Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Scroll Down to Read Today’s Essay

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates. As a Free Bonus, you’ll get instant access to my Special Report: Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

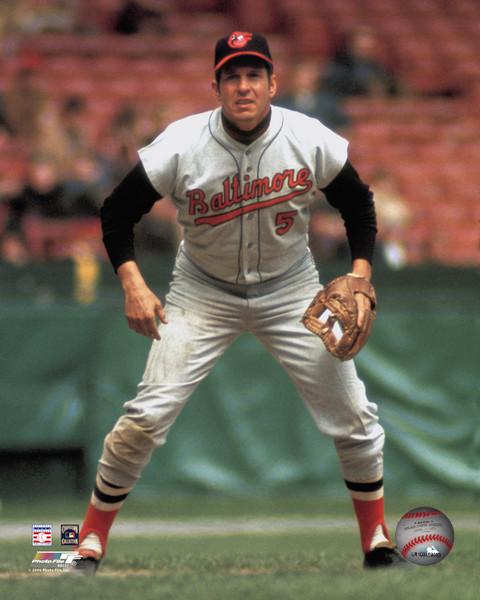

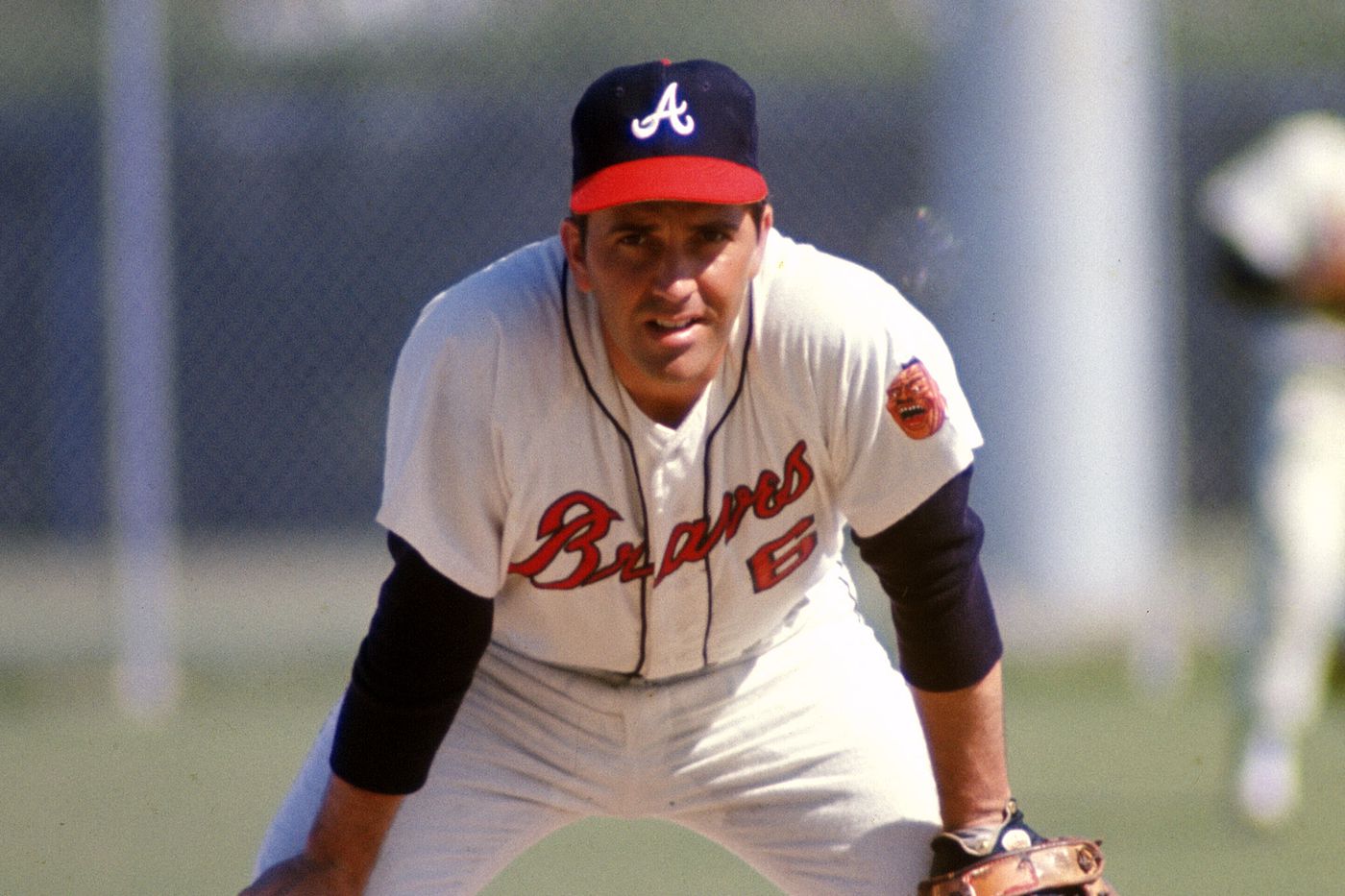

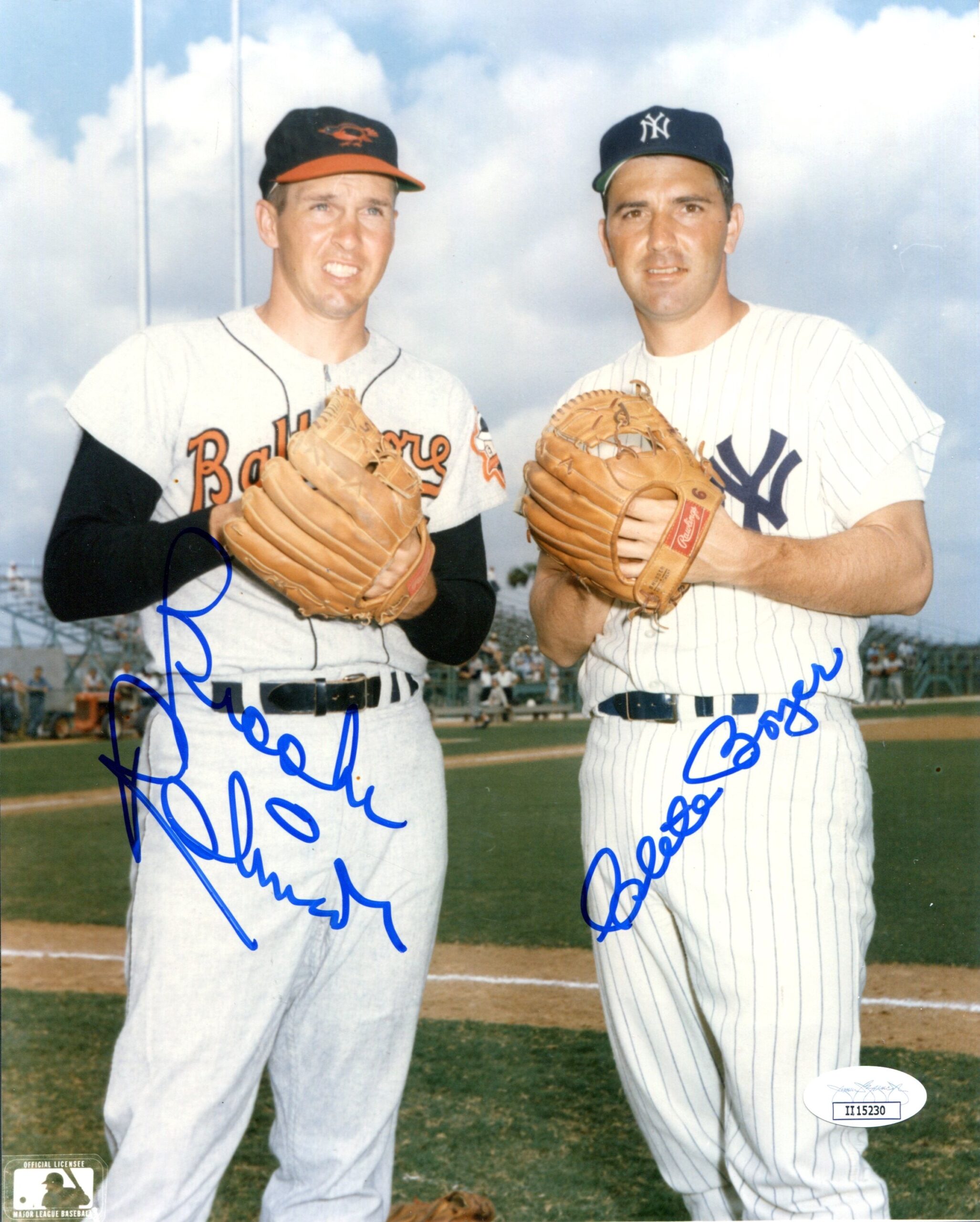

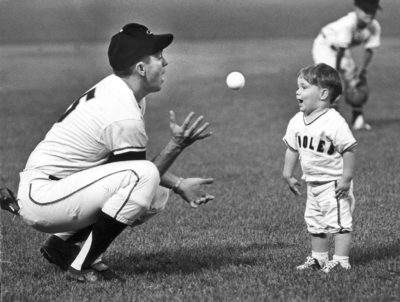

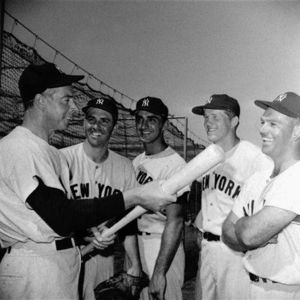

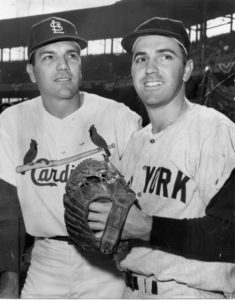

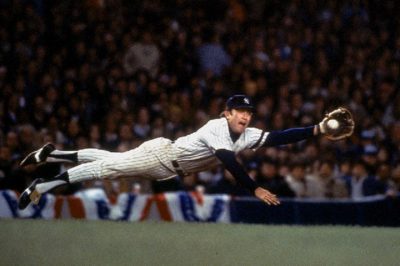

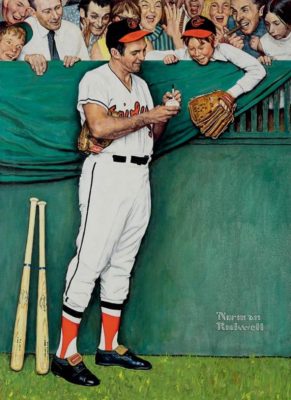

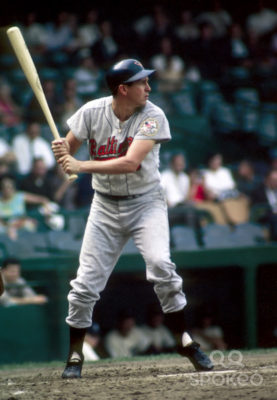

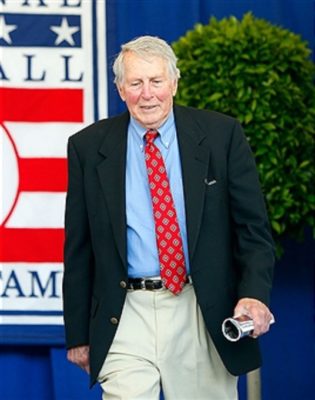

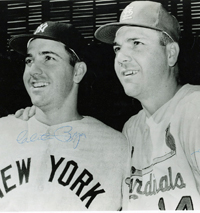

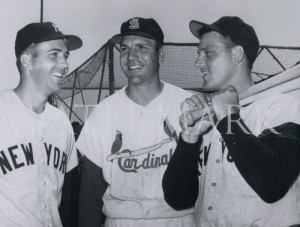

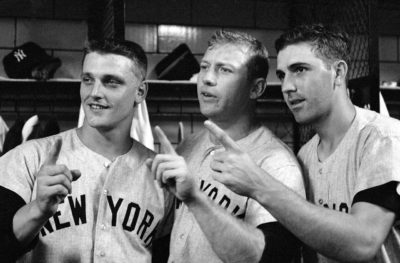

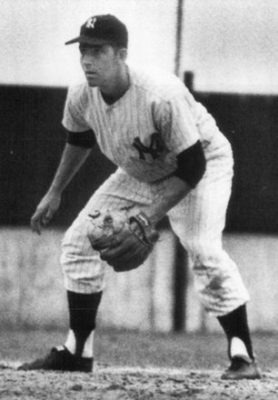

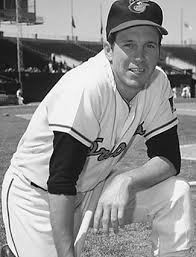

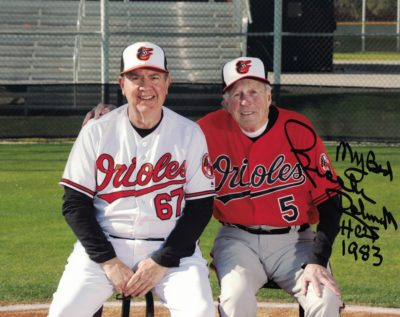

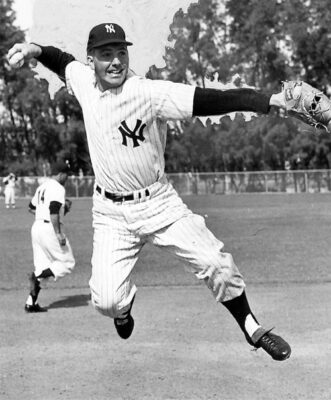

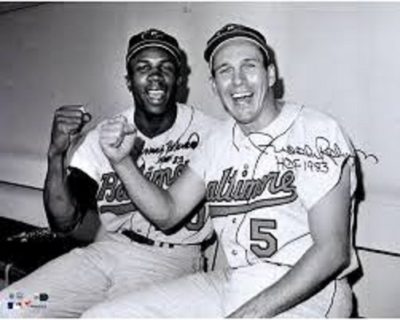

