Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Subscribe to Baseball History Comes Alive for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

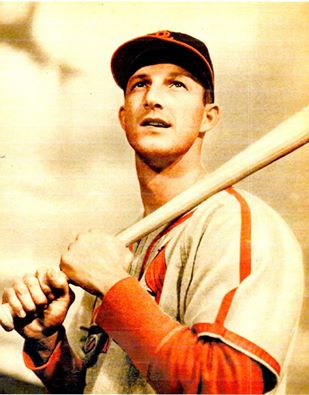

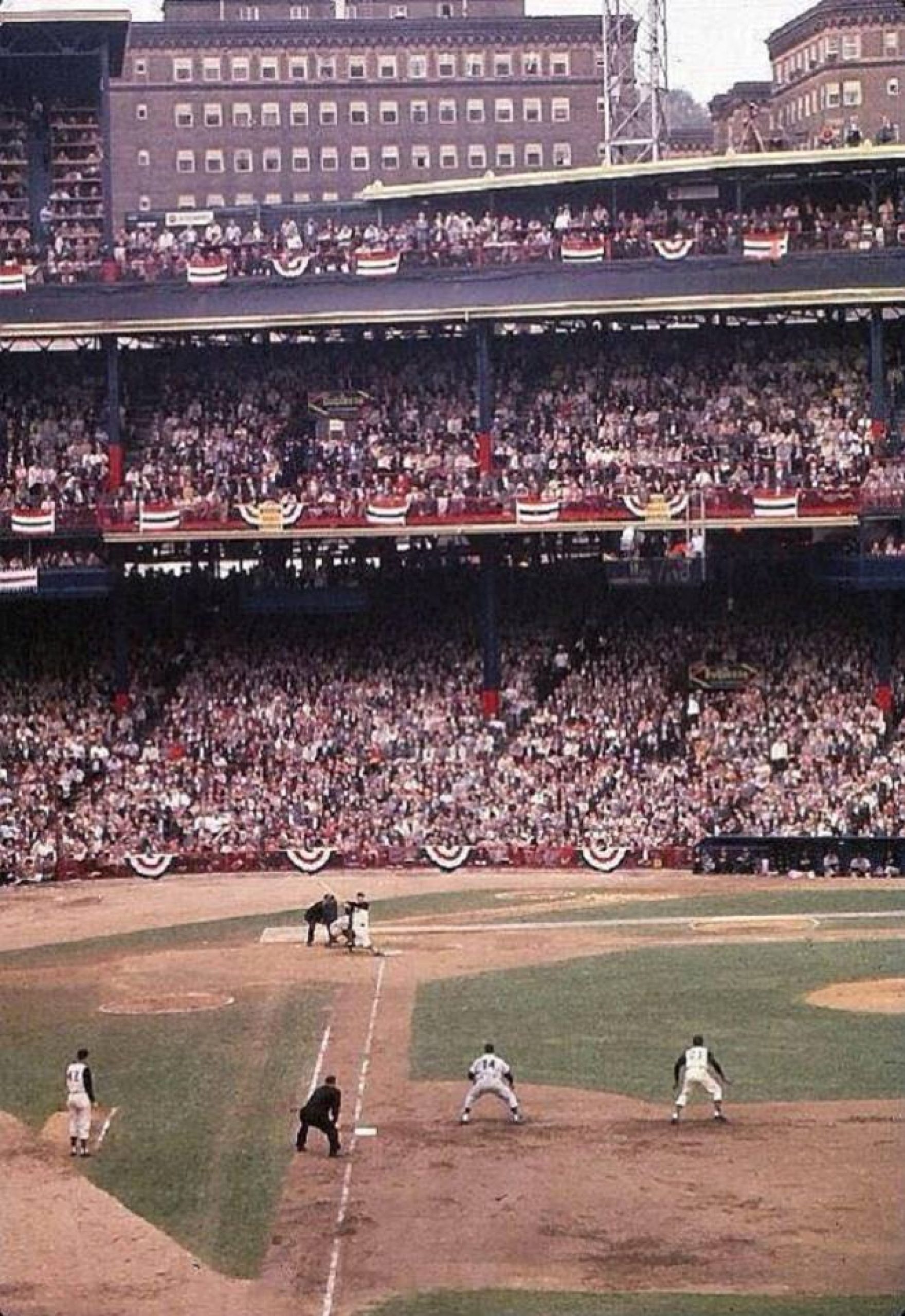

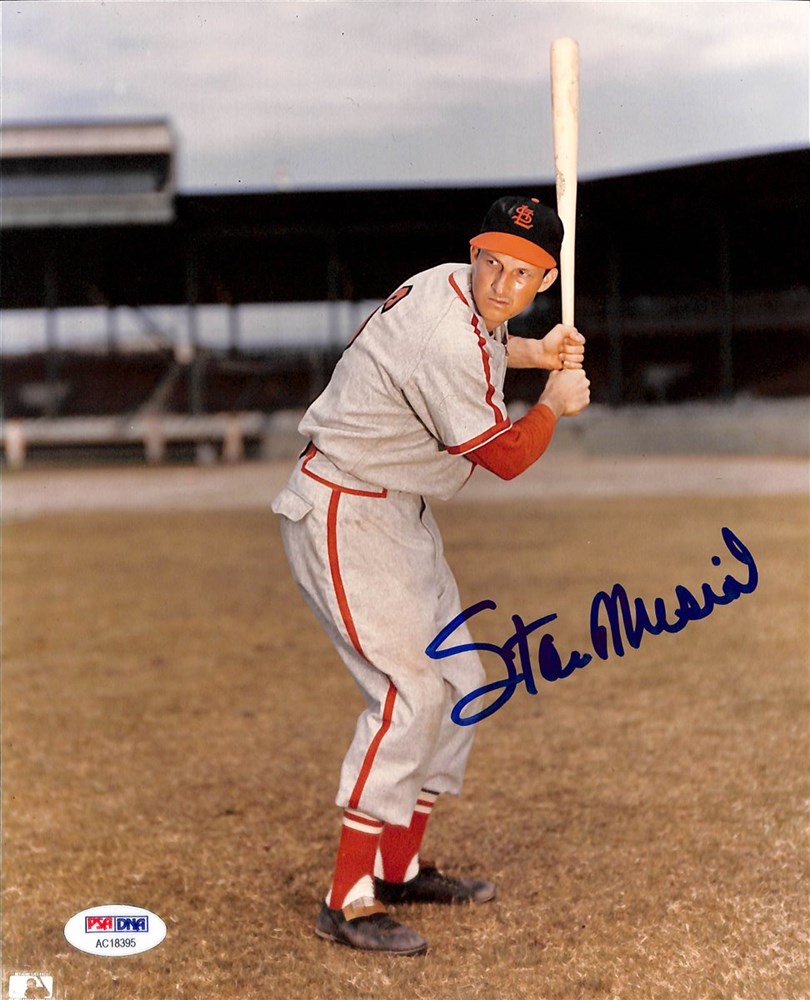

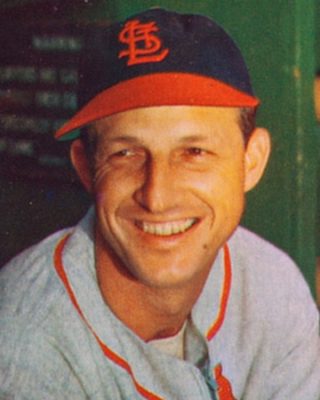

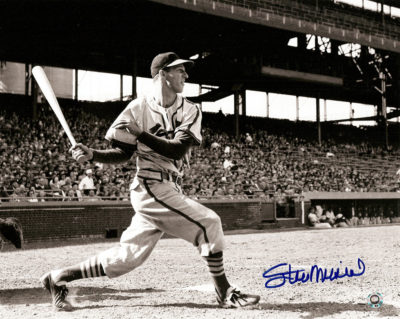

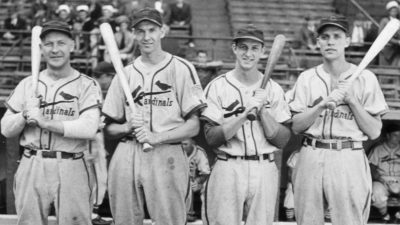

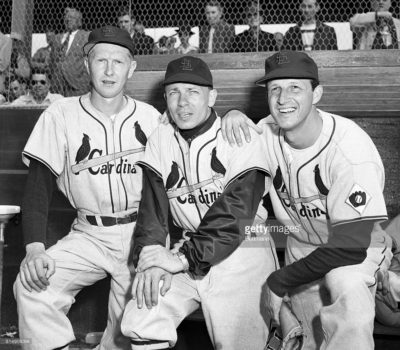

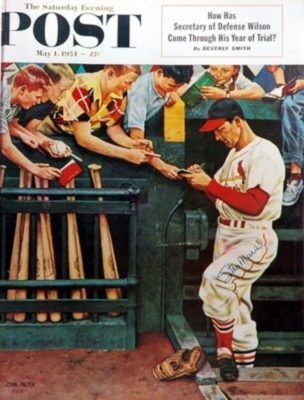

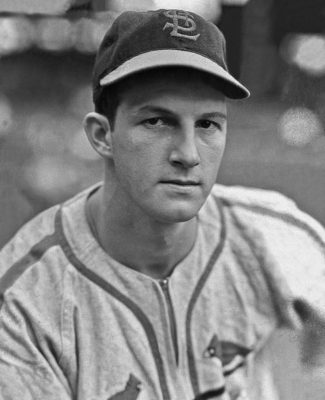

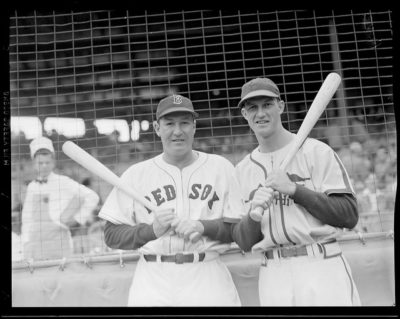

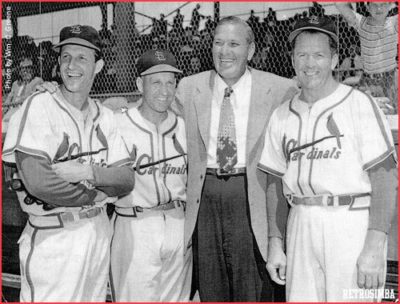

Stan “The Man” Musial Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

We welcome Paul Doyle back with an interesting essay depicting some of the labor issues that have confronted the game in the past, specifically, the 1951 salary “freeze.” As we learn, very little has changed…just the dollar amount of the contracts! The sums mentioned in Paul’s essay would be “tip money” for today’s overpriced and pampered multi-millionaire ballplayers. I think you’ll find interesting what Paul has to tell us. -GL

Stan Musial’s 1951 Salary Increase Blocked by Government

As we bid the year 2020 Adieu (and good riddance), we’ll probably look back on this year from a historical baseball perspective and marvel at all the changes that occurred.

