Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

THE BASEBALL HISTORY COMES ALIVE BLOG

Please note: As we compose new blog entries, we will now send each one out to all our subscribers as we post them. Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives -GL

September 20, 2022

Today I’ll continue with my weekly “deep dive” into the 1919 Black Sox scandal with a look at what admitted ringleader Chick Gandil confided to sportswriter Mel Durslag in a 1956 interview. This essay, along with all the others I’m posting in this series, is an edited version of the one that originally appeared in my 2019 book, Reflections on the 1919 Black Sox: Time To Take Another Look, available on Amazon. It’s a bit long, but if you’re interested in the Black Sox scandal, I think you’ll find it interesting.

Black Sox Ringleader Chick Gandil Tells His Side of the Story!

“I give you my solemn word I don’t know to this day what happened to the cash. I’ll go to my grave with a clear conscience.” –Chick Gandil to sportswriter Melvin Durslag

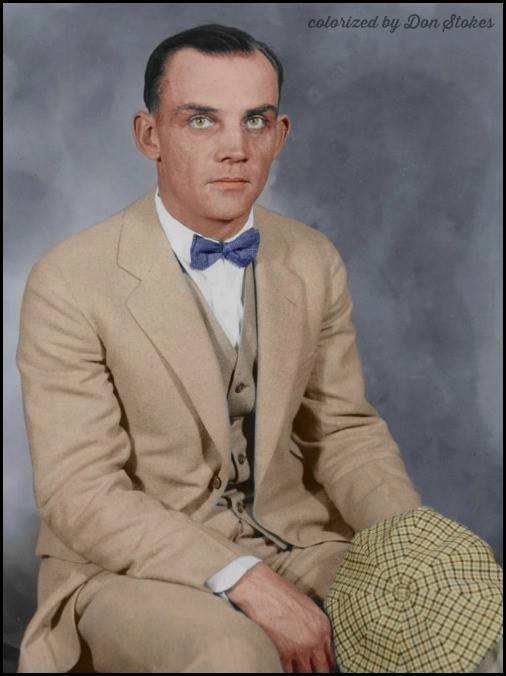

As the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Black Sox scandal approaches, I recently decided to reread the fascinating 1956 interview given by Chick Gandil to sportswriter Mel Durslag for Sports Illustrated. Gandil was often cast as the ring leader of the plot to throw the 1919 World Series. Thirty-seven years later, at age 69, he granted the interview “against the better judgment of my wife,” because, he said, there were things he wanted “on the record.”

