Baseball History Comes Alive Now Ranked #2 by Feedspot Among All Internet Baseball History Websites and Blogs!

Guest Submissions from Our Readers Always Welcome!

Subscribe to Old Baseball Photos and Essays for automatic updates (sign-up block found in right side-bar)

As a Free Bonus for subscribing, you’ll get instant access to my two Special Reports: Memorable World Series Moments and Gary’s Handy Dandy World Series Reference Guide!

Shoeless Joe Jackson Photo Gallery

Click on any image below to see photos in full size and to start Photo Gallery:

Shoeless Joe Jackson Sports bar, Rosemont, Illinois

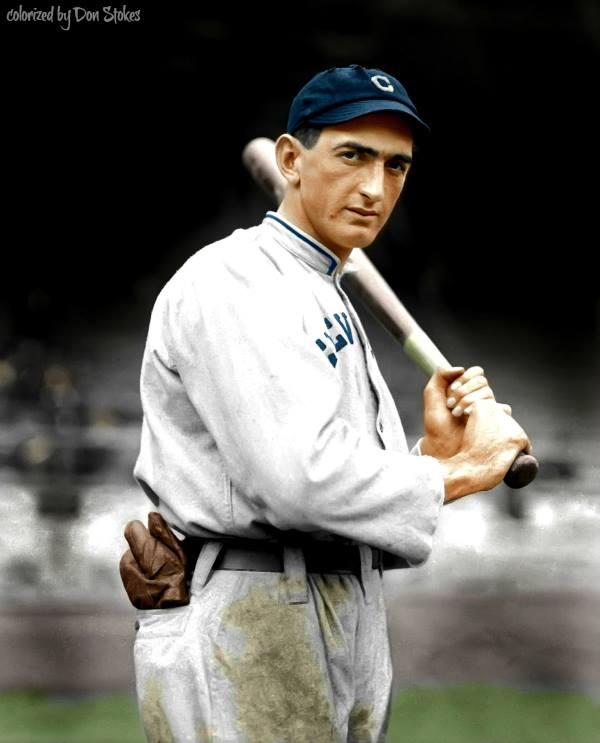

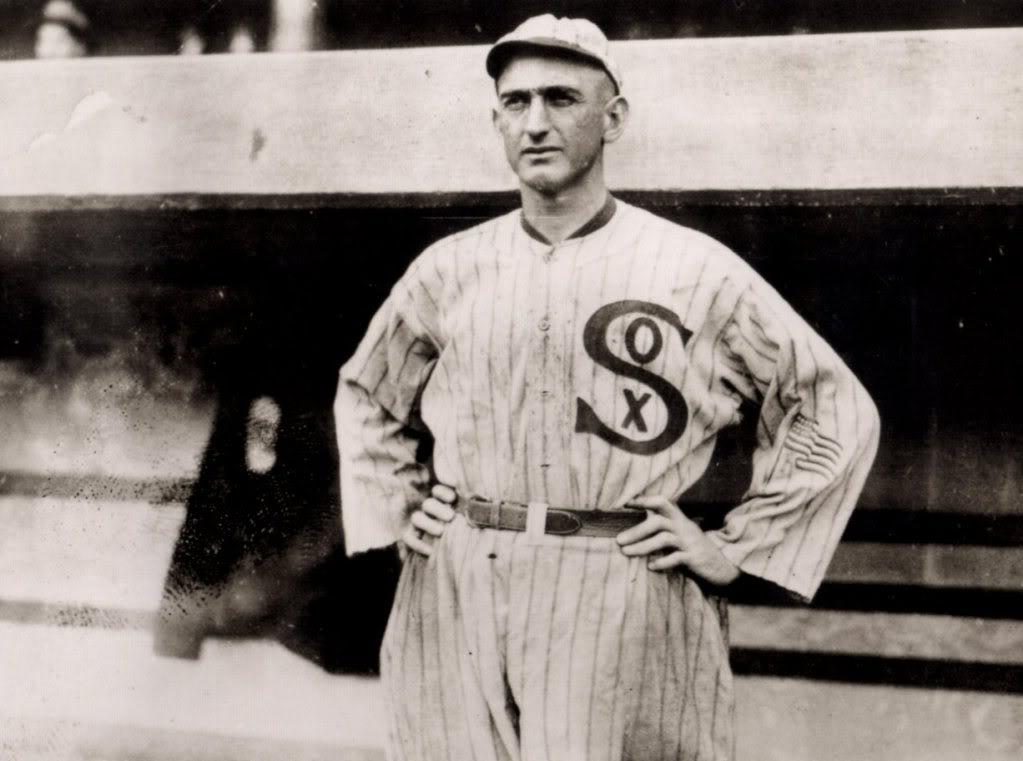

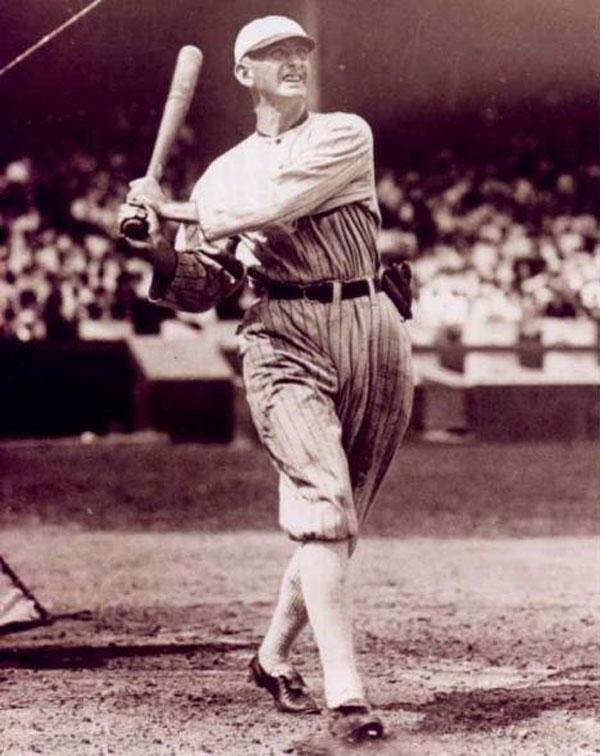

Shoeless Joe Jackson

Shoeless Joe Jackson

Joe Jackson burial site at Woodlawn Memorial Park, Greenville, South Carolina

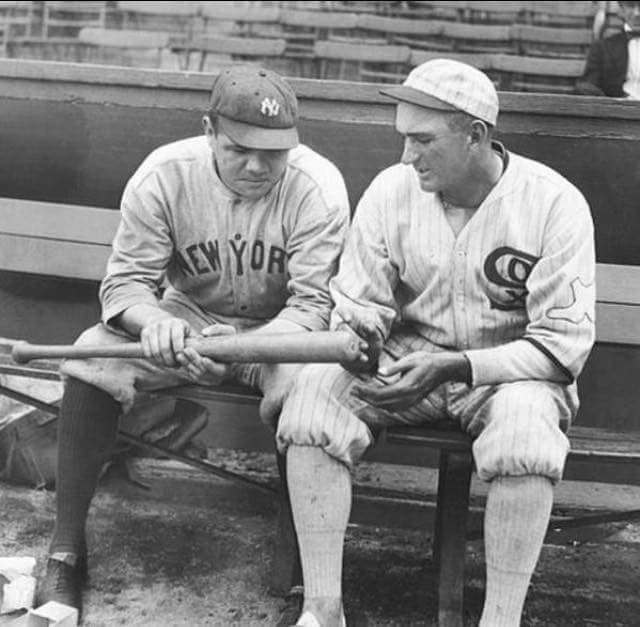

Baseball stars in 1920, Babe Ruth and Shoeless Joe Jackson

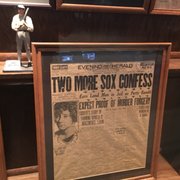

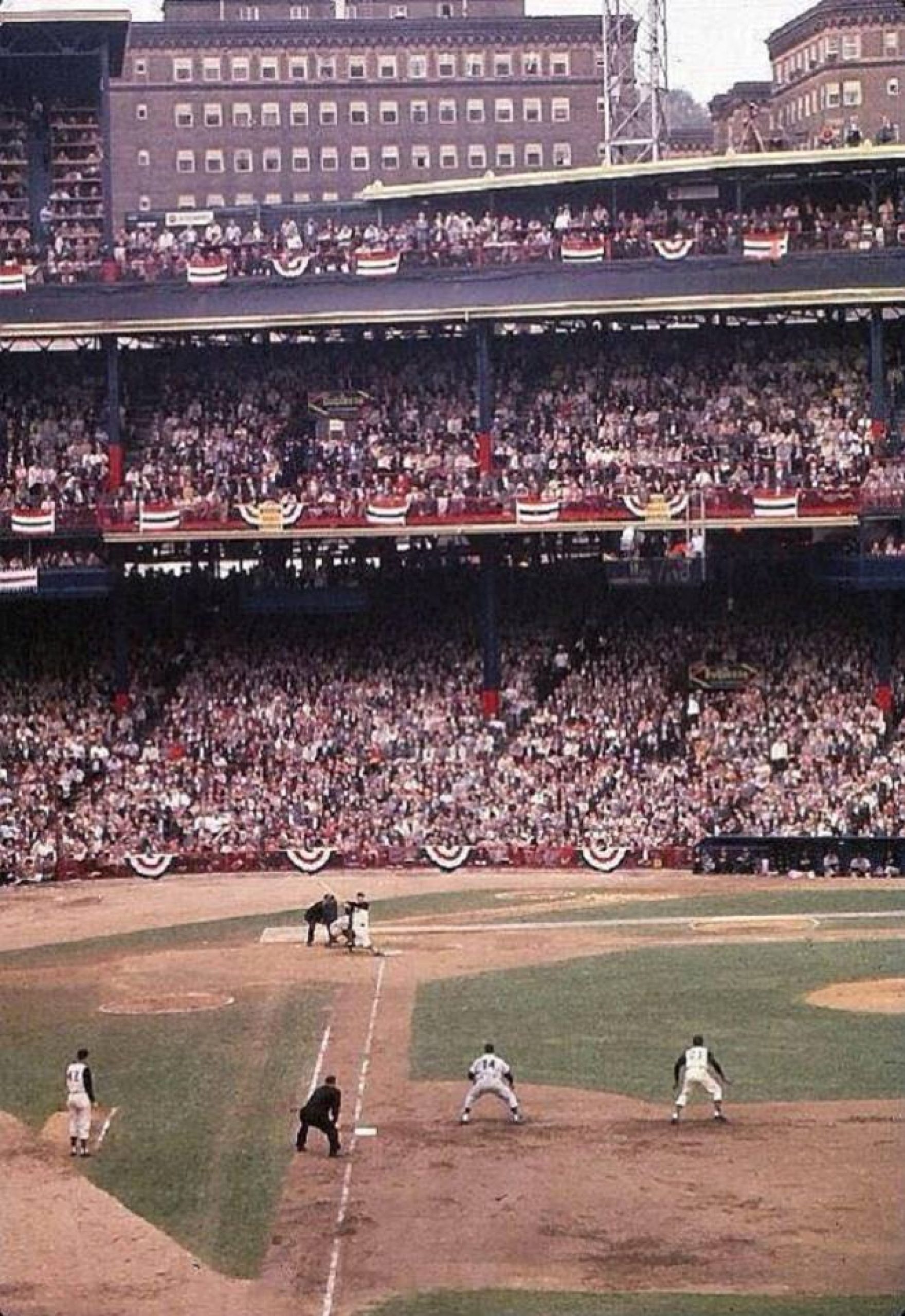

Black Sox in the court room

Joe Jackson’s bat, Black Betsy

