scurvy, diarrhea, dysentery, and neglect.

A grocery store on 15th Street gathered up over 100 hats from the scene and lined them in their store windows, so their owners could claim them. This became a makeshift memorial, as the hat owners were among the deceased, and the injured were in no condition to pick up their hats.

Several versions of the drunken men story had developed and the police wanted to speak with them to discern what happened. The drunks were seen sleeping it off in an alley near 15th Street. By the time the police looked for them, they had sobered up and ambled off, with their identities and version of events lost to history.

Not the First Time…

If Philadelphians thought that the Philadelphia Base Ball Park was cursed, you couldn’t blame them. This was the second Philadelphia Base Ball Park. The first, built on the same site, burned to the ground while the Phillies were to take on the Baltimore Orioles almost nine years to the day of Black Saturday on August 6, 1894.

Not to be beaten, when the first ballpark burned down, $225,000 was invested in what was hoped to be a fireproof facility. It was also the first stadium in the world to use the latest architectural method of cantilever construction. Thanks to the cantilevered concrete supports and iron girders, it eliminated the need for support columns that had made for obstructed viewing.

For its time, the National League Park was a sophisticated building. That it had failed so spectacularly only a few years later must have been a jolt to the baseball community. But disasters often prove to be a clarion call for change. This was certainly the case with Black Saturday.

The Disaster’s Aftermath

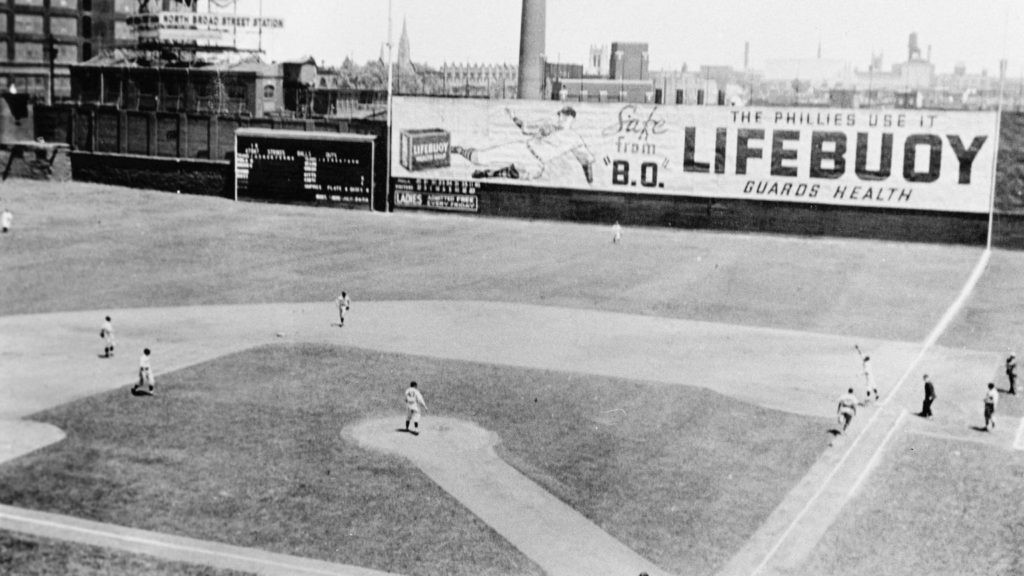

In the aftermath of the disaster, in 1909 two new stadiums opened, Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, and the Phillies’ cross-town rivals in Philadelphia, the Athletics, opened Shibe Park. Gone were the wooden ballparks of yesterday. The new era of baseball stadiums was now constructed out of steel and concrete.

The new ballparks were not only safer, they also came with bells and whistles previously unheard of. Forbes Field was the first ballpark to have elevators and ramps going to the upper deck. It was also among the first to have luxury seating.

Shibe Park took stadium aesthetics to new heights. Fans entered through a façade of brick and arches. The team offices were housed in the spectacular octagonal Beau Arts Tower whose design was reminiscent of the architecture of the French Renaissance.

Shibe Park’s program in 1909 indirectly referenced Black Saturday, touting their new ballpark’s construction.

“Several unfortunate accidents called serious attention to the need of something more durable than wood for the safety of the enormous crowds which thronged parks where winning baseball was being played … In the evolution of building construction, vast strides have been made, and daring builders experimented with various materials to overcome the corrosive influences of time and the elements. Up to the present time, nothing has been contrived which form a more lasting combination than wrought steel and cement. Technically it is known as reinforced concrete … The bleachers and grandstand and walls are solid beds of concrete.”

If you want to experience what this new era of stadiums looked like, you can still visit Fenway Park in Boston (opened in 1912,) home of the Red Sox, and Wrigley Field in Chicago, home of the Cubs (opened in 1914 and originally called Weeghman Park). Both stadiums trace their origins back to Black Saturday.

As for Maggie Berry, the 13-year-old girl at the epicenter of Black Saturday, she later become a mother of four before dying at the age of 82 in 1973. Baseball and the world changed dramatically in her lifetime. The year she died, Mike Schmidt had just finished his rookie season, and in 1971 the Phillies moved into the 56,000-seat Veterans Stadium.

One wonders if Maggie understood the role she played in sparking the revolution in stadium construction.

Matthew Kastel

(Matthew Kastel is the Past President of the Stadium Manager Association and is a stadium manager. In addition, he teaches a stadium and events course at Mt. St. Mary’s University and is co-author of a textbook: Managing Sport Facilities, 4th Edition)

Resources:

Robert D. Warrington’s Baseball’s Deadliest Disaster: Black Saturday in Philadelphia, as published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly

Matt Albertson’s Coroner’s Jury and Bankruptcy: Aftermath of the 1903 Ballpark Horror as published on phillysabr.com

BaseballReference.com

Ancestery.com

Shibe Park Opening Day Program 1909

Subscribe to our website, “Baseball History Comes Alive!” with over 1200 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now closing in on the one million hits mark with 876K hits and over 700 subscribers: www.baseballhistorycomesalive.com

As always, we enjoy reading your comments

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives