Jackie Robinson’s career as a baseball player and life as a civil rights leader cannot be covered in a single article. Robinson’s life touched so many lives, and still does, that not even a single movie or 20-hour documentary could do it justice. As we celebrate Jackie Robinson integrating the Major Leagues in 1947, let’s look back in a cursory way at what made this man the absolutely right choice to eradicate the color line, and one of the greatest civil rights leaders of the 20th century.

First, the basics: Most people know that Jackie Robinson lettered in four sports at UCLA: baseball, basketball, football and track. What many might not know is that baseball was by far Robinson’s weakest sport. Robinson was All-American in football, All PAC-10 in basketball, set records in track, but batted under .100 in his only season in baseball; he left college before graduation with baseball eligibility left. Robinson was also a champion tennis player and outstanding golfer, so baseball might have been his 6th best sport!

After playing semipro football, and spending time as a lieutenant in the cavalry during World War II, Robinson was signed in 1945 to play for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League. It was evident early that Robinson was a competitor of the highest order. According to teammates on the Monarchs, Robinson argued with umpires during pre-season games that others thought of as mere scrimmages. It soon became clear to all that when Robinson was on the field, he played only one way—all out and to win.

The Monarchs’ regular shortstop, Jesse Williams, was injured in the early part of the ’45 season so Robinson took his place, and although he didn’t have a strong arm, he hit for a high average and for power. He also fought at the drop of a hat against anyone who was dumb enough to challenge him, and he was never on the losing end of a fight. Teammate Newt Allen, one of the best second basemen and shortstops of his era, summed up the rookie Robinson, “He could hit, he was smart, he could bunt, he couldn’t play shortstop.”

Toward the end of the ’45 season, Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey, and his top scout Clyde Sukeforth, chose Robinson to break the color barrier. Of the many players I interviewed over the years, most had the same reaction at the time: they didn’t think Robinson would make it as a Major Leaguer. According to most, Robinson was far from the best player in the Negro Leaguers. Players mentioned stars such as Monte Irvin, Willard Brown, Ted Strong and others as “can’t miss prospects.” Some Negro Leaguers expressed fear that Robinson would fail and it might take years for another player to be given a chance; years later, in hindsight, they all admitted they were wrong!

“I guess I was slightly surprised he was chosen, but Jackie was a good ballplayer,” remembered Indianapolis Clowns and Kansas City Monarchs infielder Sherwood Brewer. “I don’t think anyone envied him for it. He was a great guy, very caring.”

Though Robinson disliked a lot about the Negro Leagues—the segregation, the poor eating and sleeping conditions, the exhausting schedule—he did admire the Negro League players, the men who paved the way for him. “When I look back at what I had to go through in black baseball, I can only marvel at the many black players who stuck it out for years in the Jim Crow leagues because they had nowhere else to go,” said Robinson in retirement.

Despite his limited experience, Robinson, by then 27, tore through the International League with the Montreal Royals in 1946, leading the league in hitting (.349), fielding (.985) as a second baseman, and he led the Royals to the league pennant and Little World Series win against the winners of the American Association.

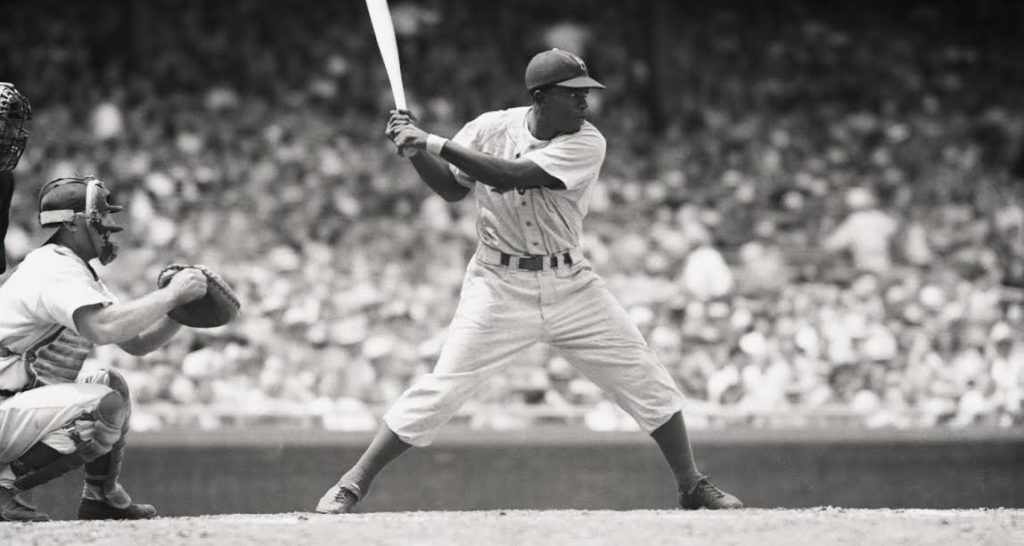

Under extreme pressure and with the weight of the black community on his shoulders, Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers to start the ’47 season as a first baseman. All Robinson did was win the Rookie of the Year Award (the first year it was given out), batted .296 and led the league in sacrifices and stolen bases. Two years later Robinson, by now a second baseman, was the league MVP and the National League batting champion (.342) and started at second in the All-Star Game.