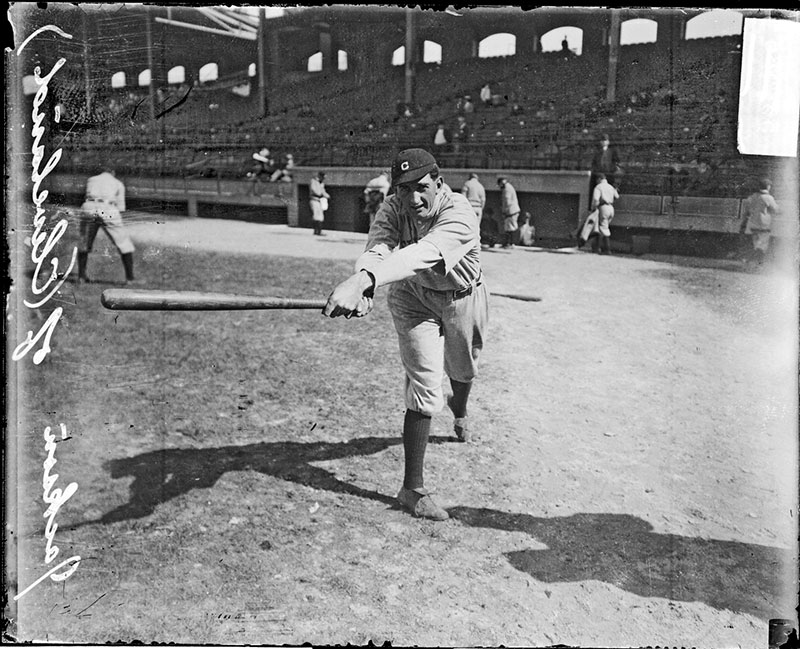

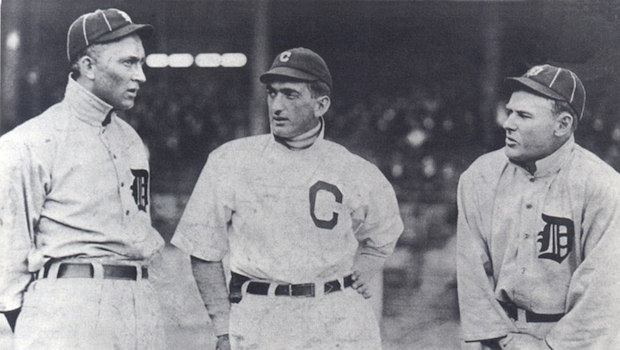

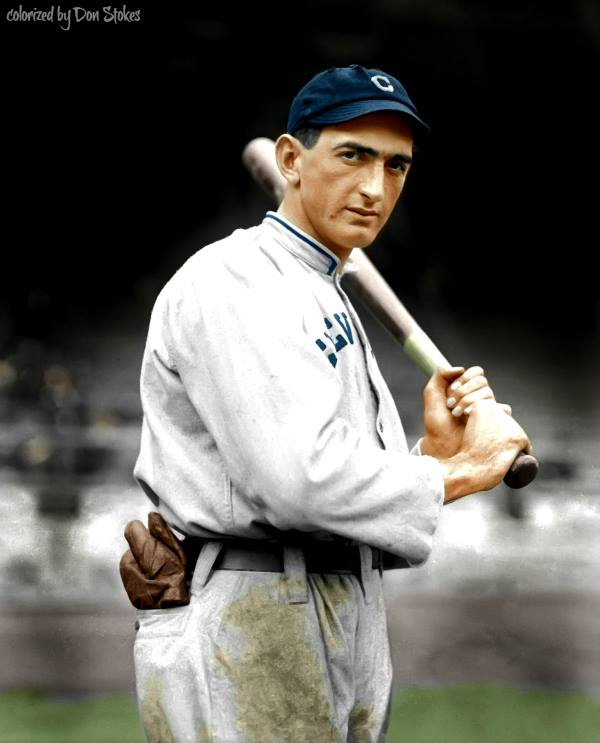

Jackson earlier in his career with Cleveland

Joe Jackson with interviewer Furman Bisher from the 1940s

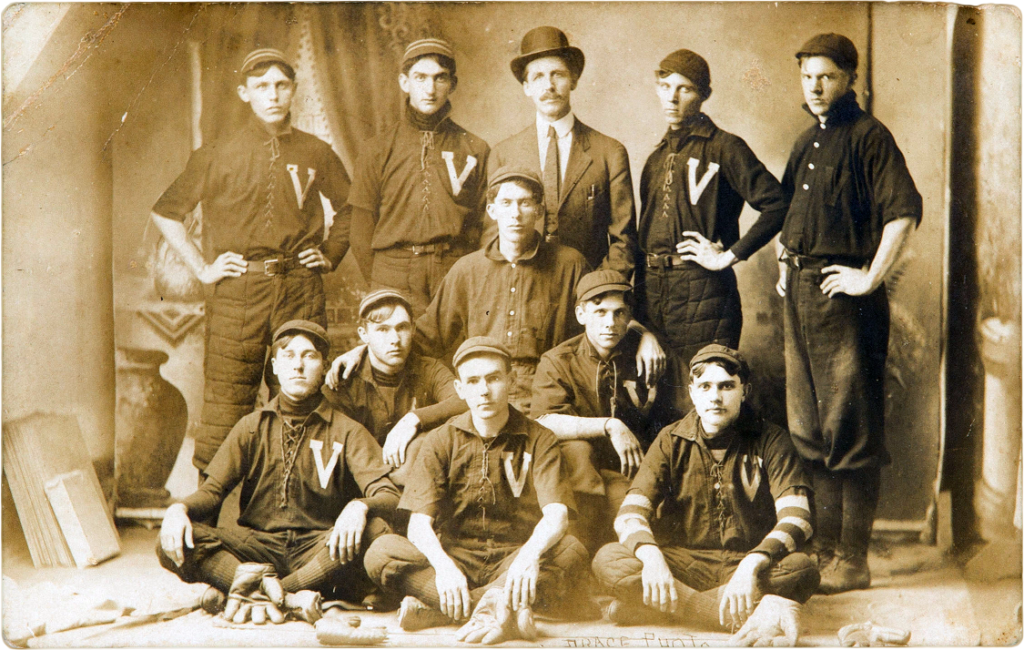

The 1907 Victor Mills team, . Jackson in top row, second from left. Was it while a member of