Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

While speaking to a group of children about the Negro Leagues, a young girl asked 80-year-old John “Buck” O’Neil, “What did you do after baseball?”

“After baseball?” O’Neil replied. “Young lady, there is no AFTER baseball. It’s always baseball!” For almost 94 years, Buck O’Neil was all about baseball!

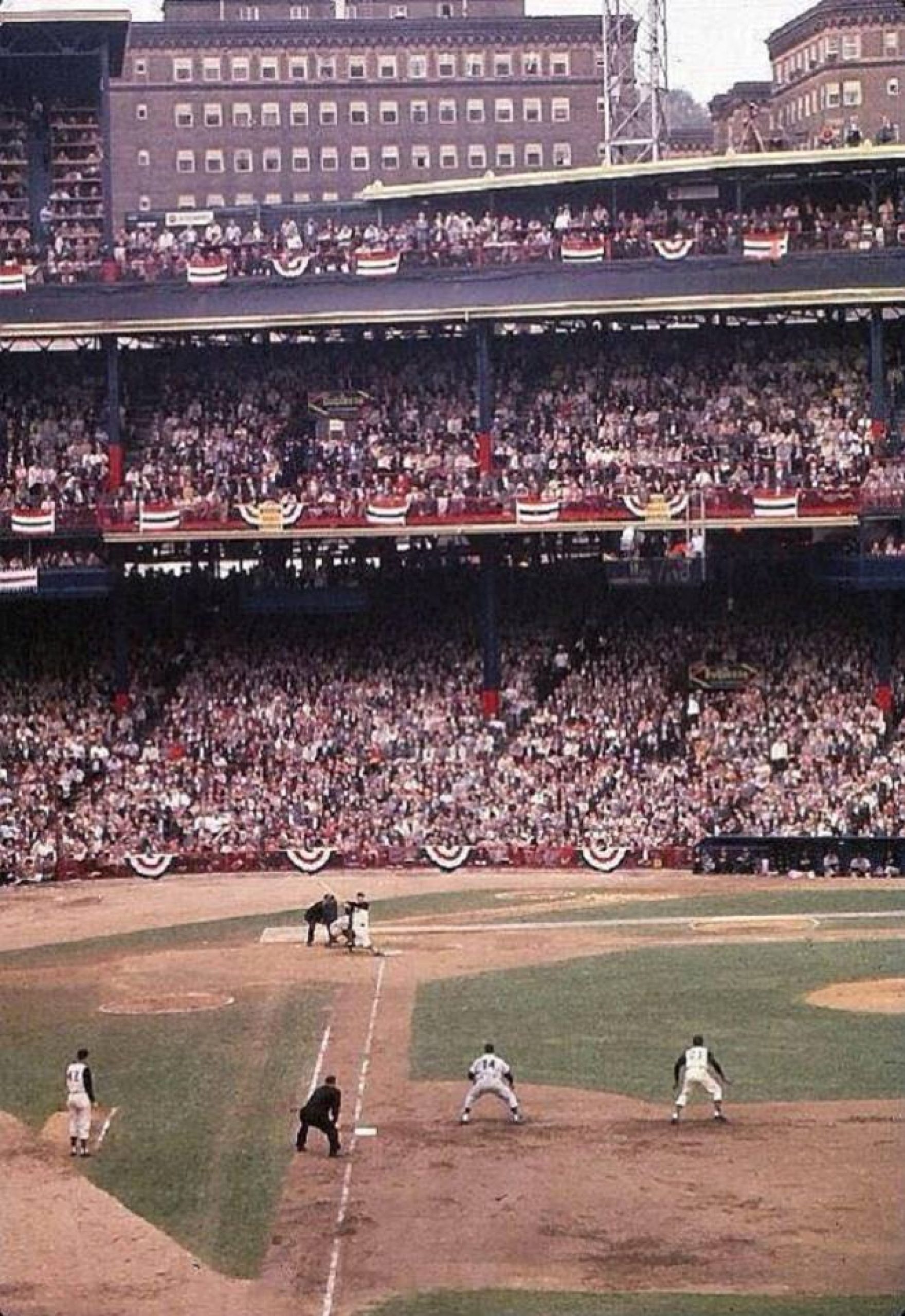

In the 1930s, two first basemen named “Buck” made the big time in black baseball: Buck Leonard and Buck O’Neil. For years Leonard was a fixture with the Homestead Grays and O’Neil with the Kansas City Monarchs.