Brooks and Clete Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Today we welcome back Vince Jankoski with another thought-provoking essay, asking the question: Who was a better fielder, Brooks Robinson or Clete Boyer? I’m starting to realize that Vince is a guy after my own heart: He likes to think “outside the box,” and doesn’t necessarily accept the conventional wisdom. And he always does his homework when making his case. Certainly, his essays on Yankee-Kansas City trades fit that description. I know that not everyone will agree with Vince’s conclusions, but I’m glad to give him a forum to voice his well-formed opinions; so I hope you will take the time to read what Vince has to say. Feel free to disagree as forcefully as you’d like. That’s what makes baseball history all so interesting! -GL

Who Was the Better Third Baseman,

Brooks or Clete?

Ken Iglehart of Baltimore Magazine once wrote: “For at least a century, Baltimore has had something of an inferiority complex.” Baltimore is not New York. It is not D.C. It is not even Philadelphia. It is sort of like Detroit on the Chesapeake. Baltimore has crime, poverty, and deteriorating neighborhoods. On the other hand, Baltimore has Edgar Allen Poe, H.L. Mencken, and the best crab cakes inside the Van Allen radiation belt. So, let’s not be too hard on Baltimore.

Baltimore also has Johnny Unitas, Cal Ripken, Jr., and, relevant for present purposes, Brooks Robinson—the three gods of Baltimore sports. Mess with any of these guy’s reputations and you will need to put on your boxing gloves.

Robinson is generally considered the greatest fielding third baseman of all time. Certainly, this opinion runs true in the Charm City. But it is wrong. Robinson was not even the best fielding third baseman of his generation.

By writing this, I understand that I will be chased out of every blue-collar bar in Baltimore. I will be chastised (even ridiculed) by close friends. I live in Maryland. This will be tough on me. But, as Ron Swoboda (a Baltimore native and graduate of Sparrows Point High School) once wrote: You can’t let political correctness stand in the way of the truth. So, here it is: For the years in which both players were in their primes (I choose 1960-1965), Clete Boyer was a better fielder than Brooks Robinson. Please take note of what I am saying. I am not saying that Boyer was a better overall player than Robinson. Certainly, Robinson produced much more offensively than did Boyer. Surely, Robinson had a longer career. Without doubt, Robinson is a Hall of Famer. Also without a doubt, Boyer is not. But for the years under consideration, Boyer was a better fielder.

To prove the point, we need to determine how to evaluate fielding prowess. The most common method is by fielding average. By this measure Robinson outranks Boyer. Robinson’s fielding averages for games at third base only (both players played a handful of games at other positions) were for the years under study .977, .972, .979, .976, .972, and .967. Except for 1965, Boyer’s were lower at .967, .967, .964, .954, .968, and .968. (Statistics are courtesy of baseballreference.com.)