this”mill team” that he got his famous “Shoeless Joe” nickname?

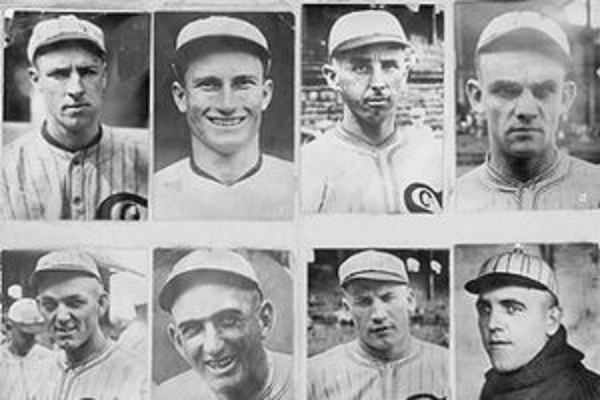

Members of the Black Sox Eight Men Out

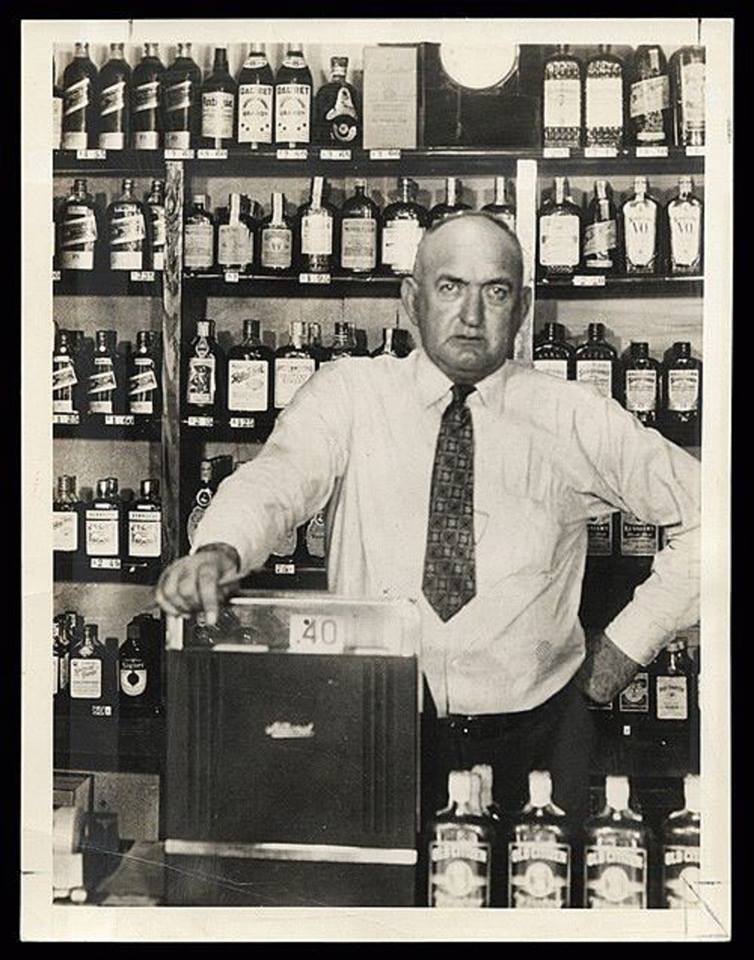

Joe Jackson later in life at his liquor store

Joe Jackson and wife Katie

Another Look At The 1919 World SeriesShoeless Joe Jackson, Part Two: Joe’s Play in the Field And At-Bat