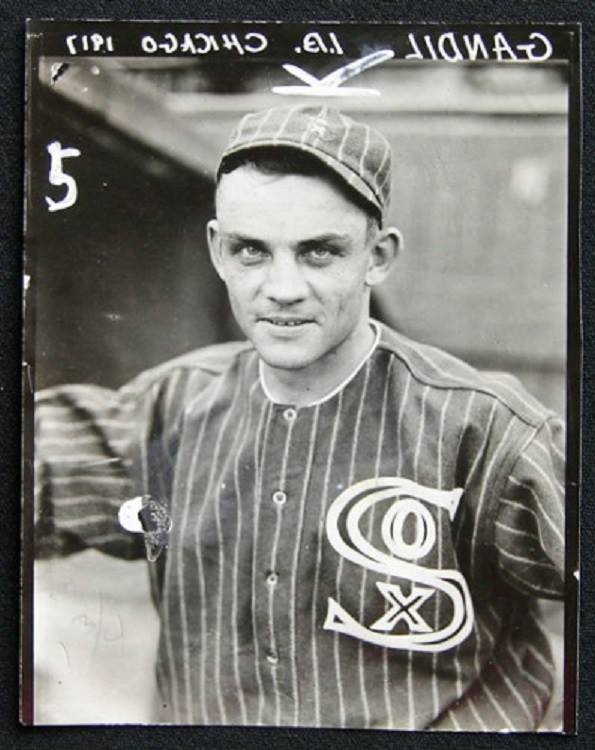

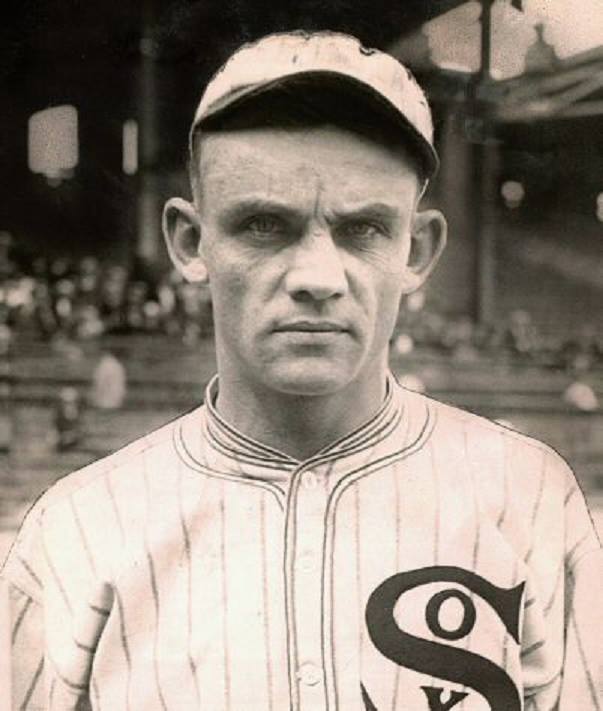

While we often hear cries calling for the reinstatement of Shoeless Joe Jackson or Buck Weaver, there has never been any love lost for Gandil. No one ever thinks he got a raw deal, only that he got what he deserved. Described by one contemporary as a “professional malcontent,” the physically imposing 6’2”,195 lb. Gandil had a callous disposition to go with a mean, bulldog mug that only a mother could love. In his early years, he acquired his imposing physical strength by working as a boilermaker in the copper mines and later became a heavyweight boxer. In short, he wasn’t the type of guy you wanted to mess with.

In speaking with Durslag, Gandil seemed to be at peace with himself over his role in the scandal that had rocked baseball to its very foundation. This was baseball’s darkest hour, and he had been at the center of the raging storm. Aside from embarrassment and personal qualms, he had never suffered any real hardship. Having worked for many years after his baseball career as a plumber, he noted that he and his wife “lived quietly away from the news.” Apparently, there were a still few details that he wanted to get off his chest.

What caught my attention in this interview was Gandil’s repeated insistence that the 1919 World Series was not thrown, and that all games were played “on the level.” Gandil never tried to whitewash or sugarcoat his involvement and made many striking admissions that had the effect of giving his claims a ring of truth.

In the interview, Gandil admitted to leading the plot and expressed guilt and remorse over having done so. However, he claimed that after an initial payment was made, the players panicked and ultimately tried their best to win. They concluded they could never get away with a fix, and instead decided to betray the gamblers. Carrying all this mental baggage into the series, according to Gandil, they couldn’t play their best and eventually lost.

A Litle Background

On February 25, 1917, Gandil was acquired by the White Sox. That season, the White Sox defeated the Giants in the World Series. In perhaps his first exposure to fixing games, Gandil and teammate Swede Risberg allegedly collected $45 from each member of the White Sox and paid off the Detroit Tigers in two crucial doubleheaders late in the season. The Tigers lost all four games, allowing the White Sox to win the American League pennant.

Then, as the 1919 World Series rolled around, the gamblers, including Sport Sullivan, knew Chick Gandil would be safe to approach with the idea of a fix. He described the scene:

I had only social contacts with gamblers until that September day in 1919 when Sullivan walked up to Eddie Cicotte and me as we left our hotel in Boston. I was kind of surprised when Sullivan suggested that we get a “syndicate” together of seven or eight players to throw the series to Cincinnati. The idea of a plot scared me, but he had a persuasive manner and backed it up with a lot of cash. He said he was willing to pay $10,000 each to all the players we brought in on the deal. Considering our skimpy salaries, $10,000 was quite a chunk, and he knew it. When I responded to him that we could never pull off a fix, he said, “Don’t be silly…it’s been pulled before and it can be again.”

The fix was on, and it was eventually agreed that “The Big Bankroll,” Arnold Rothstein, would pay out $100,000 to the players. The money was to be divided up among Gandil, Cicotte, and six other players of their choosing. They decided on Jackson, Weaver, Risberg, Felsch, McMullin, and Williams. They chose the teammates “to cut in on the gravy,” as Gandil put it, not because they loved them, but “let’s just say we disliked them the least.” The eight players then greedily schemed to get even more money by making another deal with a completely different group of gamblers. In addition to serving as the contact for the gamblers, Gandil was responsible for delivering the cash. He allegedly received $35,000 for his role in throwing the plot – nearly nine times his 1919 salary of $4,000.