A couple of German terms that I recently ran across apply to those of us who are baseball historians or, in my case, fans of baseball history. “Weltschmerz” is a word that translates to “nostalgia for a time we did not live in.” What better word to describe our passion for the game’s history than that?

“Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung” is also German which connotes “working off the past.” As Casey Stengel would have said, “You can look it up.” All our interests in the game are succinctly described by that unpronounceable term.

As Covid-19 spread its ugly virus across the world, we sat and watched as players and owners fought over commencing the season, including its length and salary structures. No fan base and a limited schedule meant that the virus had significantly reduced access to the game’s enormous pot of gold.

Baseball’s labor history is loaded with strife starting with the Player’s League of the 1890s. In the 1910s it moved into ongoing reserve clause issues and mortal threats from the Federal League; and it continued into more modern times with Curt Flood, Marvin Miller, strikes, lockouts, and free agency. However, one of the stranger stories from baseball’s past on a labor issue involved the federal government and a salary freeze in 1951. Ironically, it actually resulted in owners sticking up for higher salaries for the players on their own ballclubs!

We all look back to the year 1951 with fond baseball memories. It was the rookie years for both Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays. The Giants came back from a double-digit deficit to force the famous Bobby Thomson “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” playoff. But, in the real world, the country was already a year deep into another war, this time in Korea. Happy Chandler was unceremoniously dumped as commissioner in late July. Within a month, defenders of the faith were shocked that an owner (Bill Veeck) attempted to make a mockery of the game by sending – in what is now a politically incorrect term – a “midget” to pinch-hit for the St. Louis Browns.

Baseball’s salary freeze had its origins the previous September shortly after the start of the Korean War with the establishment of the Federal Salary Stabilization Board. Its purpose was to prevent the onset of runaway inflation. This new board was structured under the Defense Production Act of 1950. With salary control considered at the time a major component of economic stability, the board’s mission was to “freeze” salaries in order to temper wartime inflation.