“You know, he was such a remarkable hitter it was almost impossible for him to swing without meeting the ball solidly.” Teammate Dickie Kerr, speaking of Joe Jackson

Today, in another chapter in my on-going series of essays about the 1919 World Series, I’d like to address Shoeless Joe Jackson’s play and determine how it relates to his involvement (or non-involvement) in the scandal. As is well known, he hit a Series-leading .375 with six RBIs. He hit the only home run in the Series, and played errorless ball, handling 16 chances flawlessly and throwing a runner out at the plate.

In the featured photo below, we see a beautiful colorization of Shoeless Joe Jackson by our resident baseball artist, Don Stokes.

Criticism aimed at him usually runs something like this:

“In the first five games, he came to bat with eleven men on base and never drove in a run. In the last three games, when the fix was apparently off, he drove in six runs and hit the only Series home run. He didn’t hit in the clutch in the first five games.”

If you find that criticism valid, then you have to accept the assertion that ballplayers can “pick and choose” when they want to perform well. As baseball fans, we know that just isn’t so. Many great players have had less-than-stellar World Series performances, including Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Stan Musial and Gil Hodges. You could easily add more to the list. The World Series by nature is a pressure cooker played in the national stoplight. Many stars have struggled, while obscure players have often inexplicably emerged as heroes. That’s just baseball.

Keeping in mind the argument Jackson “let up” in the games that were tossed (supposedly the first two games), here’s how he did in Game Two:

He went 3-for-4, with a Texas leaguer behind second that he hustled into a double; a hard single to left; and a hard smash to right that the first baseman, Jake Daubert, knocked down, then threw late to pitcher Slim Sallee, with a hustling Jackson beating the play. Does that sound like he was “laying down” in a game he knew the White Sox were trying to throw?

Let’s also take a look at the play of two other stars and see if the same argument holds up against them: Player “A” went 2-for-18 (.111) in the first five games of the Series, failing to score or drive in a single run. But in the last three games, after the fix was supposedly off, he went 5-for-13 (.385), with two runs and an RBI. Player “B” went 2-for-15 (.133) in the first five games, but 4-for-13 (.308) with three runs, two doubles, and four RBI in the last three.

If you want to hold these players to the same standards some critics hold Joe Jackson, then perhaps we should examine the play of Eddie Collins (Player “A”) and Edd Roush (Player “B”). [this idea came from baseball researcher Bill Deane in e-mail exchange with Gene Carney]

As for his fielding, the criticism goes like this:

“Jackson was not charged with any errors in the Series, but he played out of position, he let balls fall in for hits, and three of the Reds’ triples went to left field where triples are rare.”

But in all the official accounts of the game, Jackson’s name is nowhere mentioned in any descriptions of the triples. Gene Carney asks: “Was he playing out of position, or was he playing where he should have been if the pitchers were trying for outs, and not tossing up hittable pitches?”

There’s no way to know for sure. But read this quote from Kid Gleason describing an incident in 1917 that surely would have held in 1919 when he was the manager:

“If there had been anything wrong, I would have known it. I knew everything that went on around the club.” It seems likely that Gleason would have spotted anyone playing out of position and moved them correctly. Would Gleason have just sat idly by and allowed Jackson to ‘play out of position’?

In addition, none of the ‘Seven Suspicious Plays’ spotted by sportswriter Hugh Fullerton, who was actively looking for anything out of the ordinary, involved Joe Jackson, either in the field, on the bases, or at the plate.

I think we can put the ‘he played out of position’ notion to rest.

