Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Today we welcome back Thomas Marshall with an interesting account of an ugly incident in American history. If ever a silver lining can be found in such an incident as this, it was that it led to certain Leavenworth inmates eventually playing in the Negro Leagues. I think you’ll find Tom’s essay interesting. -GL

An Unlikely Path To The Negro Leagues

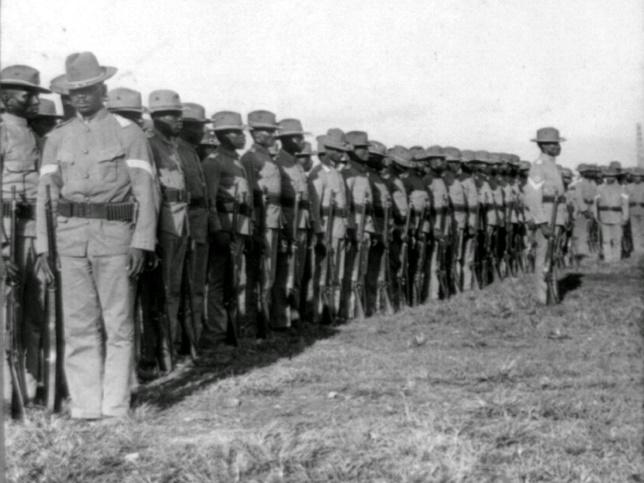

In 1917, near the beginning of the U.S. involvement in WWI, the United States Army sent 156 African-Americans from the 24th Infantry Regiment’s “Buffalo Soldiers” to Houston, TX to assist with the construction of Camp Logan. Soon thereafter, due to their unwanted presence in the area, and the “Jim Crow” policies of the time, these men experienced hostility from the all-white Houston police department and white residents. Escalating racial tension led to the arrest and beating of a few black soldiers who gathered in a black section of Houston. Retreating from police gunfire, two soldiers escaped by hiding in a nearby house. Not finding them, police instead arrested a black female living in the house and severely beat her. On August 23, 1917, those incidents erupted into a riot (the “Camp Logan Mutiny”) that saw 118 armed soldiers march into downtown Houston, shooting and killing 5 policemen and 11 civilians (five Buffalo Soldiers were also killed). All 118 soldiers were court-martialed. In a 1918 military hearing, by an all-white 13-member judicial panel, 110 were convicted. Of those, 64 received life sentences and 19 were executed. The rest received sentences of 30 months. The incarcerated were sent to the U.S. Federal Penitentiary at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