However, fielding averages can be deceptive for two reasons. First, a fielding average depends on the official scorer’s determination of whether to score a play as a hit or an error. Prior to 1980, this function was often performed by beat writers in the home city. Only after 1980 did MLB appoint official scorers. So, the inherently subjective decision to score a hit or an error was compounded by official scorers, consciously or not, favoring the hometown heroes—those that they would need to interview and quote for stories the reporters wrote.

But there is another reason why fielding averages do not determine who is the better fielder. Take two fielders, Fielder A and Fielder B. Ten identical balls are hit to each. Fielder A reaches five, fielding each of them cleanly, and making five outs. The other five balls get past him for hits. Fielder B reaches all ten balls but makes an error on one, making nine outs. Who has the higher fielding average? Not the better fielder, I submit.

Fortunately, there is a wonderful statistic: range factor per game. This stat adds putouts and assists, that is, what you want your third baseman (or any other fielder) to do. Get to batted balls and make outs whether by catching fly balls or by fielding grounders and making the throws to the appropriate base, usually first base. This stat shows the true value of a fielder. Under this metric, for the years under consideration, Boyer is clearly the better fielder. As the following chart reveals, Boyer’s range factor per game was higher for every year except 1960.

Robinson Boyer

1960 3.28 3.24

1961 2.96 3.57

1962 3.10 3.71

1963 3.02 3.36

1964 2.94 3.22

1965 3.10 3.32

So, for example, Boyer’s range factor per game for 1961 and 1962 was .61 higher than Robinson’s. That means for every three games, Boyer gets to two balls and makes two more outs than does Robinson. Go figure how many wins that translates to.

But it gets better than that. As we all know, Boyer was a light hitter. He was often removed for a pinch hitter before the game’s conclusion. So, the more relevant statistic is range factor per nine innings played. Using that metric the difference between Boyer and Robinson is more pronounced. Consider the following chart:

Robinson Boyer

1960 3.32 3.69

1961 2.97 3.78

1962 3.13 3.76

1963 3.07 3.43

1964 2.97 3.31

1965 3.06 3.45

One thing should also be noted. The difference between Robinson’s range per game and his range per nine innings is much less than that of Boyer, reflecting the fact that Boyer was often removed for a pinch hitter. No surprise there.