For that matter, other than Fullerton, none of the reporters covering the Series for the Chicago and New York papers, as well as the wire services, wrote about any plays that looked suspicious. Even reporters who were pretty sure the fix was on could not be certain. Nor did the umpires or the Official Scorer observe anything untoward. Thousands of fans watched the 1919 World Series in person and saw nothing unusual. Why? As Gene Carney writes in Burying the Black Sox:

“Because that’s the nature of baseball. Players trying their best still make errors. The best hitters can strike out in the clutch, the best pitchers can lose their effectiveness and look awful for an inning or two. If you are convinced that the ‘fix is in’ you will find suspicious plays in any ballgame. If you are not on the lookout, you will not see anything except ‘baseball’.”

In summary, Joe Jackson’s play in the World Series was, on the surface, exceptional. He hit well against a staff rated better than that of the White Sox by Christy Mathewson. He hit safely in six of the eight games, with five multi-hit games. He fanned just twice in 32 trips to the plate and fielded 16 chances flawlessly. Again, quoting from Gene Carney:

“To suggest that he intentionally hit better in certain games than in others is to suggest that he could rack up hits at will, whenever he wanted, which is ridiculous. Batters can look awful in ‘Homerun Derby,’ when the pitchers are serving up whatever the batter wants. But even accomplished hitters make outs more often than they get hits, and often the outs come in the clutch.”

Sadly, all this does not make a definite case for Joe Jackson’s honest play. It’s just one way of looking at the facts. As with all aspects of the 1919 World Series, nothing is cut-and-dry; but at least on the surface, it’s very difficult to say that Joe Jackson did not play hard the entire Series: at bat, in the field, and on the bases; and that he played every game to win, as he maintained throughout the rest of his life.

Of course all this begs the question: If we are reasonably certain that Joe Jackson played hard and played to win the entire Series, does it really matter if he gave a contradictory statement to the grand jury, while under the influence of alcohol and after being coached by Comiskey lawyer, Alfred Austrian, and without benefit of personal legal counsel? A statement he later refuted? If he did accept money, does it really matter if, as he always maintained, he did nothing to earn it on the field?

It was a huge mistake for him to accept tainted money, making his later protestations of innocence much harder for even his supporters to swallow; but if someone wanted to give him money, did he really have a moral obligation not to accept it as long as he didn’t let it influence his actions? He also claimed he tried to inform Comiskey about it, and tried to give the money to either Secretary Harry Grabiner or Comiskey, but was rebuffed and told to keep it. When he testified to this in the 1924 Milwaukee trial in which he sued Comiskey for back pay, 11 of the 12 jurors believed his version of events rather than Charles Comiskey’s.

Could it be, as he and others have maintained, that the gamblers and the ringleaders wanted his name associated with the “fix” so as to give an air of credibility? In that sense, was it worth it to them to have Joe compromised by giving him money? This suggestion was given credence by Lefty Williams’ testimony in the 1924 Milwaukee trial when he said under oath that he “used Jackson’s name in the meetings with the gamblers [meetings Jackson did not attend] without Jackson’s knowledge or permission.”

Jackson also claimed Williams told him “he used my name in order to wring more money out of certain fellows supposed to be gamblers.” In other words, his name and his celebrity status as a star player might have been useful to the plot whether or not he was an active participant. The gamblers could spread the word that “Jackson’s in on it”; and, as a key player, that most certainly would have affected the odds.

I think these are all questions worth further investigation when considering Joe Jackson’s role in the 1919 World Series. Again, I don’t know what really happened. I just think, after the passage of 100 years, the whole sordid mess deserves a closer look; and that the conventional wisdom does not tell us the complete story.

As far as the money is concerned, I’ll have a lot more on that in my next essay. Stay tuned…

Gary Livacari

Photo Credits: All from Google search

Check out my two books, both now available on Amazon in e-book and paperback: “Paul Pryor in His Own Words: The Life and TImes of a 20-Year Major League Umpire”and “Memorable World Series Moments.” All profits go to the Illinois Veterans FoundationCheck out my book, “Memorable World Series Moments,” now available on Amazon in e-book and paperback. All profits go to the Illinois Veterans Foundation: https://www.amazon.com/Memorable-World-Moments-Garys-Reference-ebook/dp/B077L85D7C/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1547650967&sr=8-1&keywords=Memorable+World+Series+moments

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. Click here to view Amazon’s privacy policyhttps://www.facebook.com/Don-Stokes-Old-Time-Baseball-Colorizations-923346241033

Thank you for your fine work

Thanks for the kinds words, Jerry!