Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

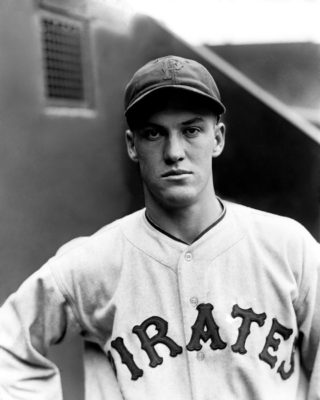

Arky Vaughan Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

We always welcome submissions from our readers, and today we’re happy to publish one from Frank Garland who has written a biography of the great Pittsburgh shortstop, Arky Vaughan. It’s always hard to say a Hall-of-Famer is a “forgotten star,” but I think you’ll agree with me that Arky was a much better ballplayer than most of us realize. So we’re very happy to shine our baseball spotlight on him today. -GL

Another Edition of Baseball’s Forgotten Stars:

Arky Vaughan

Recreating the life of a man born over a century ago is no easy task, and it’s even more daunting when that man has been dead for nearly 70 years. That was the challenge involved in writing the life story of one of the Pittsburgh Pirates’ greatest players – and one of the greatest ever to play in the big leagues: Joseph Floyd “Arky” Vaughan.

As a lifelong baseball – and Pirates – fan, I was aware of Vaughan’s accomplishments. But it was more than just his numbers that prompted me to take a swing at telling Vaughan’s story. He happened to be my father’s favorite player as a kid growing up in Pittsburgh in the 1930s. I never heard that firsthand, as my father died during the magical 1960 season when he was just 33 years old – and I was only 5. But my uncles would tell me later that my dad was a huge Arky fan. So when I went looking for a baseball biography project following the publication of my 2013 biography of Willie Stargell, I trained my sights on the Pirates’ “other” No. 21 – Arky Vaughan.

The Arkansas native, who lived in his native state for less than a year before his family moved to California, wore the Pirates uniform for 10 years, joining the club as a raw 20-year-old rookie in 1932 and holding down the shortstop position – or the “short field” as some called it back in the day – through the 1941 campaign. During that time he never hit below .300 and earned a reputation as one of the fastest – and toughest – competitors in all of baseball. Although quiet off the field, he never backed down on it and had his share of scraps, endearing himself to Pirates fans much like his good buddy, Billy Conn, endeared himself to Pittsburgh boxing aficionados.

Vaughan left Pittsburgh after the 1941 season, as the Pirates – concerned that the looming world war would gut their roster – dealt him to the Brooklyn Dodgers in exchange for four mediocre players. Most would agree that Vaughan is the Pirates’ second-best shortstop of all time, falling behind only Honus Wagner, universally considered the game’s greatest at that position. Some experts rank Vaughan among the top five shortstops all-time and noted baseball historian Bill James had him ranked number two.

Vaughan’s first season in Brooklyn was a disappointment, as he failed to reach the .300 mark, finishing at .277. But he bounced back in 1943, hitting .316 and leading the league in runs scored with 112 and stolen bases with 20. His most memorable moment that season came off the field, though, when he staged a one-man mutiny against Dodgers manager Leo Durocher.

Angered over Durocher’s treatment of pitcher Bobo Newsom, Vaughan removed his uniform in the clubhouse prior to a game with Pittsburgh in mid-July and handed it to Durocher – and then told him what he could do with it before heading for the stands. Dodgers’ president Branch Rickey, who held Vaughan in high regard, talked the veteran infielder into coming down from the stands and returning to the clubhouse. Vaughan did so but did not play that day.

Vaughan finished the 1943 campaign, then chose not to play the next three years, walking away from the game after his age-31 season. To this day, some say it was because he had enough of Durocher, a brash loudmouth who was everything Vaughan was not. Vaughan, though, maintained that he liked playing for Durocher, but that he needed to stay home to run his California cattle ranch, as most of the able-bodied men in that area were serving in the war effort.