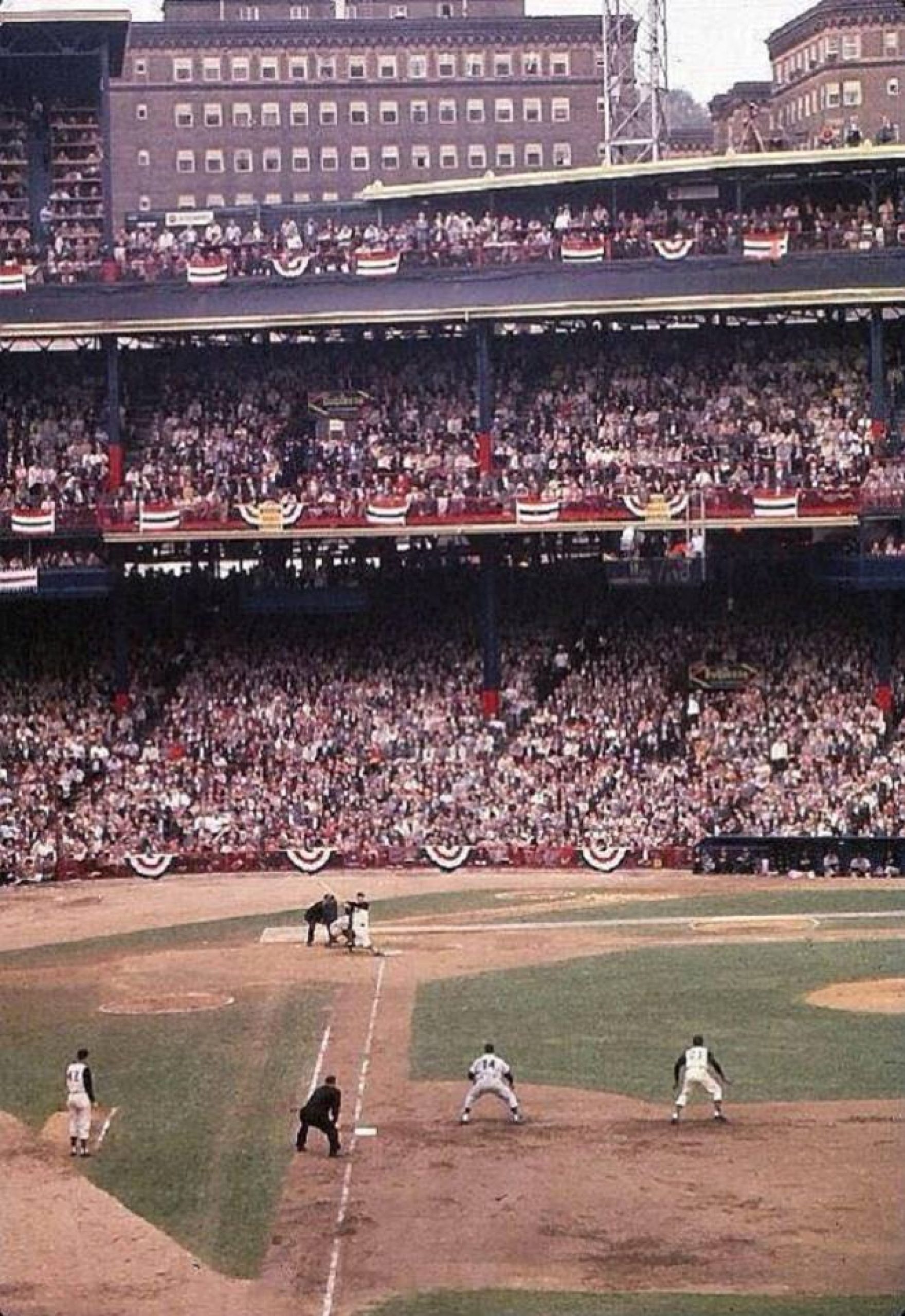

Boyer is clearly making more outs. In 1961 his range per nine innings is .81 higher than Robinson’s. That means every five games, Boyer makes four outs more than Robinson. And that is the average. Some games Boyer would make two or three outs that Robinson would not. That surely must mean that Boyer contributed to more of his team’s wins than Robinson. The difference for 1962 is .64. Every three games Boyer makes two plays that Robinson misses. Plus, Boyer’s numbers may be understated because of his home ballpark. Before the renovations in the 1970s, Yankee Stadium had a short right-field porch. Opposing teams would load up their lineups with left-handed batters in order to take advantage of the short right-field distances. The opposition’s left-handed batters would tend to hit the ball to the right side of the infield away from Boyer, giving him less opportunity to make putouts and assists. So, who’s the better fielder?

One more thing needs to be mentioned. I have pointed out the above-noted statistics to some fans of Robinson who retort with something like: “I don’t care what the numbers say. I saw Brooks Robinson play. He made plays no one else could make.” I saw Robinson play, too. I also saw Boyer play—scores maybe hundreds of times for both men, both in person and on TV. I was in Riverfront Stadium when Robinson made the play that makes all of the highlight reels of the 1970 World Series. He was playing relatively deep for hard-hitting Lee May, giving him more range. He was in fair territory when he caught the ball. His momentum carried him into foul ground. He bounced the throw to first. Nevertheless, it was an awesome play, one which will be remembered as long as baseball is played. But Boyer made similar plays. He also made more outs than Robinson. He was the better fielder at least during the years of the primes of both men. Robinson won the gold glove in each year, but he was not the better fielder.

While we are speaking of third basemen, why is Robinson’s and Boyer’s contemporary, Eddie Matthews, not mentioned among the greatest third basemen of all time? I may have a few thoughts on that.

Vince jankoski

Subscribe to our website, Baseball History Comes Alive with over 1400 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the one million hits mark with 1.052M hits and over 900 subscribers: https://wp.me/P7a04E-2he

Information: Excerpts edited from

Clete was good…BUT not in the class as Brooks!

Don’t forget Frank Malzone.

As a kid growing up watching baseball, I thought that Frank Malzone always was and would always be the 3rd baseman for the Red Sox. Three great fielding years, 1957-1959. Gold Glove winner each year.

Brooks was a magician at 3rd! He set the bar. This generations best is Nolan Arenado. Brooks has stated he is better than he was…tall praise. I watch Arenado and he is every bit the magician Brooks was!