Now it got interesting. “The heat was on,” said Gandil, as Game One of the World Series drew near. Rumors of a fix were rampant. Some players received threatening phone calls and others started to panic. Sport Sullivan heard rumors that the deal was off and confronted Gandil, advising him, “I wouldn’t call it the best policy to double-cross Rothstein.” Gandil continued:

“I truthfully wanted to go to our manager Kid Gleason and tell him the whole story, but I knew it wouldn’t be that simple. I realized that things were too involved by now to try to explain. I guess some of the others must have felt the same way, because the next morning I was called to a meeting of the eight players. Everyone was upset and there was a lot of disagreement. But it was finally decided that there was too much suspicion now to throw the games without getting caught. We weighed the risk of public disgrace and going to jail against taking our chances with the gamblers by crossing them up and keeping the ten grand…Our only course was to try to win, and we were certain that we could.” [Emphasis added]

The rest is familiar history. The heavily-favored White Sox lost the series and the eight conspirators were eventually indicted. In July 1921 they stood trial for fixing the series. The jury found them not guilty, but their joy was short-lived. Gandil and the others were permanently banned from organized baseball by new commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Although he believed Landis’ decision to ban them all was draconian, Gandil felt they deserved what they got. Once word got out that they had conspired with gamblers and had actually accepted money, they were forever guilty in the eyes of the baseball world, in spite of what may have actually transpired on the field.

Was Chick Gandil telling the truth? At this stage of his life, when setting the record straight seemed to be his objective, why would he continue to lie? Certainly the eight conspirators—with varying degrees of guilt and involvement—initially made a devil’s bargain with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series. At least some of them accepted money. Gandil admitted this. But in the next breath, he emphatically denied the games were thrown, an entirely different matter. Here are his words:

“Our losing to Cincinnati was an upset all right, but no more than Cleveland’s losing to the New York Giants by four straight in 1954. Mind you, I offer no defenses for the thing we conspired to do. It was inexcusable. But I maintain that our actual losing of the series was pure baseball fortune. I never did get any part of Rothstein’s $10,000 and I don’t know who did…I give you my solemn word I don’t know to this day what happened to the cash.” [Emphasis added]

These are strong words coming thirty-seven years after the fact. Is this the truthful confession of a man approaching the twilight of his life, wanting to set the record straight? Or is it the continuing distortions of a known liar and fixer, spinning yet another yarn? With a distance of ten decades, the issue can’t be resolved with certainty. Either Gandil was “lying through his teeth,” or history’s version of the 1919 World Series needs to be re-examined.