With Robinson on the Dodgers, Brooklyn won pennants in ’47, ’49, ’52, ’53, ’55 and ’56, playing the Yankees in the World Series each year, and winning Brooklyn’s only championship in ’55. Robinson, like Pete Rose, didn’t really care where he played in the field as long as he played and the team won, and Robinson appeared in the World Series as a first baseman, second baseman, third baseman and left fielder.

Through all of his trials and tribulations, Robinson never took a great deal of credit for being the pioneer he was. He always talked about what “we” did. “We” included Branch Rickey, his wife Rachel, his teammates. Above all, Robinson was always a team player. In one of his last interviews, in 1972, Robinson said he was happy at the progress baseball had made, and “we are quite proud in the role that we played.”

After the ’56 season, Robinson was traded to the New York Giants but retired rather than play for his hated rival. During his 10 years in the Majors, Robinson batted .311 with a .409 OB% and .474 slugging%. Robinson was a six time All-Star, led the National League in fielding three times at second base, and, for stats nerds, led the league in WAR for position players three times (’49, ’51, ’52).

When he became eligible for the Hall of Fame, Robinson requested that writers only vote for him based on his playing, without regard to his role as a pioneer; Robinson was voted in on the first ballot.

When I think of Jackie Robinson, the picture that comes to mind is of him stealing home in the ’56 World Series, sliding under Yogi Berra’s tag. Robinson’s steals of home are a great metaphor for his life. I believe that Robinson, who died at age 53, knew he wouldn’t live long due to the pressures of his life, so he never hesitated to right a wrong. In other words, Robinson couldn’t wait for someone else to drive him in; he stole home because he knew that he couldn’t wait! He had to make things happen when he had the opportunity.

I’d like to relate two stories that illustrate what kind of man and leader Jackie Robinson was, and why we still honor him today. The first story takes place in 1945 while Robinson was a member of the Kansas City Monarchs. Over the years, the Monarchs always stopped at a certain gas station when traveling in their bus through Oklahoma. The owner was a nice man, always washed the windows, checked the oil, and gave the players free bottles of pop. He did not, however, allow the players to use the restroom.

In 1945, the Monarchs stopped at the gas station, the owner started filling the tank, and Jackie Robinson got out of the bus and headed toward the bathroom….until he was told that he was not allowed to use the bathroom. Robinson looked toward his teammates on the bus, and one of them explained, “Jackie, we should have told you. We’re not allowed to use the restroom. It’s no big deal. We’ll use one down the road.”

Steaming mad, Robinson told the owner of the gas station to stop pumping the gas. “Either we’re allowed to use the restroom or we’ll never buy gas from you again. I’ll push this bus to the next gas station myself if I have to.”

With the sale of a hundred gallons of gas on the line, the owner relented. Members of the Monarchs looked at each other and one exclaimed, “why didn’t we ever think of that?”

The last story shows what kind of competitor Robinson was. It occurred in 1949 when Don Newcombe, a 6’-4”, 220 pound pitcher was on the mound for the Brooklyn Dodgers. For people new to baseball, a starting pitcher needs to pitch at least five innings to be credited with a victory. Newcombe was pitching a game in the fourth inning, with his Dodgers up 8-0, when he started “coasting” a bit and gave up a run and loaded the bases. Robinson, playing second base, called timeout and went to the mound. As Newcombe tells the story, Robinson started berating the pitcher, accusing him of not giving his all.

“You know what’s gonna happen?” said Robinson. “You keep pitching like this and you’ll end up getting pulled and you won’t get the win! Don’t ever come on this field if you’re not going to give a full effort!”

Newcombe was furious! “How dare he question my effort!” he thought. “When we get back to the dugout, I’m going to kick his butt!” Then, Newcombe recalled, clarity set in. “I thought about it and realized, ‘Jackie would kill me in a fight!’” Newcombe remembered. “And he’s right. I was coasting.” Newcombe struck out the next two batters to get out of the inning and finished the game, getting the win. Newcombe never coasted on the field again, and Robinson is his hero to this day.

One Negro Leaguer I interviewed, Atlanta Black Crackers outfielder Norman Lumpkin, didn’t hide his affection for Robinson, stating, “Vince Coleman made a remark in ’90. Fella asked him what he thought about Jackie Robinson’s part in making it possible for him to make millions of dollars. He said, ‘Damn, he didn’t have no time to think about no Jackie Robinson. He had his own business to think about.’ That would have been the time I’d still be in jail for killin’ him. I would have done some harm to him. Because if it wasn’t for Robinson he wouldn’t even have been there!” Though Robinson’s integration of the Majors eventually broke up the Negro Leagues, Negro Leaguer players admired the way he performed and the support he gave them over the years, helping many get jobs outside baseball.

After retirement from baseball, Robinson worked for Chock Full o’ Nuts, for a black-owned bank, for a black and white owned construction company, and spent thousands of hours working on solutions for what he considered the worst problem in the U.S., the drug problem among young people.

Cheers to a man’s man, the greatest athlete of the 20th century, the greatest competitor in baseball history, and a man who impacted all sports more than we’ll ever know.

“A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.” –Jackie Robinson

-Kyle McNary