Thanks for checking in Pat!

Saw both play but can’t say which one was better. Range factor may be deceiving as doesn’t it depend on how many balls are hit a thirdbaseman’s way? Darrel Evans, who was certainly not in Brooks or Clete’s class as a fielder is second all-time to Brooks in range factor for thirdbasemen 3.241 to 3.236.

That’s a good point Kevin. Maybe Vince will address that point.

Kevin,

You make an extremely valid and interesting point – a point so valid and interesting that I will stop what I am doing and respond. The only way that I can figure to truly determine how many balls were hit in the vicinity of a third baseman is to review the tapes of each game, something I am unwilling to do. Boyer played half his games in Yankee Stadium, a park which favored left handed batters. Opposing teams would tend to put more left handed batters in the lineup who would tend to hit the ball to the right side. This makes Boyer’s stats all the more remarkable. On the other hand, the Yankees would be more likely to start left handed pitchers in the Stadium which would tend to generate more opposing right handers. On the third hand, by 1960 pitching rotations were pretty much set and there wasn’t much platooning going on in any event. One way to answer your question in a rough sort of way is to calculate how many innings were pitched by left handed pitchers for both the Yanks and Orioles for the years at issue. However, to do that one would have to offset the number of innings pitched by the number of innings pitched by relief pitchers who would often be in the game after Boyer had been removed for a pinch hitter. The Yanks always seemed to have a good lefty in the bullpen – Luis Arroyo, Bud Daley, Marshall Bridges, Steve Hamilton. Both Arroyo and Daley pitched over 100 innings in relief in 1961 and 1962, respectively. Boyer was not playing 3rd (or anywhere else) during many of those innings. The only way I can explain Evans is that, while Robinson was playing 3rd base at age 40, Evans stopped being predominantly a 3rd baseman in his early 30’s. I am here to tell you that range deteriorates with age.

Kevin,

Upon further review, I have one additional comment: there is no reason to suspect that the number of balls hit to Boyer were appreciably greater in number than the number of balls hit to Robinson. Over a 6 year period one would expect things to even out.

Well written and researched, Vince. And for the years you picked there’s probably no statistical counter.

In fact, if you go by dWAR (based on Baseball Info Solutions’ defensive runs saved and Total Zone Rating by Sean Smith of BaseballProjection.com), Boyer buried Brooks in ’61 and ’62 with a dWAR of 3.4 and 3.2 respectively. Both best in the majors.

But if you go just a little beyond your range to 1967 and 1968, when both were still in their prime, a little over 30, Robinson posted an outrageous dWAR of 4.2 and 4.5, Boyer not close. For their yearly career average dWAR: Robinson 2.2, Boyer 2.0.

Just a little perspective. Like a politician, a baseball fan never met a statistic they didn’t like.

Best, Bill

Hi! Interesting article, but in 60 years as a baseball fan, I have never seen anyone who could touch Brooks as a fielder.

ButcI certainly agree that Eddie Matthew’s was one of the greatest ever. We should hear more sbout him. His was one of those who made the ‘ 57, ’58, and ‘ 59 Milwaukee Braves magic.

Thanks for checking in, Joe!

Joe,

Eddie Matthews coming up, God willing and the river don’t rise.

Brooks Robinson

“More” does not mean “”better.” Brooks all the way!

Joe Cunniff is alive and well! Tell him Budman said hello!

He’ll see this!

It seems important to note the comparison is only for the prime seasons of each career (1961-1965). The first reaction seems to be, “So what?”

So for a short time frame, Boyer was able to match – or exceed – Robinson’s level of play. Again, “So what?”

There are many ballplayers who flourished for short periods of time. They were good while they were good but none of them have come close to making the Hall of Fame, as should be.

Perhaps the biggest difference was Robinson’s tendency to make plays that were considered sensational, as compared to Boyer’s consistency in making difficult plays seem easy,

Because of that and the length of his career, Robinson got the attention and respect, deservedly so.

Brady Anderson once hit 50 homers in a season. “So what?”

George,

Certainly, Robinson was good for longer than Boyer. But 5 or 6 great years albeit only in the field is not chopped liver. Five great years gets some people into the Hall of Fame. See Sandy Koufax. Robinson is one of the rare people who got into the Hall of Fame based primarily on his glove. He is considered by many to be the greatest fielding third baseman of all time. Yet, for six years Boyer was consistently better. That is a fact worthy of recognition.

