Panoramic Photo Above:

Forbes Field, Pittsburgh

Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked As a Top Five Website by Feedspot Among All Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

(Check out Feedspot's list of the Top 35 Baseball History websites and blogs)

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome! Click for details

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Today we welcome the first guest submission from our loyal reader, Thomas Marshall. Tom has become our “go-to-guy” for all things umpire-related! In this two-part series, Tom tell us that umpire hand signals found their origin in accommodating deaf players in the mid-eighteenth century. I enjoyed Tom’s trip through this bit of baseball history and I think you will too! -GL

A Historical Look at Umpire Signals and Deaf MLB Players

I retired from 29 years of umpiring youth and high school baseball, and whenever I watch a game, I pay just as much attention to the “Third Team” as I do the action of the players. I love watching any baseball game on TV, but I enjoy being in a stadium the most, where I can observe the actions of the umpires. After each play, we look to the umpire’s signal to learn the call. Ever wonder how and why those signals got started?

Most baseball fans are familiar with the most common physical signals and/or gestures of the umpires: Out, safe, fair ball, foul, time, strike, ball, etc. There are also many more not-so-common ones, such as foul tip, un-caught third strike, obstruction, and interference. Umpire crews also utilize their own signals to indicate such things as a potential time play, rotations, and the infield fly rule. These are done discreetly, hardly ever noticed by players, coaches or fans. Recently, to enforce the new rules (step-offs, pitch clock, batter timeouts, etc.) the umpires have had to incorporate even newer signals.

Some may find it hard to believe, but there was a time during the genesis of baseball when umpires used no hand or arm signals. The decisions and rulings were all done vocally.

History tells us that baseball began to be played in the United States with increasing regularity during the Civil War. In the various schools for the deaf in existence at that time, the teachers at these schools believed that athletics should be an important part of their curriculum, including baseball. In 1865, Parley Pratt was a deaf teacher and umpire/coach who taught his students baseball at the Columbus, Ohio Institute for the Deaf. Pratt used common gestures of American Sign Language (ASL) in officiating his students’ games. For example, a common deaf sign for “get rid of it”, or “no good” was to extend the right hand, as in a handshake, with the thumb extended upward, and then thrusting the hand over the right shoulder. Pratt used that gesture to signal “out,” the beginning of the traditional “out” signal that we know today.

As for the safe signal, when something was “free,” or “not-to-worry,” the deaf sign was to extend both arms out in front of your midsection, with palms down, and then cross your hands over each other back and forth. This evolved into today’s “safe” signal.

Soon after the formation of the National League in 1876, the first professional deaf player was pitcher Ed “Dummy” Dundon, who had a short, two-year career with the Columbus Buckeyes (1883-84). Dundon had learned the umpire signals from Pratt while a student at the Ohio Institute.

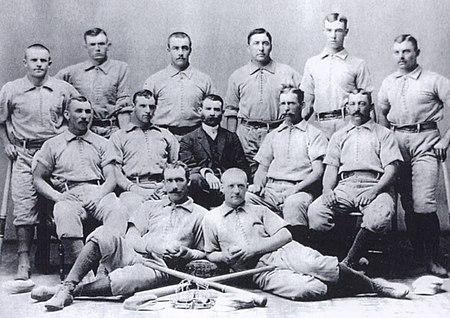

The team from the Ohio Institute initially played sandlot ball. Eventually, it expanded into a semi-pro touring team known as the “Ohio Independents,” playing against other deaf (and also hearing) teams. In 1879, the Independents toured some 3,5000 miles, playing other semi-pro teams, compiling a 44-7 record.

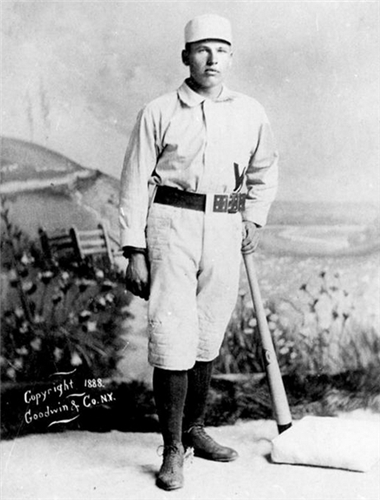

Hand signals were later adapted in 1901 by the Chicago White Sox of the newly-formed American League for the benefit of their deaf player, William “Dummy” Hoy. He had been a student at the Ohio Institute and learned baseball-related signals from Coach Pratt and Dummy Dundon. Hoy played center field for eight major league teams (1888-1902) and taught ASL to as many of his teammates and coaches.