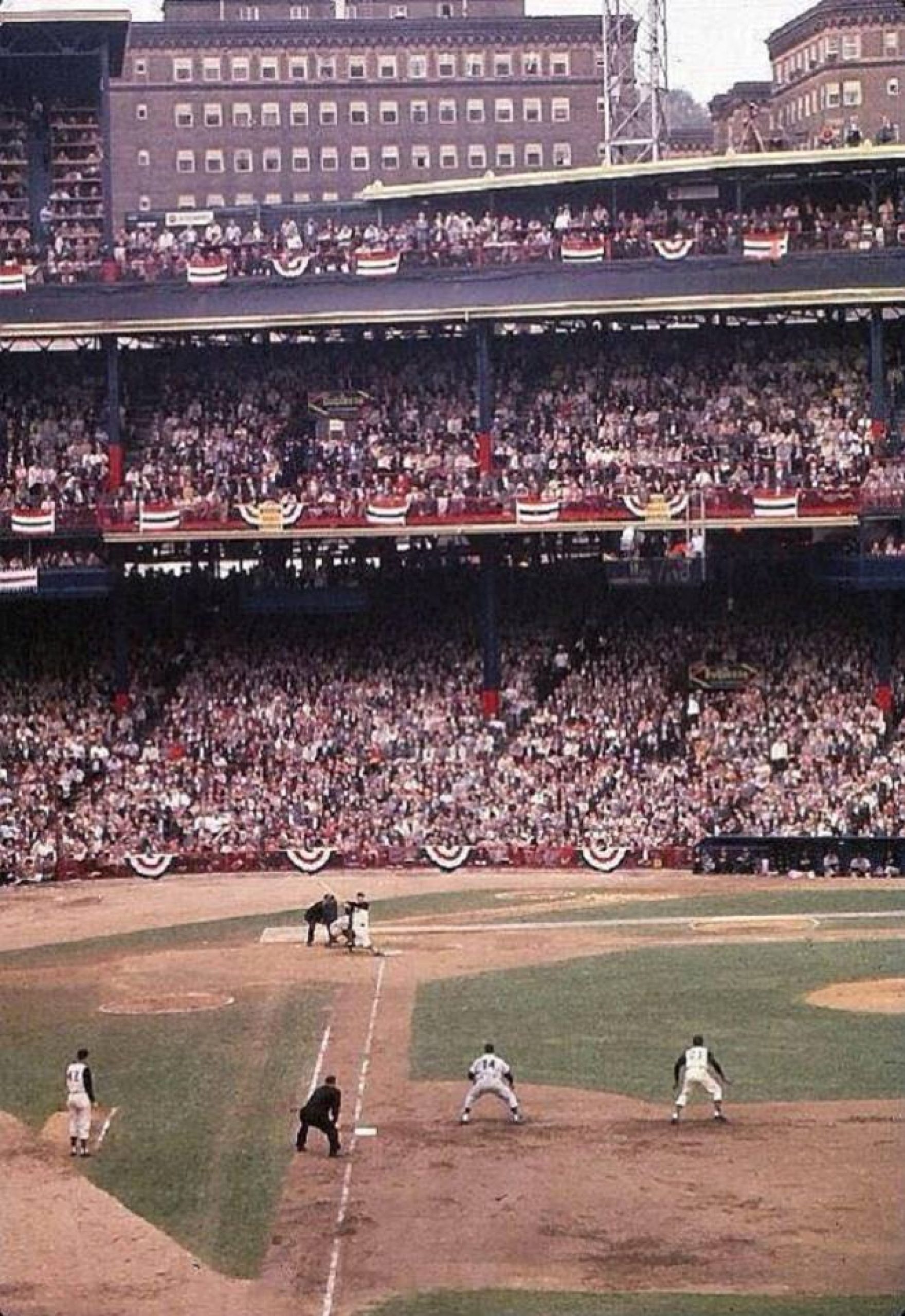

And what about their opponents, the Reds? They were surely a strong team, led by Hall-of-Famer Edd Roush and star players Heine Groh and Jake Daubert. They had deeper starting pitching, as Sox ace Red Faber was out. In a nine-game series, depth of pitching was key. And while they had deeper hitting, the White Sox were riddled with dissension and factions and entered the series with heavy mental baggage.

Writer Victor Luhrs made the interesting point speaking about White Sox ace Eddie Cicotte, saying that Cicotte played the series to win, but, suffering pangs of conscience, was in “bad mental shape as a result of his involvement with the gamblers. He was hardly fit to pitch the Opener.” Isn’t that exactly what Chick Gandil said in 1956?

One hundred years later, is it still necessary for us to blindly accept the conventional wisdom without questioning it? Is it possible that the Black Sox—while certainly guilty of conspiring with gamblers and taking dirty money—could have played most, if not all, of the games “on the level”? Why would Chick Gandil be lying at this stage of his life? No one can say for sure, but my hunch is that the conventional wisdom does not tell us the complete story.

This is not to exonerate the Black Sox by any means, but it’s merely a suggestion that we need to assess the proper levels of guilt. Conspiring with gamblers is less of an offense than actually throwing games. The prevailing version whitewashed the baseball establishment, which had turned a blind eye to the gambling scandal eating away at the game.

The Black Sox were an extraordinary mix of arrogance, stupidity, naivety, greed, and, yes, talent. Conspiring with gamblers to throw the World Series was a serious offense and they knew it. The acceptance of money irreversibly tarnished their reputations and made their future protestations of innocence ring hollow. As with a tar baby, once they touched the gamblers, they could never totally break free.

I contend it’s entirely plausible that as the start of the 1919 World Series approached, the thought of playing “crooked ball” was too much for at least some of them to mentally handle. Some may have cracked under the strain, as Gandil implied. The entire sordid episode was a blurred sequence of events where no one really knew what anyone else was doing. Conflicting stories were rampant.

It’s time to reexamine the events of the 1919 World Series with “pursuit of the truth” as the only goal. Let the chips fall where they may.

(Next up in this series: Eddie Cicotte’s performance in Game One. Stay tuned!)