As for Brady Anderson, baseball if full of anomalies. Don Larsen was ten games below .500 for his career. Steve Stone won a Cy Young award. In 1961, Norm Cash hit 90 points above his career average. Go figure. That is why every spring hope springs eternal in the heart of every baseball fan.

Thanx for the comment.

Thanks for the great article, Vince.

I’ll comment on the topic from different perspective.

Growing up I was the ultimate Clete Boyer fan. Those of you who may gotten to read my book Mickey Mantle’s Last Home Run may think that I was a devoted Mickey Mantle, but truth be told, Cletis was my man. I still wear the number 6 jersey on my softball teams in honor of Clete and I’m north of 70 now. Of course, I always loved the Mick too, but when we were kids my older brother got first pick (on everything) and he chose the Mick as his favorite player. I had to try to assert my individuality so selected Cletis. I loved his name, and I loved the way he flashed the leather at third base. I spent many hours in our back yard trying to make diving stops just like Boyer. I even adopted his batting stance which got me in a bit of trouble since Cletis, as a lifetime .242 hitter, was not necessarily the guy to model at the plate. He pulled off the dish (stepped in the bucket) all the time so he could pummel lefties but he was toast for any righty who had a decent curveball. And I really couldn’t write a book Cletis Boyer’s Last Home Run, could I? No pazazz in that title nor any metaphoric significance.

As for the Clete versus Brooks comparison. I’ve been arguing for years that Clete was better than Brooks in the field. I admit I have a chip on my shoulder since Brooks always overshadowed Clete as a better player. Something I eventually came to drudging accept about the time I received my first social security check.

So, thank you Vince! Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! For your brilliant analysis in proving what I’ve been saying for decades. Clete was better than Brooks! (Fielding that is.)

I am much more of an Orioles fan than a Yankees fan.

And I was relatively young when I saw them both during the 1960-65 seasons.

But as youngster I always thought that Clete won the eye test.

Of course I saw many more Yankee games than Orioles games.

He was the first guy I can remember making lots of diving stops and throwing runners out from his knees.

I love Brooks, he’s the much better overall player, but Clete was at least his equal in the field for that time frame.

Just my opinion.

Interesting and well researched. How about after 1965? They were the same age (28) in ’65. Check games played. Robinson 1961-1964 played 163, 162, 161, 163 games per year. Boyer, 148, 158, 152, 147. That has to play some factor. Check Robinson’s stats after 1965. I believe his prime was then. I don’t believe anyone played the position as he from 66-71.

Vince,

Please know that I respect your opinion and research. I just disagree with the conclusion.

Koufax seems to be the only outlier concerning the length of careers for Hall of Famers.

Others who may be lacking significant seasons established themselves with long, consistent careers. That is actually the opposite of Koufax, who simply overwhelmingly dominated the seasons he was healthy. Thus, the exception.

Clete was a great fielder. But in their careers, Brooks Robinson was much better overall.

I was a yankee fan as a youngster. I was not an Oriole fan, but I did enjoy seeing Willie Miranda, Billy Gardner, George Kell, Bob Boyd, Bob Nieman, Tito Francona, Gus Triandos, Billy O’Dell, Joe Ginsberg and Billy Goodman. I don’t know why they didn’t do better. When Clete Boyer came along in a trade with Kansas City, I figured the Yankees knew something about him. Andy Carey was the third baseman in ’56 but he was eventually traded to KC when Clete Boyer came up. Clete was a fabulous defensive player. He even played some shortstop brilliantly for the Yankees in ’65 when injuries beset the defending American League champions. I really didn’t see Brooks Robinson very much, but what I saw was a man who could play as well as Boyer defensively and hit better than him. Boyer stood too far off the plate against lefties so they had the outside corner. If Robinson joined the Yankees, Boyer would be moved to short because he was a bit quicker and had better range. Nothing on the ground would have gotten between them.

That would have been great to have Brooks and Clete on the left side for the Yankees. You’re right, nothing would get through. In addition to having more range Clete had a better arm than Brooks. Brooks had quick hands and got rid of the ball fast but Clete’s arm was a rocket.