Early in his career, pitchers regularly tried to “quick-pitch” Dummy as he was looking back behind him at the umpire to see whether the pitch was a ball or strike. His batting average suffered as a result. Eventually, it became less difficult for him if his third base coach gave him the ball-strike signal. A quick glance to third base without having to turn his head around made it much easier. The first year after using this method, his batting average improved to .367!

(To be continued…)

Tom Marshall

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with 1,120,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Information: Excerpts edited from

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/t/taylodu01.shtml

The picture you have in the New York Giants uniform is not “Dummy”

Hoy but Luther “Dummy” Taylor.

Today, we deem the common nickname for a deaf player, i;e; Dummy to be highly reprehensible and pejorative.

Obviously it wasn’t in the 1800s and early 1900s.

Thanks, it’s been corrected.

Thank you, Thomas! Your account, written from the perspective of a former umpire, is an excellent reminder that we can “observe a lot by watching,” as another wag behind the plate once said.

In your follow-up essay, you might mention the circumstances under which most umps rely on their hand-signals only, rather than supplementing (or substituting) them with audible calls of one sort or other. I vividly remember the day that Harmon Killebrew, anchoring third base for the old Washington Senators/Nationals (n.b., Dr. Livacari) at Griffith Stadium in the 1950s, speared a one-hopper right next to the bag, then took the time to turn and check the umpire for a visual sign before deciding whether to hold the (foul) ball or give the (fair) ball serious gasoline in time to nip the runner across the diamond. Luckily that ump, who said exactly nothing on the play, was pointing emphatically into fair territory, and so Harmon instantly turned back and fired the ball to first as the home-town fans cheered in appreciative amazement. But why did Killebrew have to look? Why, if you care to make an educated guess, did that umpire rely strictly on a gesture — especially one the fielder couldn’t see without looking around — when crying “fair ball!” was so clearly a better option?

You have shown up just in time, Dr. Marshall! (The question has been bugging me for 65 years.)

May I say it? “Play ball!”

Best regards,

Michael

Michael – “Fair ball” sounds too much like “Foul ball”. Any umpire who verbalises “fair ball” shouldn’t be allowed within 5 miles of a ballpark. Sometimes the noise of the crowd is such that an audible call can’t be heard which is why Killebrew would have checked the signal – but I’m wondering why he checked at all as this would have given the batter-runner a higher probability of reaching base than just throwing the ball in the first place.

Thanks Michel, intersting observations…Happy Thanksgiving!

Senor Keedy….reader “Simon” replied correctly. Any experienced umpire should know that a ball determined to be foul is declared with both a physical signal and the ONE word vocalization of : “FOUL”. No vocal should be uttered for a ball determined to be FAIR. BTW, love the mention of of one of those “Yogi-isms” ! “Killer” was an appropriate nick-name for Killebrew {I remember when he used to “kill” the WSox}. And yes….”PLAY BALL” ! Thnx, sir.

Very, very interesting and well done story. Thanks for relating the origin of umpire signals – Entirely new to me!

Thanks jay! Happy Thanksgiving!

Interesting and informative. I’ve been a fan 70 (+ -) years and it never occurred to me to even wonder at the origin of umpire signals. I’m always impressed when I learn, after the fact, that the umpire crew had signaled to be heads-up for a tagging runner or potential wheel play with a runner on second.

I read long ago that Dummy Hoy and his wife (also deaf) had lived in a house in Cleveland with a special system for letting them know someone was at the door. Rather than knocking or ringing a doorbell (which neither would have heard) there was a lever on the door’s exterior. Flipping it would drop a marble or ball bearing onto the wood floor. The Hoy couple went about their home in stocking feet, and thus were able to “feel” the vibration on the wooden floors and know visitors were outside.

Thanks for checking in, Tom…Interesting information!

Signals are even more vital when you’re working in a two-umpire crew. Part of the pre-game meeting covers signals. Usually umpires use the same 1st-and-3rd and Timing Play signals – but as long as the crew knows what each other is doing (there’s nothing worse than conflicting calls for the same play!), it really doesn’t matter as to specific signs you use (and a lot of baseball umpires also umpire softball, which is MUCH MUCH more hierarchical and inflexible).

The story goes that the football huddle was invented by deaf students at Galluadet University so that the opposition could not see their hand signals, although I never understood why a huddle would not be equally effective in shielding verbal play calling. Gallaudet uses a drum beat to count the cadence before the snap. The players can’t hear the drum, but they can feel the vibrations. I suspect the same technique can be utilized for ball/strike calls for a deaf baseball player.