Gary Livacari

As always, we enjoy reading your comments

Here’s a link to see the entire Blog Archives

Thoroughly enjoying this series, Gary. Younger fans need to know of the historical significance that the 1919 affair has, so your essays { AND the “Reflections” book} open up a huge avenue towards that. As for the pay-off, apparently Gandil thought he might find a little honesty in the gamblers, but to a crooked, career swindler and criminal, the words “integrity” and “honesty” don’t exist in their world. For the eight banned players, I guess the motto to their saga should be : “If you can’t dance to the music, don’t get on the floor”.

Thanks again, Tom…some great observatons!

I really enjoy reading this series. I look forward to seeing it in my in box.

I agree with you on this. I have thought for a while that, despite taking money, the players played to win. Their stats prove that. Jackson’s hitting, Weaver’s all around play, Gandil having a game winning hit, etc. As anyone that has played the game knows, it is almost impossible to turn it on and off whenever you feel like. Look at the 1988 World Series. Does anyone think the A’s weren’t trying their best? Eckersley? Accepting the gamblers’ money will forever doom the Black Sox but I don’t think the situation is as black and white as it’s made out to be.

Thanks a lot Phil…you’ve nailed my senrtiments exactly. I’m thrilled to find someone who’s on the samepage with me!

If you read my first essay in this series about the eye-witness acounts, you probably remember this statement by umpire Ernie Quigley, commenting about two great plays by Edd Rousch and Morrie Rath: “But for these two plays, the White Sox would have won two more games which would have meant the series for them.” I’ve always thought this was a very telling statement. Plus the Official Scorer (the Official Scorer for God’s sake!!) saw nothing suspicious the entire series! And I’m glad you mentioned the key hit by Gandil, which extended Game Six into extra innings (I think it was). All he had to do was strike out and the game was over. Instead he comes through with a key hit. That’s hardly what you’d expect to find from someone trying to “throw” the series.

Unfortunately, the book and movie, Eight Men Out, has given the general public an extremely superficial view of the scandal. Gene Carney once interviewed Eliot Asinof and got him to admit that he actually made up a lot of the information in the book. That’s hardly a ringing endorsement for the book considered the definitive account of the scandal. I know you agree with me that there’s a lot more to the story than we’ve been led to believe.

Next up in this series: Eddie Cicotte’s performance in Game One. Stay tuned!

Hello again Gary,

For reasons defying explanation I’m reading this great series in reverse sequence — but it hasn’t interfered one bit with my appreciation and enjoyment of your analysis. The “ring of truth”? I believe you have heard it, and recognize it for what it is.

For openers, you point out that many of Gandil’s after-the-fact statements are more likely true than not, considering how potentially damaging they were to his reputation, or what was left of it by then. (“Why would he say it, if it were not true?” is a natural, reasonable guide for one searching for the truth in such situations, and most legal scholars agree, going so far as to carve out an exception to the rule forbidding hearsay testimony if the statement a guy made tends to be self-injurious, as some of Gandil’s were.)

At the risk of putting too fine a technical point on the matter now, but as you also say — the fact that Gandil gave his interview 37 years after the Series and in the twilight of his life lends further credence to what he said in 1956. Nearly all courts today will allow testimony describing somebody’s “dying declaration,” for example, the idea being that when a guy says something about the circumstances of what he thinks is his own, impending death, he most likely is telling the truth. So a judge would admit evidence of that particular statement, even though nobody could hope to cross-examine it. WHY should we think he was telling the truth? Maybe he can already hear the fluttering wings of the dark angels, but in any case he knows his last breath isn’t so very far off. We trust that he was speaking the truth. Most folks would prefer not to take a dirt-nap with a lie on their lips, and by the mid-’50s Gandil was getting right up there.

Last, ’cause I’ve already said too much: If Eliot Asinof, who purported to be unraveling a longstanding historical mystery of grave proportions for the reader’s benefit, actually “made up a lot of the information” in Eight Men Out, then his work is worse than useless as a means of getting to the truth. Relying on his word, in that case, is a gamble no thinking person ought to take. Better to believe Chick Gandil, as you seem to be doing.

Congratulations on a very thoughtful and incisive series, Gary! Sorry to be so late in saying so.

Best regards,

Michael

Thanks so much Michael…you’ve as usual made some great points. So happy that you’re enjoying the series and have approached this topic with an open mind, which I think, is necessary if ever we’re to stumble upon the truth. My hope is that somehow this series of essays will open the minds of others.