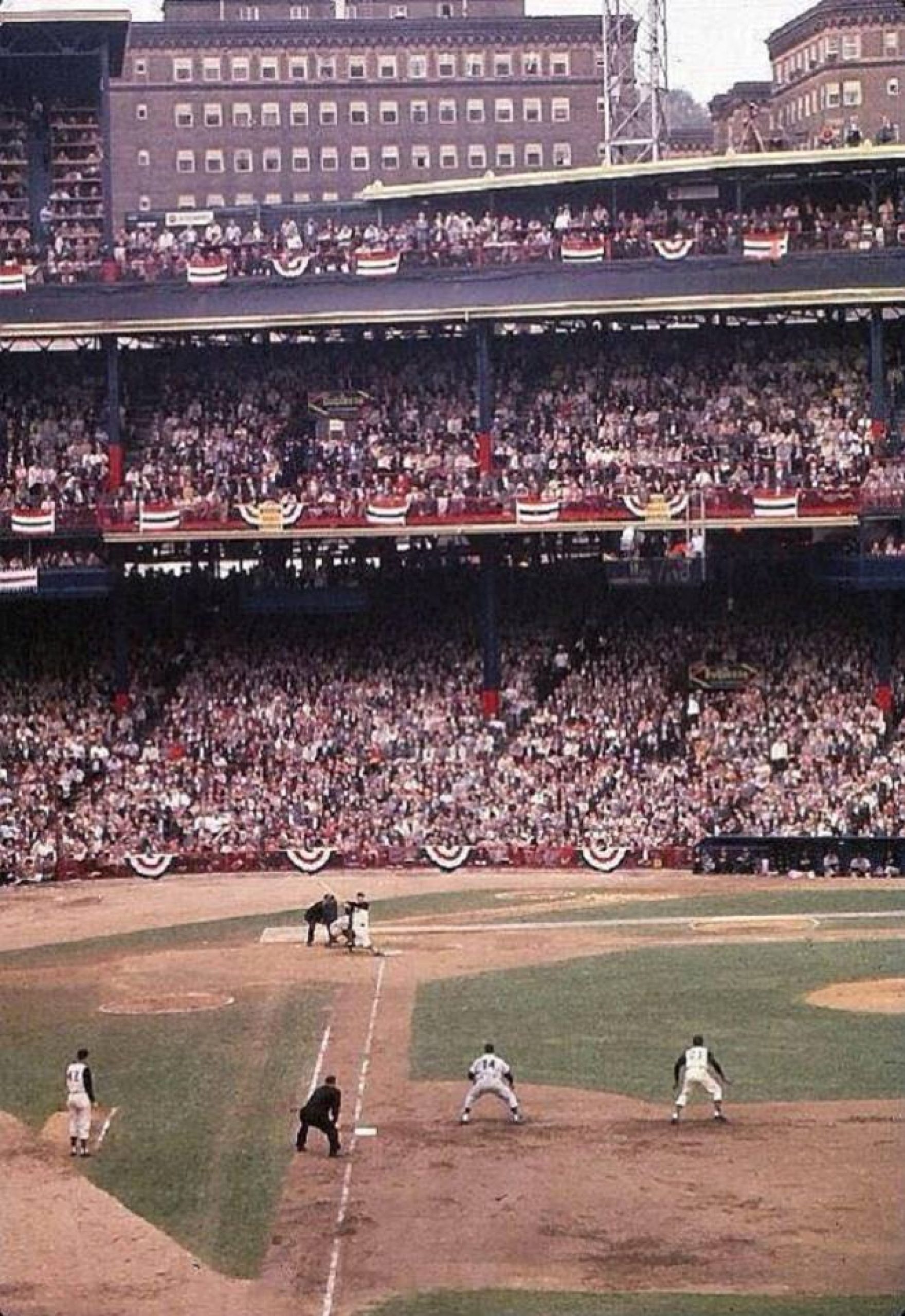

In the late 19th Century, many U.S. prison wardens suggested that to promote exercise, encourage proper behavior, and be a stress release from the monotony of confinement, inmates should play sports. Beginning in 1912, Leavenworth Penitentiary Warden R.W. McCaughry began to form baseball teams. A prison stadium was constructed (see featured photo) with a seating capacity of 1,500. Initially, there were three teams The “Brown Sox” (Caucasian prisoners), the “Red Men” (Native Americans), and the “Booker T’s” (Black inmates). Most of the credit for starting the Leavenworth baseball program can go to Leavenworth inmate William Wilson, who after an up and down major league career (1890, 1897-‘98) in the Federal League, had turned to a life of crime. While imprisoned, Wilson taught the finer skills of baseball to his fellow prisoners. The Booker T’s dominated play, totally over-matching the other two teams. In 1913, the Brown Sox won only one game, despite having two very skilled players: Joe White (who had played semi-pro baseball in New York), and Danny Claire, a veteran of seven minor league seasons (Texas, Western & Pacific Coast Leagues). For the Red Men and Brown Sox (especially), the constant losses created so much hatred and racial animosity against the Booker T’s, that the baseball program was almost canceled. To save the program, in 1914 the Booker T’s schedule was expanded to play other penal institutions, military teams, semi-pro and town teams in Kansas, Oklahoma, and northeast Texas. Still, the Booker T’s were dominant. From 1914 to 1922 they were 130-65.

During this time of playing many other different teams, the racial tension was still commonplace, and the Booker T’s continued to receive abuse from opposing players and fans. In an attempt to minimize perceived bias, one black umpire and one white umpire were used. One of the umpires at the Leavenworth games was Albert Felt; himself an inmate, who was once the President of the Minor League Class “D”, Nebraska State League. In 1922, the Kansas City Monarchs came to Leavenworth to play the Booker T’s in a 7-inning exhibition game. Many expected to witness a complete annihilation of the Booker T’s by the highly skilled and polished Monarchs, but the Booker T’s played admirably, losing 10-4.