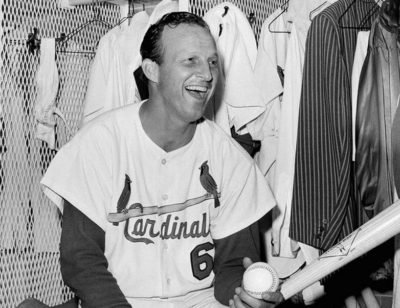

However, “freezing” was a relative term. Over the 1950-51 offseason, baseball owners had handled contract negotiation as they always had in the past. Star players held the most leverage in dealing with the usually pecuniary “Lords of Baseball.” In fact, in that offseason, many players received salary raises. George Kell went from $30,000 to $45,000, which, on its surface, appeared contrary to the intended “stabilization.” The St. Louis Cardinals signed star Stan Musial to a new contract that elevated his base salary from $50,000 to $80,000. For good measure, they threw in a $5,000 attendance bonus. Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams were still being paid their $100,000 contracts.

Most of these contracts raised no complaints from the Salary Stabilization Board. But there was an issue with the Musial deal. The board froze Stan’s salary increase and, for some reason, it became the focus of a board review of the contract. As is typical of government bureaucracies, the board expanded its reach over time and appointed new members to specifically address different industry “idiosyncrasies.” The arbitrary unfairness of how salaries were approved for baseball didn’t make much sense. Kell’s contract was approved because he was still making less than the Tigers’ best-paid player, Hal Newhouser, who was paid $50,000.

That summer the board added Democratic senator Harry Byrd and John Kieran, the erudite New York Times sportswriter writer, to the panel. Byrd solicited Hall-of-Famer Ty Cobb to be the third member. The concern was that professional athletes’ salaries might negatively affect the working public. When Cobb was hired, the board’s new mission became assessing and quantifying the sentiment arising from both the public and the athletes themselves.

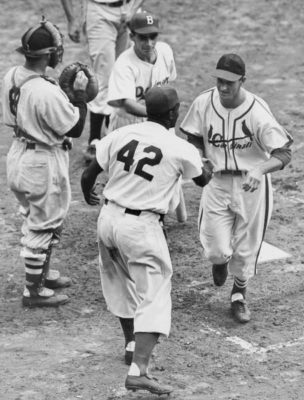

The panel’s fact-seeking mission extended into the 1951-52 offseason. Naturally, this meant that additional ballplayers might be affected when it came time for contract negotiations for the 1952 season. In fact, Musial’s contract was still frozen when the board issued other approvals on individual player salary increases, including $40,000 to Jackie Robinson. The board then decreed that clubs could give any salary to players, as long as the total salary structure didn’t exceed that of any year from 1946-50. However, logistics remained to be worked out on Musial’s contract. Then a month later, the Board retroactively approved the remainder of Stan’s 1951 salary.

With the Cold War in full fledge, the nation’s attention was on the ongoing Korean War stories. On the day that the board came out with its new arbitrary salary guidelines, the headline on the New York Times focused on hydrogen bomb experiments.

The rest is, as they say, history. Guidelines were established, but only short term. The board was disbanded after the end of the Korean War in 1953. Interestingly, Musial’s salary remained frozen until 1958 when he finally joined the $100,000 club. However, his pay increase lasted for only two years. After hitting just .255 in 1959, Musial signed a contract in 1960 with a 20% pay cut, back to $80,000.

Paul Doyle

Sources: NY Daily News-Aug 22, 1951; NY Times-January 17, 1952; NY Times-February 13, 1952; Wikipedia page on Salary Stabilization Board.

Subscribe to our website, “Baseball History Comes Alive!” with over 1100 fully categorized baseball essays and photo galleries, now surpassing the half-million hits mark at 546K hits: www.baseballhistorycomesalive.com

Enter our monthly Trivia Contest with A $50 Amazon Gift Card Grand Prize. Current topic: Baseball Hall of Fame

Check out our new Blog Page. Your comments welcome. Current Blog topic: Bring On a Knuckleballer.

Really nice piece, Paul, about something I knew nothing about. Interesting that they picked on Stan, one of baseball’s nicest guys, and tried to make him an example. Glad he finally got his money. Stan always earned every penny.

Thanks,Bill.

It’s amazing how you stumble across tidbits of history. I received a two day pass to Newspapers.com on Christmas.

I wanted to sample some papers on the date I was born. I was reading Duck Young’s column in the NY Daily News where he made a vague reference to it in his column.

Curious, I made inquiries into other newspapers in that time frame and filled in the blanks.

Things certainly were different back the, to say the least.