After the war, Vaughan did return to the Dodgers for two more seasons – 1947 and ’48. In his first year back, he served as a valuable part-time contributor to the Dodgers’ pennant-winning club, as he batted .325 in 64 games. He finally fulfilled a lifetime dream of playing in a World Series – something that appeared to be a certainty in 1938 with the Pirates before the Cubs’ Gabby Hartnett torpedoed those hopes with his famous “Homer in the Gloamin’.” However, the 35-year-old Vaughan had just three plate appearances in the ’47 Fall Classic; he walked and doubled in two of those appearances as the Dodgers fell in seven games to the Yankees.

He came back for one more season in ‘48 but an assortment of injuries and ailments limited him to just 123 at-bats, and that would be his final big league campaign. He retired from the game for good after a short stint in the Pacific Coast League in 1949. After retiring, Vaughan once more turned his attention to ranching, buying his dream spread in the small town of Eagleville, in the northeast corner of California. There, he spent his days tending his cattle, hunting, and fishing, and occasionally playing cards with the locals. Rarely did he talk about his baseball career; it was ranching and the great outdoors that occupied his thoughts.

Vaughan’s life came to a tragic and untimely end at the age of 40. Just as mystery surrounded his decision to leave the game of baseball at the peak of his career in 1944, plenty of mystery shrouded Vaughan’s death. On the morning of Aug. 30, 1952, after a night of baling hay on his ranch, Vaughan and a friend named Bill Wimer took a small boat out on a high mountain lake to do a little fishing. When Wimer stood up to cast his line, the boat capsized. Conflicting reports filtered in and made it into print. Some said the two men both attempted to swim to shore but went under just 20 feet from their destination. Others said Vaughan – an excellent swimmer – tried to pull the heavyset Wimer to shore but could not make it. Vaughan’s son, Timothy, maintains today that his father, who had been experiencing heart problems, did not drown, but was done in by the frigid water and the high altitude, as the lake sat at about 7,200 feet.

Over Arky Vaughan’s 14-year career, he hit .318 with 96 home runs, 926 RBIs, .859 OPS, and a remarkable .406 on-base percentage. His career OPS+ of 136 places him well above the average of his contemporary players (100 being the major league average). His best year was 1935 when he led the National League in batting average (.385), on-base percentage (.491), slugging (.607), OPS (1.098), and OPS+ (190). He also hit 19 home runs and drove in 99 runs.

In spite of all these accomplishments, it took years before he earned his rightful place in baseball’s Hall of Fame. He finally was inducted in 1985 after a three-person committee that included his oldest child, Patricia Vaughan Johnson, lobbied the Veterans Committee to open Cooperstown’s doors to Vaughan. It was Johnson who gave the induction speech for her father the day he joined baseball’s elite fraternity. She talked about how her father’s dedication and natural talent helped him compile numbers that were too good to ignore. “And because of this, and in his induction into the Hall of Fame, the fame and the glory that he never sought are now his forever,” she said.

Johnson’s unpublished manuscript also provided valuable material for the

Vaughan biography, as Johnson’s daughter, Kathleen Roberts, made that as well as boxes of newspaper and magazine clippings, scrapbooks, photos and other memorabilia available during my research phase of the Vaughan biography project. Among the other materials were several tape recordings that Johnson had made while traveling around and interviewing several of Vaughan’s old teammates, including Dolph Camilli and former Pirate Frankie Gustine.

In the end, all of those nuggets – along with dozens of newspaper and magazine articles – helped bring Vaughan to life for today’s fans to read about and appreciate. Based on everything I heard and read, Vaughan wouldn’t give his own biography much thought. He didn’t seem to put a great deal of importance on his ability to hit a baseball better and more often or run the bases faster than just about any one of his contemporaries in the 1930s. At least he didn’t care to talk about it much.

At heart, he was just a cowboy – and that’s all he ever wanted to be.

Frank Garland