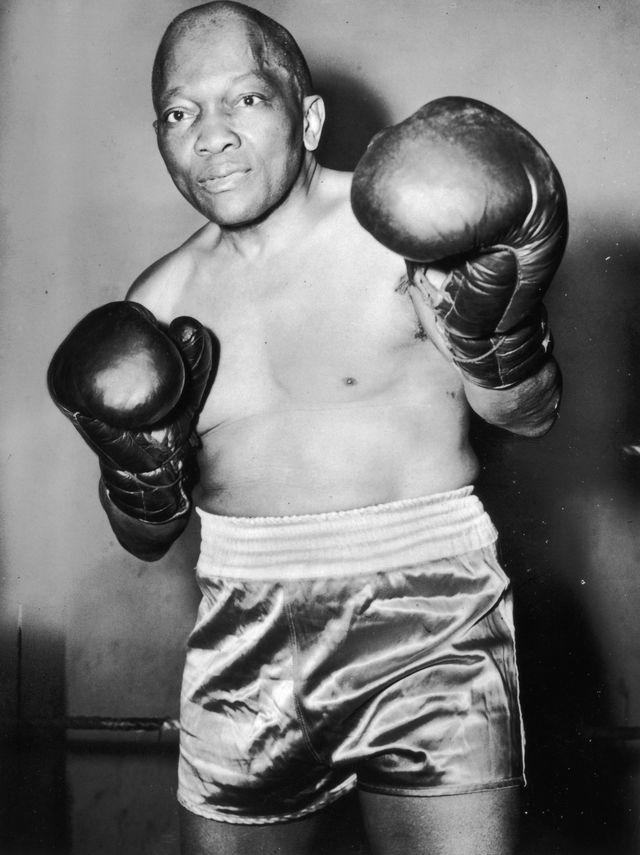

Jack Johnson, the famous heavyweight boxer, grew up in Galveston, Texas, and in

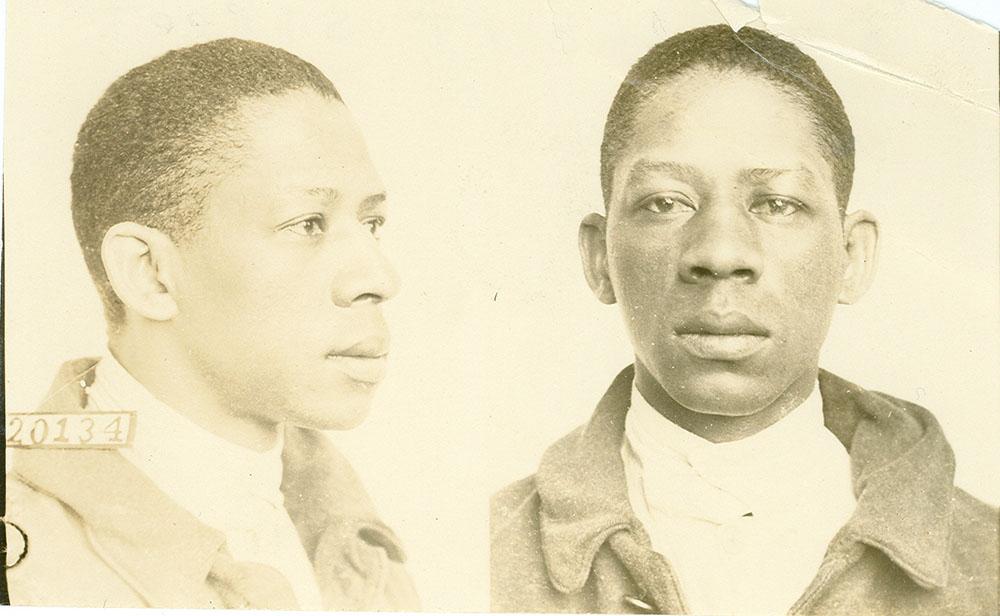

his youth, loved playing baseball almost as much as boxing. In 1913, he was convicted of violating the Mann Act (a human trafficking offense). While awaiting sentencing, he skipped bail, and while posing as a member of a black traveling baseball team, fled to Canada, then Mexico. In July, 1920, after seven-plus years as a fugitive, he surrendered to federal agents, and was sentenced (by future MLB Commissioner Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis) to Leavenworth Penitentiary for two years. While serving his time at Leavenworth, he began to watch baseball games played there and even umpired some of them. Because of their shared love of both boxing and baseball, Johnson had formed a close friendship with Rube Foster, the Negro League pioneer and owner of the Chicago American Giants. After being paroled in 1921, he told Foster that while at Leavenworth he had seen four fellow inmates who he thought had the ability to play in The Negro League. Three of them had committed crimes not affiliated with the Houston riot: Albert Street, David Wingfield, and Joe Fleet all had brief “cup-of-coffee” appearances in the Negro League, playing sporadically during the 1925 season.

The very best player on the Booker T’s had been outfielder Roy Tyler. As a Buffalo Soldier, he had been a participant in the Houston riot, but in a very minor capacity. In 1924, it was agreed upon by authorities that he be paroled to the custody and supervision of Rube Foster. In two seasons playing with Foster’s Giants (1925 and ‘26), Tyler played superbly on defense and hit .301. He then spent the 1926 and ’27 seasons with the St. Louis Stars and Cleveland Elites. Unfortunately, in 1928, Tyler violated the terms of his parole and was incarcerated once again. First sent to the Indiana State Reformatory, and then back to Leavenworth. He finally was released in 1936. After that, Roy Tyler never played another game of baseball. He died in Kalamazoo, Michigan in 1984 at age 84.

What are the odds that four men could emerge from the dreary, hard, forsaken existence of being incarcerated in a federal prison, to experience the unlikely opportunity to play shoulder-to-shoulder with some of the best ballplayers on the planet? Kudos to Jack Johnson for his recommendation to Rube Foster…..it made something that was very “unlikely” become a reality.

“PLAY BAL!”

Thomas Marshall

Sources:

Thos. Rives, National Archives

Robert Rives, Wichita St. Univ.

The Leavenworth Times

Kansas City Star

Chicago Defender

J.A. Riley, Biographical Encyclopedia of Negro Baseball League

Bill Lamb, S.A.B.R.

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with over 1,168,000 hits and over 950 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Meticulously researched and interesting, Tom. You’re one of the great fans!