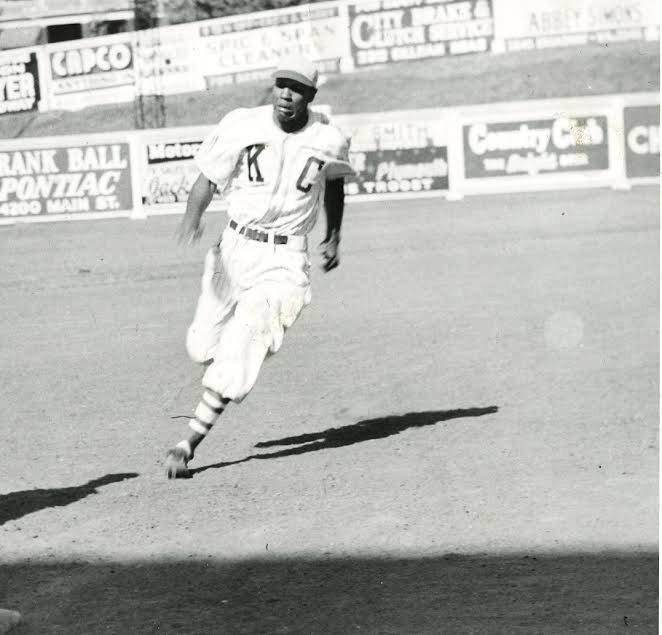

Although Hall of Famer Buck Leonard was the best first baseman of the 1930s and 40s, Buck O’Neil was a star in his own right. A much bigger man, physically, than Leonard, O’Neil (6’-2”, 200) was not a home run hitter, but a slick-fielding line-drive hitter along the lines of a right-handed throwing and hitting Mark Grace.

O’Neil was born in Florida and grew up watching and helping his father work in the celery farms. O’Neil vowed to make a better life for himself and, with his father’s blessing, he left the farm in search of his dream of playing baseball. For two years O’Neil attended Edward Waters College in Jacksonville where he starred on the baseball team, and started his professional baseball career with the Miami Giants, a team owned by a man named Buck O’Neal, whose nickname he was bequeathed.

In 1935, O’Neil was the first baseman for the Denver White Elephants, along with fading superstar Oliver Marcelle, and the team entered the first National Semipro Tournament in Wichita, Kansas. It was in Wichita that O’Neil caught his first glimpse of top Negro League players when the Bismarck integrated team stormed through the tournament with Satchel Paige, Double Duty Radcliffe, Quincy Trouppe, Hilton Smith, Barney Morris and Chet Brewer to win the $5,000 first prize. The White Elephants team barely made enough money to have a good time in Wichita before going home.

In 1936, O’Neil played with the Dunseith, North Dakota Acme Colored Giants, and batted over .300. The Acme Giants boasted future Negro League stars Johnny Markum and Joe Scott, and. after playing a few months in North Dakota and Minnesota, the Dunseith Giants changed their team name to the Shreveport Acme Giants and barnstormed south.

In 1937, O’Neil started the season with the Zulu Cannibal Giants, where he was required to wear makeup and a grass skirt! O’Neil didn’t like the “clowning” that went with playing for the Giants, and jumped to the Memphis Red Sox who were managed by Double Duty Radcliffe. Memphis already had Goose Tatum at first base, so O’Neil was eventually traded to the Kansas City Monarchs where he would stay for almost 20 years as a player and manager.

O’Neil was a great contact hitter and usually batted in the #2 slot in the batting order because of his ability to hit-and-run and push the ball to the right side of the infield to move up runners. He also spent plenty of time in the 4th, 5th and 6th spots because of his ability to drive in runs. When he was young, O’Neil could run, and in 1938 he came in second in the Negro American League in stolen bases.

In ’42, O’Neil helped the Monarchs win the Negro American League pennant, and he batted .353 in the World Series that fall as the Monarchs swept the Homestead Grays. O’Neil showcased his diverse skills during the series with two booming triples as well as a well-placed bunt single.

It was while playing with Satchel Paige on the Monarchs that O’Neil received a second nickname that only Paige addressed him by: Nancy. According to O’Neil, the Monarchs were staying at a hotel when Satchel snuck out of the room he was sharing with his wife in order to meet up with a girlfriend named Nancy. Paige was whispering for Nancy outside her room when both Paige’s wife and Buck came out of their rooms and saw Paige. Without missing a beat, the fast-thinking Paige turned to Buck and said, “There you are, Nancy! I was looking for you!” Until Paige died, he always addressed O’Neil as Nancy!

O’Neil missed several seasons (1943-‘45) serving in the Navy during World War II, and missed playing with Jackie Robinson with the Monarchs in ’45.

Like Mark Grace, O’Neil hit the ball hard to the opposite field, and in 1946 he copped the Negro American League batting title with a .353 mark. In the Negro League World Series that same year O’Neil batted .333 with two homers (including a 7th inning blast in game 7) in a losing effort against the Newark Eagles, and was robbed of a triple late in the seventh game by Leon Day (the great pitcher was playing center field) that could have meant the Championship for Kansas City.

That winter, O’Neil played with Almendares in the Cuban Winter League, and they swept Havana three straight games to end the season and win the pennant.

O’Neil recalled years later, “Whew, they turned it out. Everybody was excited. They had people riding all over the streets in cars, hanging onto streetcars, blowing horns, with ribbons and banners and everything. Oh, Havana was outstanding!”

In 1948, Frank Duncan retired as manager of the Monarchs, and O’Neil was named his replacement. He would manage the Monarchs through 1955.

Besides being an All-Star player, O’Neil may have been the best Negro League manager of the 1940s and 50s. He sent more players to the Majors than any other manager, including Elston Howard, Ernie Banks and Gene Baker. Players remembered O’Neil’s managing style as “always encouraging” and “a player’s manager.”

Though Negro League statistics for many of O’Neil’s seasons are incomplete, in 1952, when O’Neil was 40 years old, he led the league in fielding percentage at .988, and was 12th in batting with a .333 average, with 12 doubles, one triple, five homers and 37 RBIs in 171 at bats; in a full Major League season of 550 at bats, those numbers would extrapolate to about 183 hits, 39 doubles, 16 homers and 119 RBIs.

O’Neil played in four East-West All-Star games failing to hit safely in 11 at bats, but garnered a sacrifice and RBI. He also managed the West squad in ’49 and ’50 and ’53, and was named manager in ’51 but was replaced due to illness. In his three East-West games as manager, O’Neil’s team won twice.

In 1956, O’Neil was hired as a scout with the Chicago Cubs and he was responsible for scouting and signing Lou Brock. In 1962 he became the first black coach in Major League history when he suited up for the Cubs. Years later, O’Neil scouted with the Kansas City Royals and in 1998 he was named “Midwest Scout of the Year.”

Most baseball fans know O’Neil as one of the stars of Ken Burns’ “Baseball” documentary, and he achieved much more fame as an ambassador of the Negro Leagues than as a player. O’Neil was a wonderful speaker, and had a great motto on life that he shared often: “Always stop and watch pretty women in red dresses walk by!”

Because of his playing, managing, coaching in the Majors, working as a scout, and promoting the game, he should get serious consideration for enshrinement into the Hall of Fame.

He barely missed being inducted in 2006, but in his usual classy manner Buck looked at the bright side. According to the Kansas City Star, O’Neil reasoned: “God’s been good to me. They didn’t think Buck was good enough to be in the Hall of Fame. That’s the way they thought about it and that’s the way it is, so we’re going to live with that. Now, if I’m a Hall of Famer for you, that’s all right with me. Just keep loving old Buck. Don’t weep for Buck. No, man, be happy, be thankful!”

In 2006, O’Neil, 94 years and eight months old, signed a contract with the Kansas City T-Bones of the Northern League (independent Minor League) and drew a walk, making him the oldest player in professional baseball history to make a plate appearance in a game.

O’Neil died on October 6th of 2006, and on December 7th O’Neil was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush, joining athletes such as Jesse Owens and Jackie Robinson in receiving the United States’ highest civilian honor.

-Kyle McNary (http://